Episode 3, Series 3 of The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories podcast Life On The Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said

In Episode 3, we hear the turning point of this story, on Feb 10 1955, which dawned a day like any other…

For best results, start at the beginning:

Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 4 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Next, Episode 4: The Wooden Wheelbarrow

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript

Episode 3: A Morning of Comings and Goings

We already know for sure what two of the Three Brothers Wang were doing on the morning of February 10th 1955.

So far, we – and they – have no reason to doubt what the third was up to.

With dawn breaking, we left Small Wang in his wooden wheelbarrow, and Middle Wang, stoking the fire to boil the breakfast rice porridge, slicing bits of pickles, and chopping nine-story-pagoda basil.

Duck-egg omelette seasoned with nine-story-pagoda basil was Big Wang’s favourite breakfast dish.

Maybe they’d put a bowl out for him. Maybe this would be the day their big brother would return from his trip to the mainland.

It was at this moment that they heard the banging of pots and pans, and urgent shouts. They could make out one voice yelling in their local dialect. But someone else was shouting in a strange language that didn’t even sound Chinese.

Small Wang and Middle Wang shushed each other to try to make out what was being shouted.

Moments later, a neighbour, red-faced and panicked, burst through the door. He was followed by a foreigner.

Had Small Wang’s wheelbarrow been facing the door, he might have recognised the stranger was wearing a US Navy uniform.

Not speaking any English, Small Wang would have had no idea that the American sailor was yelling at them to drop everything and head for the beach, right now, and don’t take anything with you.

But there was no need, as their neighbour was yelling the same thing in their island dialect.

Let’s pause this scene for a moment.

Let’s leave the neighbour and the American sailor silhouetted in the kitchen doorway against the rising sun.

Let’s leave Middle Wang crouched, open-mouthed, by the fire. Let’s leave Small Wang, in his wooden wheelbarrow. for a moment more, as he searches his brother’s face for clues as to what was going on behind him.

Unless you’re an expert on post-Liberation cross-Straits history, or US Navy folklore, you’re probably ready for a bit of background.

Maybe you know all about Big Chen Island’s unfortunate location. You might be familiar with Chairman Mao’s mopping-up campaign following Liberation. You may already be up to speed on why Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, now hunkered down in Taiwan, was known to his American allies as Generalissimo Cash-My-Cheque.

If so, skip to the end of this episode.

The rest of you may recall from Episode 1 that Big Chen Island lies off the Chinese coast in the East China Sea.

What I’ve yet to mention, are the two critical facts that are about to change the lives of the Brothers Wang, and their 18 thousand fellow-islanders, forever.

The first concerns Big Chen Island’s geography. It’s around 400 kilometres due north of the northern tip of the island of Taiwan.

The second key fact concerns Big Chen Island’s history. When the 10th February 1955 dawned, it was still, nominally, ruled from Taiwan.

I say nominally because no one had ever really ruled this remote island community of fishers, farmers, smugglers and pirates.

Still, everywhere has to be part of somewhere else. For this island in the middle of nowhere, that somewhere else was, by default, whoever was in charge of China.

For the entire lives of the Brothers Wang, this had meant the Chinese Nationalists, lead by their warlord commander, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek.

But six years before, on October 1st 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong had stood at the Tiananmen Gate of Beijing’s Forbidden City, and announced to his peasant army the founding of The People’s Republic of China, or PRC.

This moment – known to the Communists as Liberation – marked the end of a bitter and bloody civil war between Chairman Mao’s Communists, and Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalists.

By Liberation Day China was on its knees. Before the civil war, it had endured 14 years of bitter and bloody Occupation by Japan. After atomic bombs detonated over Hiroshima and Nagasaki had seen the Japanese off, the Communists and Nationalists, who’d suspended their civil war to form a temporary anti-Japanese alliance, went back at each other’s throats.

The Communists, though outgunned, prevailed against the corrupt and weakened Nationalists.

Chiang Kai Shek and his Nationalists fled to what was then the remote island province of Taiwan. Initially, to re-group.

In Taiwan, the Nationalists declared the foundation of the Republic of China, or ROC, as a government-in-exile. They set about defending their crowded new home, vowing to re-take the mainland at the earliest opportunity.

This was only conceivable with American support, but the ROC’s prospects of taking mainland China back from the Communists receded with every passing year.

It wasn’t that Washington didn’t support them ideologically – this was the start of the Cold War, and anti-communist sentiment grew fiercer with every passing day.

Indeed, that’s why Washington sent American soldiers to a bitter and bloody civil war on China’s northern border in 1950.

Over the next three years America, supporting the anti-communist South Koreans, had 40,000 of its troops killed and another 100,000 injured.

