What a Twitter-spat about the dark art of plankton-counting tells us about science communication and effective climate action.

This article is an investigative deep dive into a citizen science project that was first unreported, then misreported, and finally – with this article – fully explained.

Part 1: What’s Wrong With Crying Wolf

The Boy Who Cried Wolf. Chicken Little. The Timid Hare and the Flight of the Beasts.

These kinds of tales are so common across time and culture, folklorists assign them their own category. ‘Aarne–Thompson–Uther Type 20C’ stories are cautionary tales that ‘make light of paranoia and mass hysteria’.

Compared to the stories our ancestors heard, modern squeamishness has made the consequences of such folly less gruesome.

Chicken Little/Chicken Licken/Henny Penny/ Høne Pøne/Kylling Kluk/Loosey Goosey, all used to end up gobbled up by a fox.

In today’s gentler times, she merely has her foolish paranoia pointed out to her. An acorn falling on Henny Penny’s head does not mean the sky is falling. On the sub-continent, the sound of a vilva fruit falling on a palm leaf is no reason for the timid hare to trigger a jungle-wide stampede.

The point remains, though. Put scientifically, over-interpretation of single data-points risks category error.

The Boy Who Cried Wolf/The Child Whiche Kepte the Sheep’/De Mendace Puero once suffered terminal consequences, with both sheep and boy being eaten by the wolf. We now downgrade this to ‘learning a lesson’, but the moral is still clear, and is drawn from what happened when The Boy lied, not when he shouted the truth.

The Trojan priestess Cassandra was among many women punished for rejecting the advances of serial sexual predator, Apollo. Her exquisitely tortuous curse was to know the future but not be believed. Her punishment hinges on the recipients of bad news rather than the messenger, but the deeper ‘lesson learned’ is similar:

It doesn’t pay to be a doomster.

Such folk wisdom lies deep within all humans – it’s probably helped us survive so far. But not all human civilization, history and culture is well adapted to the species-level threat we’ve created for ourselves.

Far from helping us, the tribal divisions, national borders, rival religions, competing governance and political systems which have worked for homo sapiens over millennia are proving to be hindrances to survival.

Having set fire to our house by burning fossil fuel over the past couple of centuries, need to put it out, but many ‘lessons learned’ from folk culture are impeding urgent action.

What follows is a modern day cautionary tale. As we don’t yet know the end of the story, we can all make up our own endings, draw our own morals.

Is our protagonist Chicken Little? The Boy Who Cried Wolf? Cassandra, or…

See what you think – here’s the story of Dr. Dryden & The Missing Plankton.

Part 2: Dr. Dryden Sees a Problem

How To Clean Water

Nearly a lifetime ago, a Scot named Howard Dryden did a PhD in marine biology.

He was interested in recycling 100% of fish farm water. Or, in his original scientese, ‘molecular sieve ion exchange zeolitic sand filtration systems for closed system aquaculture’.

On graduating, Dr. Dryden turned the technology he’d invented for his thesis into a successful business career in waste water management.

Back then, sand was used to filter dirty water. Dryden Aqua, as he called his company, used glass. He crushed bottles, treated the ground glass to make more toxins stick to it, and patented the results as Activated Filter Media. AFM, as he trademarked it, was twice as effective at cleaning water as sand.

Today, more than half the glass bottles in Scotland, and Switzerland, are recycled by Dryden Aqua to make AFM.

For the best part of 40 years, Dr. Dryden has cleaned water around the world. Pharmaceutical manufacturers in China, textile factories in Bangladesh, petrochemical plants in South Korea, and many other companies and government operations have sought his expertise.

Then, the world’s biggest public marine aquaria came calling. This route back to his original passion should have been a pleasure, but the more aquarium contracts he fulfilled, the more concerned Dr. Dryden became.

Cleaning sea water for marine zoos was profitable for Dr. Dryden the businessman, but deeply disturbing for Dr. Dryden the marine biologist.

