Episode 4 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News‘ podcast

In Episode 4, we learn of the unique role Small Wang played in his island community.

For best results, start at the beginning: Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 5 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Next, Episode 5: Wrong Time, Wrong Place

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript

Episode 4: The Wooden Wheelbarrow

By SternWriter

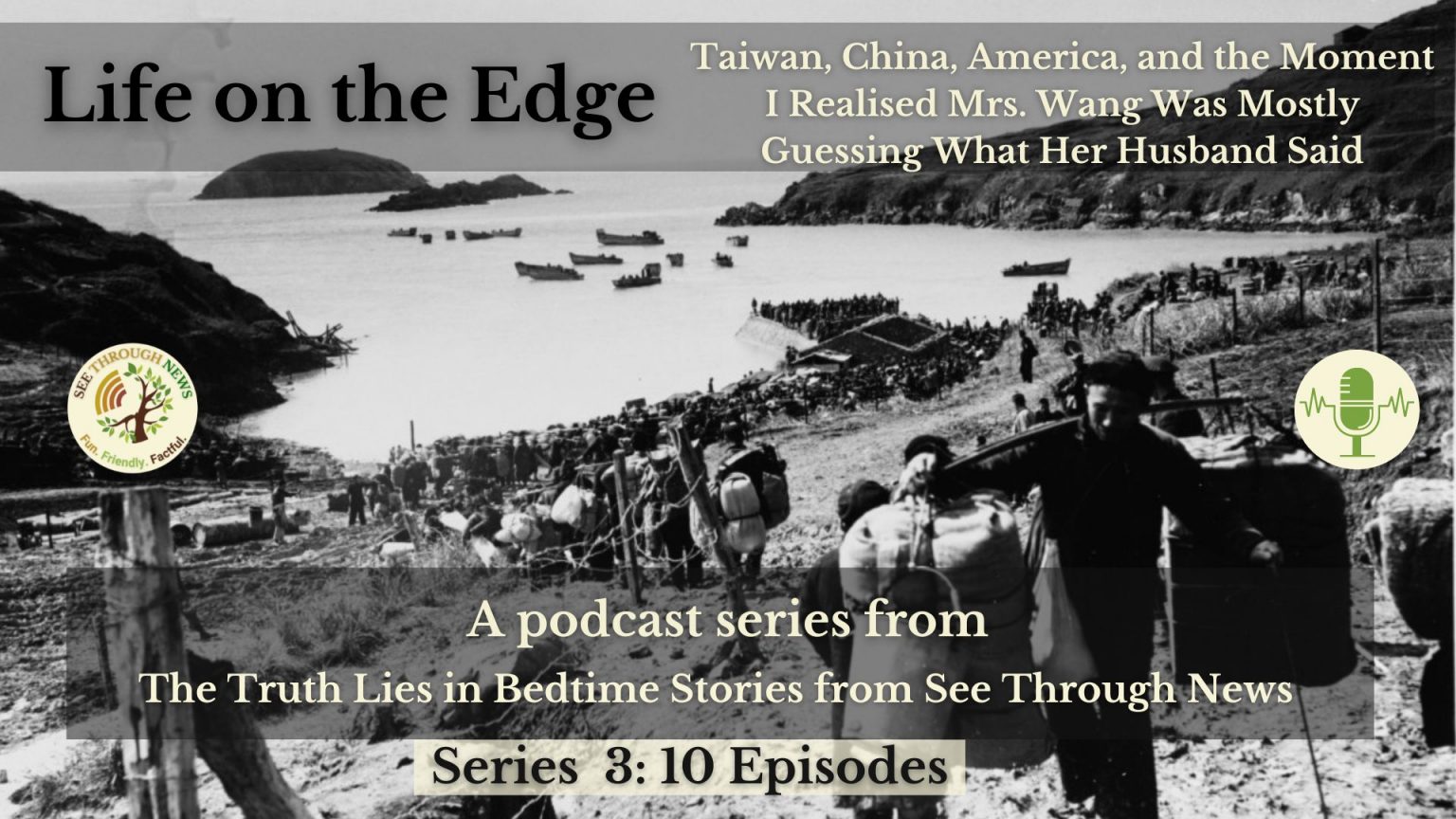

You can imagine the mayhem, the panic on Big Chen Island as February 10th 1955 dawned.

