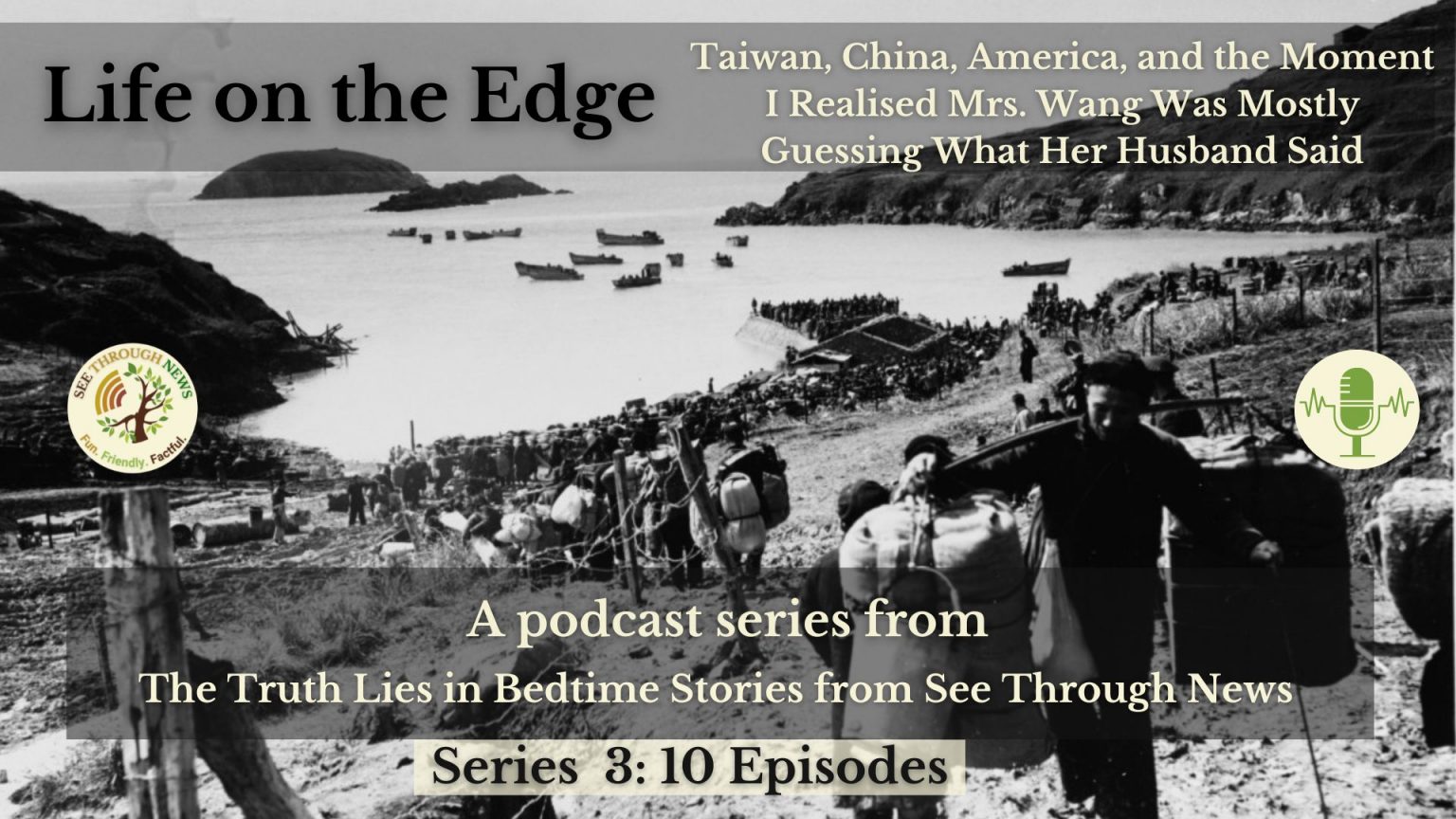

Episode 10 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News‘ podcast

In Episode 10, we learn what really happened.

What did you think? For a variety of perspectives, here are some reviews to discuss.

For best results, start at the beginning: Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition

Series 1: The Story of Ganbaatar – the only deep sea navigator in Mongolia

Series 2: Betrayed – a Tale of Christmas Spiritual Pollution

Coming Soon: Series 4 – The Quiet Revolutionary: the Heroic Role Played in a Plot to Assassinate the King by Someone You’ve All Heard Of.

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript

Episode 10: Return to Big Chen Island 2

Did you like that final scene, with the Three Brothers Wang toasting each other with home-distilled sorghum liquor, snacking on dried squid, and savouring duck-egg omelette, seasoned with nine-story-pagoda basil grown in Small Wang’s wooden wheelbarrow?

I was quite pleased with it too. It’s nice to tie everything up so neatly – it happens so rarely in real life.

Did you find it a little TOO neat and tidy?

OK – how about this then?

Big Wang did meet his youngest brother again, but not for long. By 1995, when Big Wang returned to Big Chen Island after 40 years as a soldier, Small Wang’s lungs were already failing.

Reunited at last, Big Wang made the most of the six months he was to have with his youngest brother. As Small Wang’s spirit ebbed away, their conversation took on an increasing urgency.