Marine aquaria needed his services because untreated sea water had become so toxic, it was killing their exhibits.

As he tried to work out why, Dr. Dryden started joining dots to other things he’d learned during his decades treating waste water.

Forever Chemicals & Microplastics

Few of us are familiar yet with the term ‘Chemical Revolution’. To anyone dealing with them, like Dr. Dryden, it’s as important as the Industrial or Digital Revolutions.

From the 1940s, we began manufacturing large amounts of chemicals that don’t occur in nature, and introducing them into the environment.

Like the villagers below the Boy’s flock, Chicken Little’s animal friends, or Cassandra’s fellow-Trojans, we’ve had warnings, but have so far largely ignored them.

DDT was an early klaxon. This synthetic insecticide, invented in 1874, was deployed at scale during WW2, then in massive volume in post-war agriculture.

The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring awoke the public to DDT’s disastrous ecosystem impacts. The US banned its agricultural use in 1972, the rest of the world took until 2004.

But DDT isn’t a typical story. Believing their manufacturers’ assurances that their many benefits had no long-term downsides, we’ve allowed thousands of types of ‘forever chemicals’ to be pumped into our environment, unregulated, in increasing volume, for decades.

America has been out in front in producing these families of synthetic chemicals, suffering the consequences, and regulating their proliferation. To most Brits, ‘PFA’ means the Footballers Association, Down Under, the Police Federation of Australia, but increasingly in the US, PFA means Perfluoroalkoxy alkanes.

After decades of systematic suppression of bad news by the chemical industry, long-running lawsuits are starting to reach massive settlements. If you saw Mark Rufallo in Dark Waters, based on Du Pont’s attempts to hush up the toxic legacy of its Teflon plants, you’ll know Hollywood has started placing ‘forever chemicals’ in our eyelines.

Initially, America’s Environmental Protection Agency bought Big Chemical’s pitch that the planet was plenty big to absorb them, and they could be trusted to self-regulate and practice restraint even if they’d invested huge sums in research and building huge manufacturing plants.

Though still hobbled by massive lobbying, the EPA has started ratcheting up the limits it places on what it sees as the worst offenders. Having once treated these chemicals as harmless, the EPA is now defining their toxicity in terms of a few dozen parts per trillion, and rising. To Big Chem’s consternation, the EPS has even started enforcing some of these new limits.

This is a familiar story. Big Tobacco and Big Oil’s attempts to slow regulation of their products used the same playbook, same PR companies, same law firms, the same lobbying system.

We shouldn’t be shocked or surprised – it’s just how unregulated capitalism works. If products are embedded in our daily lives, someone’s making a heap of money from them. That someone is regarded as negligent in its obligations to its shareholders were it not to resist any efforts to make less money, or not recoup on its R&D and plant investment. They only stop when governments issue, and enforce, regulations.

There are thousands of forever chemicals – a recent Lancet report listed 15,000 of them. They include a group that caused Dr. Dryden particular concern.

Inspect the labels on the bottles under your sink, or the small print on any cosmetics in your bathroom cabinet and see how many include ‘Oxybenzone’, ‘Octinoxate’ and anything ending in ‘-paraben’.

The water treatment industry’s historic mantra has been ‘the solution to pollution is dilution’, in which the world plays a bit-part as an infinitely large trash bin. Eventually, forever chemicals end up in the biggest trash bin of all, the ocean.

80% of waste water enters the sea untreated, and not all the 20% that passes through treatment facilities catches these toxins. Those that do concentrate them into a toxic sludge, which still has to be disposed of somehow, and one way or another often ends up in the sea anyway.

What regulation we have has largely been driven by lawsuits proving danger to humans.

But plankton don’t sue.

Dr. Dryden started to wonder how many ‘drops in the ocean’ it would take before the concentration of these new, persistent chemicals, to which nature has not adapted, started to exceed the negligible, homoeopathic, levels claimed by their manufacturers.