Chairman Mao’s Communists, supporting the Communist North, were estimated to have had close to a million casualties. Despite all the bloodshed, neither side prevailed, and North and South Korea were created.

By 1953, Cold War stalemates were starting to look a lot more attractive than Hot war bloodbaths.

After that disastrous proxy war in Korea, Washington had no stomach to get bogged down in a direct military conflict between the Chinese Communists and Chinese Nationalists.

Thus, relations between the PRC and the ROC settled into a stalemate too.

America armed Taiwan defensively. US Navy Pacific Fleet warships patrolled the East China Sea. Washington supported the ROC diplomatically – and financially. It was around this time that bureaucrats in Washington started nicknaming Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, Generalissimo Cash My-Cheque.

Meanwhile, on the mainland, Chairman Mao had been securing the borders of the new PRC.

Mopping up various pockets of resistance and establishing China’s complex series of international borders was no simple task.

For a start, from Vietnam in the south to Korea in the north, China has more land borders than any other country in the world.

Then, in the post-war realignment, new neighbours kept appearing.

India became independent, Pakistan was born, increasingly fractious relations with communist big brother the Soviet Union required the creation of a string of buffer states…

Well… all this explains why life went on pretty much as usual on Big Chen Island for six years after Liberation in 1949.

Backwater status had given The Brothers Wang’s island home a charmed life. But by February 10th 1955, that life was hanging by a thread.

Over the previous few weeks, unbeknownst to its inhabitants, Big Chen Island had become the focus of an increasingly high-profile diplomatic and military tug-of-war.

With China’s land borders now secure, Chairman Mao finally turned his attention to the East China Sea. He issued an ultimatum, informing the world that the PRC’s navy would ‘liberate’ Big Chen Island on February 10th 1955.

In Taiwan, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, responded with tremendously patriotic speeches. Smiting his bemedalled chest, the Nationalist leader swore to defend the islands to the last drop of blood against the evil communist hooligans, etc etc.

This kind of rhetoric goes down well in certain circles, but those circles tend not to include the circles whose blood will be spilt to the last drop. Nor those circles who’ll have to clear up the mess afterwards.

Everyone – Washington, Beijing and Taipei – knew Big Chen Island was indefensible, and that the islanders were doomed.

Taiwan had spent the last 6 years fortifying and defending their own mini-buffer zones, two tiny series of islets, called Jinmen and Matsu.

These island groups were 100 kilometres from Taiwan, but within sight of the mainland coast.

By 1955, Jinmen and Matsu were fully militarised. They bristled with anti-tank defences, bunkers, anti-aircraft gun batteries. Artillery returned fire from regular bombardment from the mainland.Jinmen and Matsu were only retained at a massive financial, military and diplomatic cost that continues to this day.

America was prepared to pay these costs for Jinmen and Matsu, but the notion they’d do the same for Big Chen Island, 400 kilometres away, was ludicrous.

The communist occupation of Big Chen Island was inevitable. By 1955 Chairman Mao, Chiang Kai-Shek, and the US Pacific Fleet Command were all plotting what to do when it happened.

Chairman Mao simply announced the Chinese navy would be liberating the islands on February 10th 1955.

The US navy recommended a diplomatic retreat, and offered to evacuate the inhabitants to Taiwan.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek issued his stirring call to arms, urging the few thousand fishermen of Da Chen Island to patriotically resist the warships of the PRC navy.

The days leading up to this deadline had involved increasingly desperate diplomatic manoeuvres involving Washington, Taiwan, the US Navy and the United Nations.

As it became clear the Generalissimo wasn’t bluffing, and was prepared to sacrifice the 18 thousand islanders, including the three Brothers Wang, these diplomatic manoeuvres reached fever-pitch.

With the clock ticking, was there time for a last-ditch plan that wouldn’t involve the spilling of blood, gloriously patriotic or not?

Throughout this, the islanders, with no radio mast or receiver, were entirely oblivious to the urgency of their predicament.

Their local source of news was, after all, 16-year old Small Wang in his wooden wheelbarrow. He gleaned what he could from boats arriving from the mainland, but events were unfolding much too rapidly to rely on this method of communication.

Big Chen Islanders had long been aware of their precarious status, of course, but their relaxed attitude was understandable.

Distant governments had been bickering over who ruled them for as long as anyone could remember. In the meantime, those fish weren’t going to catch themselves, so it had been business as usual.