Instead of a few familiar fishing boats bobbing on the horizon, dozens of massive US Navy warships loomed.

The sky, until then the preserve of seabirds and songbirds, was now crisscrossed with aircraft from the Seventh Fleet. Their thrums, whops, and whooshes drowned out the birdsong, and everything else. Making yourself heard meant shouting into ears.

As he grabbed Small Wang’s wooden wheelbarrow, Middle Wang felt the vibrations and downdrafts from the fighters and choppers penetrating their kitchen’s thatched roof.

Breakfast forgotten, Middle Wang wheeled Small Wang through the kitchen doorway.

They reached the end of their garden path, and tried to join the throng of panicked islanders now jamming the route down to the beach. Below, dawn was revealing convoys of landing craft, already shuttling islanders from the beach to the waiting warships.

Beyond the American warships, tendrils of black smoke rose on the western horizon. The PRC fleet was steaming towards them, to liberate them with communism. As promised, right on schedule.

Theoretically, any of the islanders could have chosen to stay. I should explain why none did.

Ever since the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921, the Nationalists had been demonising them. The Nationalists recognized the threat posed by Mao Zedong and his peasant army. Soon, they were fighting the Communists for control of China, including deploying all the gruesome propaganda you might expect.

The war against the Japanese occupation had led to a temporary truce, but the moment Emperor Hirohito made his historic first broadcast, conceding unconditional surrender, the Nationalists demonisation of the Red Threat cranked up again in China.

As the Communists gained ground, and the corrupt Nationalist regime started to crumble, the anti-communist propaganda became increasingly hysterical and frenzied.

This narrative had of course eventually made its way even to such a remote backwater as Big Chen Island. The communist version of events never did.

So, for Small Wang, Middle Wang, and the other thousands of Big Chen Islanders, The Long March was a glorious rout of the enemy, not a fable of heroic survival. It was the evil Communists, not the corrupt Nationalists, who ate babies and tortured grandmothers.

Throw in mob instinct, and general panic, that’s why every single Big Chen Islander dropped everything when presented with this existential deadline.

As they headed for the waiting landing craft with only the clothes on their backs, they were all convinced that whatever fate awaited them, it would be better than life under Communism.

Landing craft by landing craft, Big Chen Island’s population moved from thatched cottages on land to open decks at sea.

Once aboard, they huddled wherever they could find space on the aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers and supply ships deployed to what the US Navy had dubbed ‘Operation Pullback’.

The islanders were dumbstruck, numb, in limbo. Their circumstances had changed so rapidly, and their futures were so uncertain, they were only living in the moment.

Their immediate concern was locating family members. If they didn’t live in the same cottage, if they hadn’t boarded the same landing craft, if they hadn’t ended up on the same ship, had they made it off the island?

If a child started to make reference to hiding things or burying things, parents quickly silenced them. No one knew how soon, if ever, they’d return to their ancestral homes, but it would be foolish to alert anyone else to the location of any last-minute hidden valuables.

These stories, and voices of the islanders, are hard to find. I’d not found any when I asked Mrs Wang to ask Mr. Wang if he’d mind me recording his life story.

I recorded Mr. Wang back in Alabama a year or two before he died, and he was one of the youngest to have a reliable memory of this event.

But let’s leave the islanders for a moment, and briefly consider Operation Pullback from the US Navy’s point of view.

If you’re interested in fact-checking this fictionalised true story, and sifting the truth from the lies, this is the best place to start.

The remarkable story of Big Chen Island is much better documented from the perspective of the US Navy than of the evacuees, but even so it’s quite obscure, even to keen military historians.

They tend to favour stories about fleets launched, battles fought, ships sunk, and sailors rescued. Dreadnoughts. Jutland. D-Day. The USS Indianapolis, as told by the shark hunter Quint in the movie Jaws.

Casualty-free civilian evacuations, on the other hand, are not staples of military history.

Still, for anyone interested in this sub-genre of naval mythology, there’s no more remarkable example than Operation Pullback.