He’d observed, before most of the rest of us, the build-up in marine microplastics, and began to join these dots:

- Many forever chemicals, like the oxybenzone used in sunscreen, are lipophilic (i.e. attracted to fats)

- Plastics are hydrophobic (i.e. resistant to water, which is why they don’t dissolve and disappear)

- In combination, bits of forever chemicals in the ocean will tend to stick to the increasing bits of microplastics in the ocean, concentrating their toxins.

- These toxin-loaded microplastics will enter the marine food chain.

- Micro-plankton – tiny animals and bits of vegetation floating in the water that form the basis of the marine food chain – will ingest these toxin-laden microplastics.

What, wondered Dr. Dryden, are the numbers?

At what point should we start worrying about these converging, apparently unconnected, trends?

Earth’s Alien Environment

One of the more surreal sketches from 1970s British TV comedy involved The Two Ronnies reclining on deckchairs, staring out to sea. After a period of reflection, one says to the other ‘It’s so huge, the sea, isn’t it?’. ‘Yes’, replies the other, ‘and that’s just the top of it’.

Which is to say, we know remarkably little about the oceans.

NASA says we have better maps of Mars’s surface than we do of Earth’s ocean beds and know more about the composition of Saturn than 70% of our planet’s surface and the waters above it.

10% of humans are ‘highly dependent’ on marine ecosystems, billions nourish themselves from the sea, but climate physics mean even landlocked Mongolia herders or Saharan nomads ultimately depend on the seas.

Specifically, we depend on plankton.

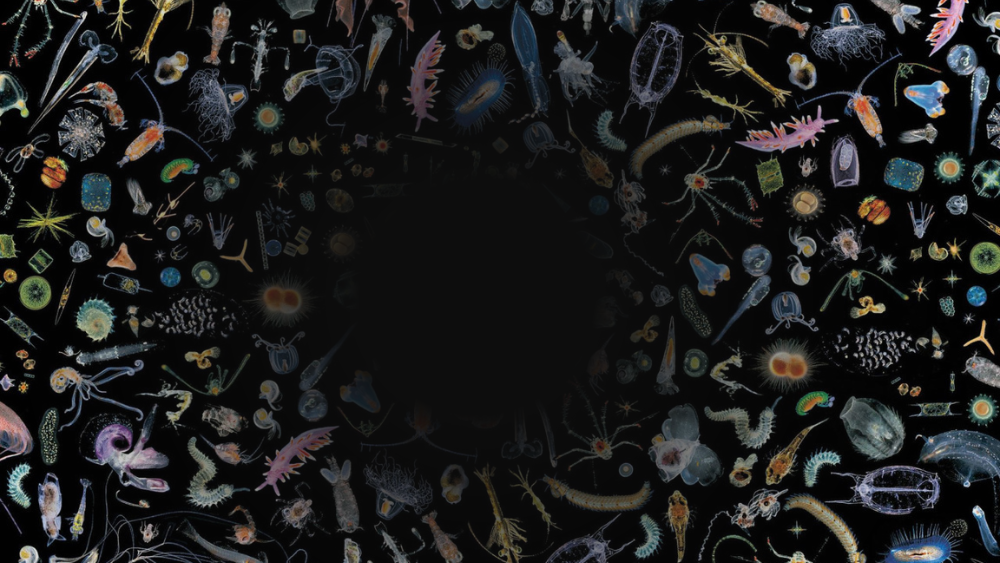

Plankton, from the Greek ‘planktos’, meaning ‘to drift, wander’, are the tiny bits of vegetable and animal life that float in the sea. Apart from sustaining all marine life, plankton provide around half of the oxygen in the atmosphere. Plankton removes CO2 from the atmosphere, when they die, bury carbon at the bottom of the ocean.

If you can spare 15 minutes, make yourself a cup of tea and watch Ocean Drifters, made by Dr. Richard Kirby, the Plankton Pundit of Plymouth.

If you’re not too mesmerised by astonishing plankton images, or bewitched by David Attenborough’s narration, Ocean Drifters explains the key role this microscopic organisms play in planetary life and physical cycles, and human history.