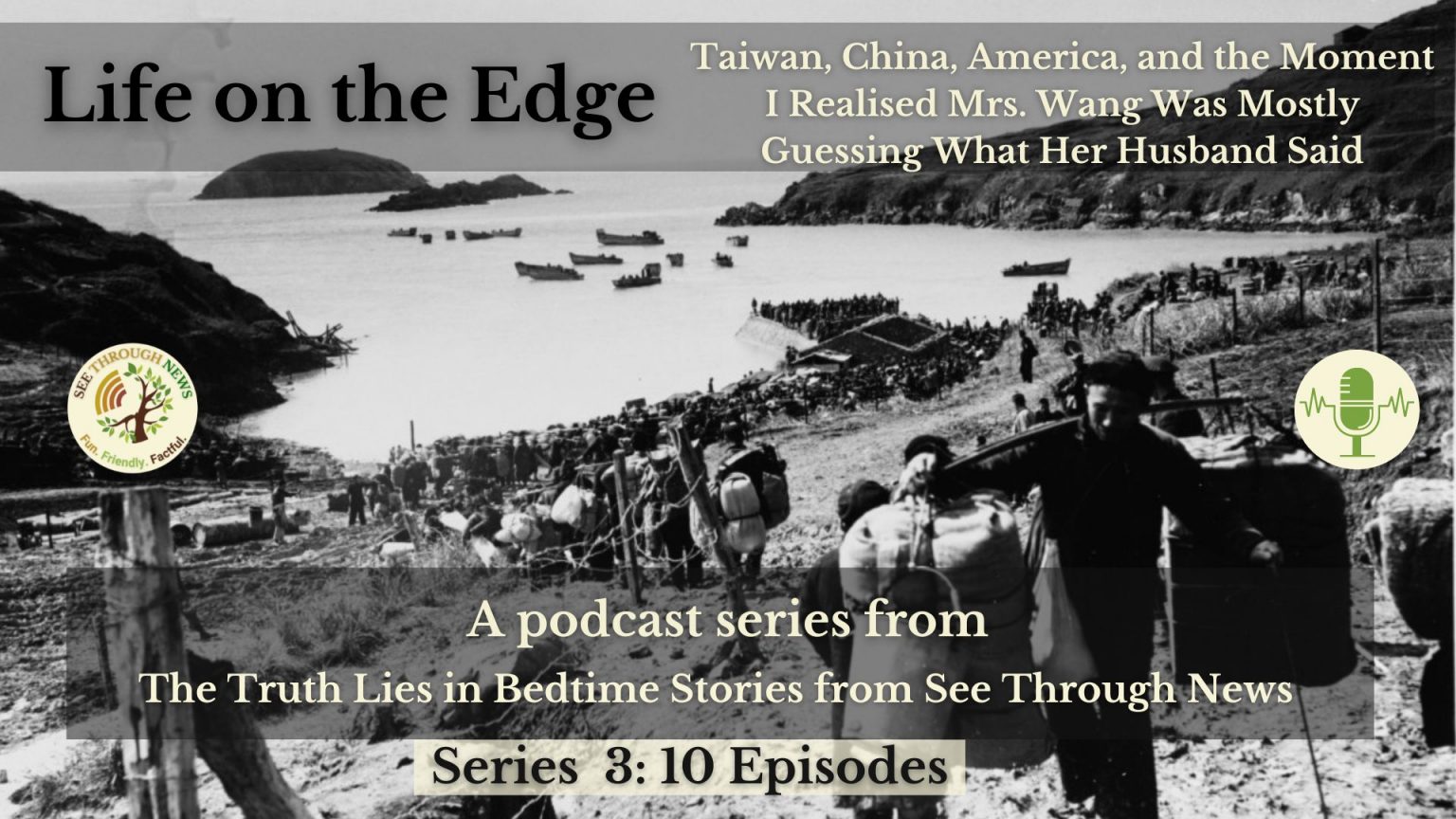

So it was, that as dawn broke on February 10th 1955, the 18 thousand Big Chen Islanders woke to find themselves surrounded by American warships, with smoke from the PRC warships steaming towards them on the western horizon.

And that was why islanders were banging pots and pans to raise the alarm.

That was why an American sailor had just barged into the house of the Brothers Wang, telling them everyone had to leave right now, or become Communist.

That was why Middle Wang left a perfectly good breakfast uneaten.

And that was why, fifty years later, in a sweltering living room in suburban Alabama, I asked Mrs. Wang to ask her husband The Wheelbarrow Question.

How, I asked, amid all the chaos of that morning in 1955, with such steep, narrow, crowded paths leading down from their village, had Mr. Wang managed to get the wheelbarrow containing his paralysed little brother as far as the beach?

In Episode 4, The Wooden Wheelbarrow, with the destinies of the Three Brothers Wang suddenly taking different paths, we’ll hear The Story of Small Wang.