At first, they told each other about their Lives Apart. As Small Wang’s final, wheezing breath approached, and they reckoned their remaining time to be measured in weeks, and then days, the brothers started to reminisce about their Lives Together.

But by the time Small Wang breathed his last, and was buried in the garden in the wooden wheelbarrow as he’d wanted, all they talked about was their brother.

A decade later, when Middle Wang finally made it back to the island, Big Wang was in poor health himself. He’d lost the sight in his remaining eye, and now his mind was starting to fail him.

The group of Big Chen Island evacuees that Middle Wang arrived with, was not a typical tour group.

They roamed their former island home, from time to time knocking on the doors of places they once lived.

Startled homeowners would open the doors, open-mouthed as their predecessors from half a century before introduced themselves, before inviting them in.

You can imagine the surreal conversations that followed: comparing crop rotations, fishing grounds, and weather patterns, with someone whose house you’d arrived at to find ashes in the stove, a pile of wood for the next meal, a full store-room of rice, and unopened barrels of home-distilled sorghum liquor 50 years before.

Imagine the casually dropped references to stories of buried treasure. Think of those former occupants, trying to find a quiet moment on their own with no one looking. Or the new occupants discreetly keeping them in sight, just in case they revealed long-concealed hiding-places.

Middle Wang, however, did none of this. He spent all but one day of his two weeks on the island at Big Wang’s bedside.

Sometimes, Big Wang seemed aware of the miraculous reappearance of his other brother. He’d call him by his name, and keep asking where he’d been, and to promise he wouldn’t leave him.

At other times, Big Wang would re-live the day he’d left the island, telling Middle Wang about his plans to sell his cargo of dried squid, and pick up some extra cash doing deliveries for the traders of Fuzhou and Taizhou .

He could barely see with his good eye, but Big Wang insisted on keeping a black eye-patch over the eye he lost during his military service. When his mind took him back to sea, this lent Big Wang a piratical look.

More often, Big Wang was confused. He’d mistake Middle Wang for their younger brother, Small Wang, already a decade in his wheelbarrow coffin.

But mostly, Big Wang would look blankly at Middle Wang, like a stranger.

After 13 days of this, even the cheerful Middle Wang could stand it no more.

The day before he was scheduled to leave, Middle Wang embraced his unresponsive big brother, picked up his suitcase, and left Big Chen Island forever.

A month later, back in Alabama, Middle Wang heard Big Wang had died.

Within a year, he too was dead, but not before he’d told his story to me, with his wife translating, peering round my right ear, the same story I’ve just told to you.

Bit of a downer, right? Much less satisfactory than the first version, but maybe a bit more credible?

Still, at least Big Wang managed to see both his brothers before he died. A slender thread, but still a human link between the destinies of the Three Brothers Wang, before only one was left to tell me their unbelievable story.

Mind you, if you think that’s grim, I could kill all three of them off by 1956, if that would remove the sting.

It’s the hope that gets you, after all.

What if I were to tell you all three life stories are true, and I’ve simply connected them as pretend brothers, as a harmless narrative device?

How would that make you feel? Would it make the story better, or worse?

Would it make it more, or less likely, that you’d listen all the way to the end, as you now have?

Would it make it more, or less convincing?

What if only two of the stories were true, and I made one up just to make it sound better.

Or if only one’s true, and I made two of them up?

All storytellers can tell you about the power of the Rule of Three.

Ever wondered why we’re not told the tale of the Four Little Pigs, the Two Billy Goats Gruff, Goldilocks and the Eleven Bears, or the Six Musketeers?

But surely, even if the story of the Three Brothers Wang is a narrative confection – surely the bare bones of the story, the basic Cold War history of the evacuation – that must all be true, right?

I can’t possibly have made the entire thing up, from start to finish, can I?

You can’t really fact-check all the business about Mrs. Wang’s communication with her husband, the Alabama summer heat in her living room, and the biscuit tin with the letters.

But have you actually tried to find Big Chen Island on a map? ,

Have you checked the US Navy veteran online forums I mentioned?

Or the Professor’s article on the influence of Da Chen evacuees, published in the Journal of Culinary Historians of New York, if that exists?

It would only take a minute for you to check that. Go ahead – I’ll wait. [hold music]

Did you bother?

If not, you can’t really care all that much which bits are true, and which not, and that’s fine.

But if you do want to know which bits are true and which false, why?

Why does it matter so much to you?

If all I have to do is tell you something’s true and can be checked, and you don’t check it, it doesn’t actually have to be true at all.

At the end of each episode, I’ve been telling you that See Through News has a goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown By Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Taking action to remove carbon from the atmosphere depends on understanding climate science.

Science requires a belief in some kind of objective truth.

And that means knowing how to tell truth from lies.

When it comes to stories, we humans like things to be neat, simple and uncluttered by nuance or complexity.

So, next time you hear a story about climate action that’s neat, simple, and uncluttered by nuance or complexity – or in particular if you hear anyone say something like ‘I’d like to think’ or I’d like to believe’, or an answer seems to good to be true – remember this story of the Three Brothers Wang.