Plankton create clouds, chalk and cement, form the ‘fossils’ in fossil fuels, and provide half the oxygen we breathe.

Ocean Drifters describes how during The Beagle’s voyages in the 1830s, Charles Darwin cobbled together a net made from bunting, trawled it behind the boat, and noted the tiny animals it captured.

In 1931,The Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey was set up to measure oceanic plankton levels, taking hundreds of thousands of samples from waters around the world ever since.

Their plankton data is used by governments around the world as a bellwether for long-term climate-related policy-making.

But counting plankton over long time periods is a really hard problem. Not only are oceans vast, and plankton tiny, but there are many different techniques for sampling and counting them.

The CPRS’s great merit is that it has used the same methodology since 1958. On the plus side, it’s measuring like with like. On the minus, we’ve developed many other ways of catching and sampling plankton, and of looking back in time via clues and proxies. Plankton respond to many complex and ill-understood physical and biological factors, are not evenly distributed in the ocean. Try counting them in different places at different times and you’ll come up with very different numbers.

In 2010, a Nature paper estimating that marine life was declining by 1% a year made the leap from academia to newspaper front pages.

It’s an instructive prequel to Dr. Dryden & The Missing Plankton. This paper, though peer-reviewed before appearing in the most prestigious academic journal imaginable, still spawned a feeding frenzy of controversy amongst oceanographers, the mainstream media, and social media

Scientific criticism focused on how, in order to compile a database covering a 100-year period, the survey stitched together data using two different counting methods. Some found the paper’s justification convincing, others thought this discrepancy could account for the falling plankton numbers.

First mediated by mainstream media, then amplified by social media, the public debate split along established tribal affiliations. Team ‘I Knew It!’ welcomed the report as vindication of their fears. Team ‘Can’t Be True’ rejected it as evidence of boffin bias. Few minds were changed.

Most of us quickly moved on, distracted by our latest global recession. Oceans may have absorbed 93% of the heat from burning fossil fuels we’ve burnt since 1971 (the atmospheric calamity being the result of the other 7%), but few of us have a clue what 240 zettajoules means. Besides, trees are more photogenic and familiar than plankton.

This highlights a problem for all forms of science communication, particularly climate science.

Scientists are often the worst people to cry wolf. Their training deters them from bold statements or colourful language. They think data speaks for itself. They’re wary of overstating their case, straying too far from the dry, bleached-out language of academia, of jumping the gun.

Of shouting wolf. Of warning the sky is about to fall on our heads.

Take Project Drawdown, where world experts in a huge range of fields calculate and rank the cost and efficacy of various carbon-reduction activities. It’s critical work on which all governments and individuals should base every decision, but their website requires several clicks to access the most important league table in human history.

Scientists can make it hard for the average person to understand the importance of their work, but Dr. Dryden knew how to read a technical paper.

After trawling through all the academic literature, his questions were:

- How much plankton is there?

- Are we measuring the right things in the right way to know the answer?

He decided to find out for himself.

Part 3: Dr. Dryden’s Solution

An Unusual Caribbean Retirement

A couple of years ago, Dr. Dryden sold most of his shares in his company, and his partner Diane Duncan retired from public health administration. They bought an ocean-going yacht, named it the Copepod, and sailed the Atlantic.

Unlike most retired couples yachting in the Caribbean, they sought out local fishermen and quizzed them on their catches. They tested water samples. They saw the sudden increase in the volume of sargassum seaweed washing up on Caribbean islands. They researched why it contained such high concentrations of arsenic.

They set up a citizen science project, called it the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey (GOES), and established a land base for coordination and data analysis at Edinburgh University’s Roslin Innovation Centre.

GOES focused on what they referred to as the lesser-reported, but no less devastating,‘Evil Twin’ of the Greenhouse Effect – ocean acidification.