At almost no notice, with almost no planning, 132 boats and 400 aircraft were deployed to evacuate 18,000 civilians in a matter of hours.

For details, check the internet. You’ll find facts about the 10,000 Nationalist soldiers, 4,000 guerrilla fighters and 40 thousand tons of military equipment that were also evacuated, but which I’ve not mentioned, until now.

This is my story, and it’s up to you to work out which bits are true, if you want to.

So there we go, there’s our nod to what was arguably the finest moment in the history of the US Navy Pacific Seventh Fleet. You’ll find answers about that elsewhere.

Here, though, is the only place you’ll get the answer to the question I asked Mrs. Wang to ask her husband, as the ceiling fan barely stirred the sultry summer air in that suburban Alabama living room. The Wheelbarrow Question.

How, I asked, amid all the chaos of that morning in 1955, with such steep, narrow, crowded paths leading down from their village, had Mr. Wang managed to get the wheelbarrow containing his paralysed little brother as far as the beach?

It took a while to extract, as explained in Part 1, but here’s his answer.

The path was so packed with escaping islanders, there was simply no room to squeeze the wheelbarrow into the crowd.

So Middle Wang and his younger brother, paralysed in his wheelbarrow, had to wait.

They grew increasingly desperate, as friends and neighbours shuffled past, clutching babies, holding infant hands, supporting elderly relatives, craning necks for the missing.

Of course everyone who passed by knew Small Wang, and immediately recognised his dilemma. But willing though they were, there was nothing they could do to create the space necessary to insert the wooden wheelbarrow.

Even if they had, the wheelbarrow would almost certainly be toppled in the melee, tipping paraplegic Small Wang down the steep slopes, helpless to break his fall.

So for hours, Middle Wang and Small Wang had to endure the helpless shrugs of their fellow islanders as they passed by, crammed together in their desperate escape to the landing craft on the beach. All the while, the plumes of smoke from the communist warships grew blacker and closer.

So it was that Middle Wang and Small Wang were last in the queue to leave Big Chen Island.

The number of evacuees usually quoted in the US naval histories is 18 thousand.

It must be an approximation, but if it’s accurate, Middle Wang was the 18,000th Big Chen Islander to be evacuated.

What about Small Wang? Was he the 17 thousand, nine-hundred and ninety-ninth?

Now we come to the first big twist in the stories of the Three Brothers Wang.

By the time Middle Wang, right at the back of the queue, had manoeuvred the wheelbarrow to the bottom of the path and onto the beach, there was no one else on the beach, and the last US sailor was in the process of boarding the last landing craft.

Had Big Wang been with them, the two elder brothers wouldn’t have needed to exchange so much as a world, even a glance. They would have executed their trademark Butt-Kissing Move, plunged through the surf, and had Small Wang on board in the same amount of time it would have taken them both to get there themselves.

But Big Wang wasn’t here this time, Small Wang was too heavy for Middle Wang to carry alone.

Middle Wang and Small Wang screamed to get the sailor’s attention, and when he turned round they saw the panic in his eyes.

They had no idea what he was shouting back at them in his strange language, but his gestures at the approaching communist warships, about to Liberate Big Chen Island on schedule, needed no interpreting.

Middle Wang, only 18 years old himself, looked at his 16-year-old brother. Small Wang, incapable of gesture but wise beyond his years, simply pursed his lips towards the departing landing craft, and nodded.

When the communist warships arrived, after Middle Wang had become the 18,000th and final islander to make it to a US Navy warship, they discovered only one living person left on Big Chen Island.

There, on the beach, with the smoke from the island’s abandoned breakfast stoves rising behind him, was Small Wang in his wooden wheelbarrow.

For nearly all of their short lives, the three Brothers Wang, had been inseparable.

None of them had known it at the time, but the moment Big Wang sailed for the mainland two months before, was the moment his destiny became irrevocably separated from those of his brothers.

This moment on the beach, when Small Wang, in his wooden wheelbarrow, watched Middle Wang, blinded by tears, splash through the surf to leap onto the last departing landing craft, was the moment their two paths diverged.

In Episode 5, Wrong Place, Wrong Time, we find out what happened to Big Wang