Dr. Dryden was particularly shaken by the papers published by Bioacid, the ocean acidification research programme based in Kiel, Germany that’s authored a series of increasingly disturbing reports in top academic journals.

Scientists compiling the IPCC reports having been ringing alarm bells about Bioacid’s reports, and similar ones from other ocean acidification programmes, for years, but you wouldn’t know it from mainstream media headlines. Maybe they should re-name themselves, The Crying Wolf Mission, or Project Cassandra.

Here’s what they’ve found. As we emit more CO2, the ocean absorbs more of it, and turns a tiny bit more acidic. Some numbers:

- Pre-Industrial Revolution, the sea’s pH value was around 8.2.

- Today it’s 8.04 and falling.

- ‘Business as usual’ means it will be 7.95 by around 2045.

At pH 7.95, sea water dissolves the carboniferous shells that keep most plankton alive, form the coral reefs that protect half a billion humans ashore. At 7.95 the basis for our entire marine ecosystem could be made homeless, and die.

Dr. Dryden’s trans-Atlantic voyages on the Copepod gave him the idea of using fellow-sailors as volunteer citizen scientists to collect water samples.

He read up on current methodologies for data collection, analysed the basis for current estimates of plankton numbers, consulted marine researchers on their predictions for plankton numbers in the mid-Atlantic, where the Copepod has sailed

Our oceans may be poorly understood, but scientists and institutions are constantly researching them and publishing data. Many are well-funded, and have been around for decades. Ambitious, then, to think a few volunteer sailors could contribute anything useful.

On the other hand, few working in academia possess Dr. Dryden’s particular experience and expertise, acquired from decades in commerce.

Using his engineering, chemical and filtration experience, and his and Diane’s savings, Dr. Dryden tinkered with and troubleshooted an idea he’d come up with after reading the academic literature.

A new way of counting plankton.

Dr. Dryden’s Odd Bird-Feeder

Dr. Dryden set himself the task of designing a foolproof system that could be used by ordinary sailors.

The result, a 500ml capacity plastic tube, with dark green fittings at the end, which looks a bit like a bird feeder.

GOES recruited and trained ocean-going yachters in their use. The basic procedure:

- Insert high-grade filter paper into the collection tube.

- Trail the collection tube behind their boats to capture sea water.

- Remove the filter paper, capture an image using a USB microscope GOES provides.

- Email the pictures to Edinburgh for analysis.

- Repeat.

A dozen boats took on the challenge in the Atlantic. Including yachts in the Pacific and elsewhere, more than 30 citizen scientists around the world are now following Dr. Dryden’s procedure as they sail the seas.

When the GOES Foundation started analysing the results back in Edinburgh, they didn’t know whether to be puzzled, or panicked.

Part 4: Troubling Results

A Plankton Out of Water

As someone who turned his PhD into a business, Dr. Dryden knows the difference between the worlds of academia and commerce.

Universities require you to establish general truths with a view to expanding human knowledge for its own sake, while publishing your discoveries as widely as possible.

Business requires you address specific challenges case-by-case with a view to exchanging goods & services for money, while keeping your secrets secret.

Increased university reliance on private-sector funding has blurred some lines, but the cultural abyss remains as deep as the Marianas Trench.

Most scholars and businesspeople still suspect each other’s motivation. Unsurprisingly, each considers their own world superior.

Typically, academics regard doing anything for profit as intrinsically compromising, suspecting business folk take short cuts or massage data to suit their bottom line.

Typically, business folk see themselves as practical and effective, and academics as detached, self-indulgent, and chasing funding fashions.

Dr. Dryden’s decades at the coal face started in the ivory tower, but that was a lifetime ago.

Now he was doing self-funded citizen science for public good, he needed new contacts, different kinds of colleagues, relationships based on mutual trust and shared interests, not commercial advantage and signed contracts.

The wet bit was fine. Ocean sailors tend to be a tight, mutually supportive bunch, so finding fellow-yachters to volunteer as citizen scientists was relatively straightforward.

The dry land stuff was more challenging.

Alongside the waste water industry trade journals, Dr. Dryden had kept abreast of academic research, but hadn’t published anything academic himself since his PhD.

He and Diane started reaching out to leading plankton researchers to answer his two questions – how much plankton would experts expect to find, and is the current method of counting them the most accurate?

The benefits of the Continuous Plankton Research Survey are many and obvious: a huge mass of data, taken over decades, using a consistent methodology. It’s what scientists dream of, and rarely find.

Like others before him, Dr. Dryden wondered if modern technology and understanding couldn’t improve on the 1958 gold standard employed by the CPRS. Would looking in the same parts of the ocean with different technology get the same results?

This, essentially, is what the GOES Foundation citizen science project sought to do.

A decade after the controversial 2010 Nature report, counting tiny plankton in vast seas was no less challenging.

Even experts could get things wrong. One big-budget project, using remote-controlled, unmanned, sonar-enabled, AI-controlled mini-submarines to count krill, couldn’t understand why they weren’t finding a single one, until someone fooling about with the controls accidentally pointed it upwards. Only then did they realise the support ship above had a powerful light beam shining down. Krill flee direct light.

Such blunders apart, plankton-counting isn’t like quantum physics, where the act of observation can affect the outcome. The oceans may be huge, but there’s an objectively truthful number of plankton floating in it. Any credible methodology, executed with consistency, accuracy and diligence, should produce roughly similar results.

Dr. Dryden’s experience of keeping exhibits alive in aquaria gave him a hunch things might be worse than we realised. Most research projects and businesses start from hunches, but all require numbers if you want anyone to take you seriously.

The Importance of Numbers

Dr. Dryden described GOES equipment and methodology to their new academic contacts, and asked them:

Based on current understanding of plankton numbers, how many would you expect our method to catch?

The consensus was somewhere in the range of 1-5, with a likely average towards the lower end of that range. That is to say, given the particular part of the mid-Atlantic being sampled, the half-litre capacity of the collection tube, the spec of the filter paper, the time of day being sampled etc. etc., and so long as no one screwed up or sabotaged the process at sea or in the Edinburgh office, the consensus of expert marine biologists, up to speed with the latest data, was that the GOES project would find between 1 and 5 bits of sea life on every disc of filter paper.

‘1-5’ is a big spread, but this reflects the difficulties of counting plankton. Oceanographers like to say ‘the physics drives the biology’, by which they mean big effects like ocean currents and temperatures creating downswells and upswells, are what distribute the nutrients sought by plankton at different depths and locations. To know where to look, you need to take all these complex interactions into account, and even then the target areas are much too big to be measured.

The sampling methodology adds yet another level of complex variables to the physics and the biology: what with, how often, how much, what speed, what depth, what transects, what grid pattern.

As the results started to come in from the yachts sailing from Europe to the Caribbean, however, it was clear something, or someone, was very wrong.

Back in the Edinburgh land base, the GOES team inspected the images pinging into their inbox.

They were far from blank. The magnified specks and dots on the filter papers showed lots of bits of carbon residue from the bunker fuel used by ships (‘bunker’ means any fuel used on a ship, but it tends to come from the lower, dirtier fractions of petroleum distillation). They also revealed plenty of bits of microplastics. No surprises there.

The surprise was no plankton. Zero. Zip. Zilch.

Image after image, dozens and then hundreds of them, showed no organic life at all. Well, occasionally they’d find the odd plankton, but functionally, statistically, there appeared to be barely 10% of the bottom end of the range predicted by the academic experts.

Their bird-feeder method was clearly catching inorganic bits and pieces of microscopic size, but why not living things?

Dr. Dryden cross-checked, using a net-trawl method similar to the one used by the CPRS, in the same waters, at the same time of day. The net trapped a higher volume of water, so should have ironed out some of the data noise resulting from relatively low sample numbers.

Same result. Lots of pollution from shipping fuel and microplastics, barely any plankton.

What’s An Academic Paper?

Dr. Dryden started the laborious and time-consuming task of assembling his research to meet the standards of an academic paper.

He asked around for advice on current practice, and heard about a new option – the ‘pre-publication’ platform SSRN.

The Social Science Research Network started in 1994 as a disruptive, democratised, dot-com alternative to the fusty, slow world of conventional academic peer-review publishing.

The idea was that, in the increasingly fast-paced internet era, anyone could upload interim results or pre-publication drafts to SSRN’s website, and crowdsourced feedback from online experts would inform and improve any papers then submitted to orthodox, peer-reviewed journals. An Internet-enabled adjunct to conventional science paper publication, designed to make the process more accurate, efficient and fast.

Disruptive dotcoms rarely preserve their founding ideals – Google dropped their ‘Do No Evil’ tagline once they started making money, and ‘spare room share’ Airbnb became something very different one it found its monetising model. Most, of course, never make it past the funding stage.

But SSRN was a hit. By 2016, when SSRN was bought by the Netherlands-based scientific publishing giant Elsevier, it was already the biggest online repository of academic papers, and has kept growing since.

For some, Elsevier’s ownership confers a much-needed academic imprimatur of respectability. For others, it was a down-market commercial move to a quick-and-dirty platform that devalues the rigour required by ‘proper’ peer-reviewed publishing.

You won’t be surprised to learn that people from outside academia tend to favour the former view, established academics the latter.

On balance, Dr. Dryden thought pre-publication of his data via SSRN might help prepare his research for peer-reviewed publication. He also wanted to alert the world to his potentially troubling findings.

So he uploaded an interim draft to SSRN.

What happened next takes us from the realm of science, to the knowledge food chain.

We now enter the separate worlds of how mainstream media reports science, and how the Internet responds to those reports.

It gets ugly, nasty, messy, and complicated, but may well be the most significant part of this cautionary tale.

Part 5: Released Into The Wild

How To Ignite A Media Firestorm

Dr. Dryden uploaded his paper to SSRN June 8 2021, titled:

Climate regulating ocean plants and animals are being destroyed by toxic chemicals and plastics, accelerating our path towards ocean pH 7.95 in 25 years which will devastate humanity.

The language of the paper follows the same tone, neither drily academic, nor breathlessly tabloid, somewhere in between. About right, then, for SSRN.

The result…nothing. Zero. Zip. Zilch.

No helpful experts offered insightful suggestions on how to adapt it for peer-review. No armchair experts noticed. No activists Tweeted.

It was like Dr. Dryden’s experience aboard the Copepod mid-Atlantic: no whales, no sea birds, no fish, only yourself for company.

GOES Atlantic volunteers kept sending their samples in, now joined by another dozen or so in the Pacific. As the data grew, Dr. Dryden updated the SSRN paper, most recently on May 2 2022.

Then someone at The Sunday Post got in touch and arranged an interview.

As Scots, Howard Dryden and Diane Duncan were delighted. The Sunday Post is something of an institution throughout Scotland, Northern Ireland and Northern England.

Started in 1914, still published in Dundee, home of ‘Jam, Jute and Journalism’ by DC Thomson. They’re best known for comics like The Beano and The Dandy, but also publish many respected news titles. The Sunday Post, a weekly tabloid with a lively, engaging voice, blends news, human interest stories, short features and cartoon strips like Oor Willie and The Broons.

Like all newspapers, the Post’s print circulation declined steeply from its historic high of 700,000 at the turn of the millennium, but it’s still popular and, for a tabloid, well-regarded.

On July 17 2022, to Dr. Dryden’s astonishment, the Post not only printed something about his research, but splashed it all over its front page. The headline was a characteristic mix of Scottish parochialism and global doomsterism:

Our empty oceans: Scots team’s research reveals loss of plankton in equatorial Atlantic provoking fears of potentially catastrophic loss of life

Over 1,800 words – a very long piece for the Post – the article quoted Dr. Dryden and his research at length. There were also quotes from Greenpeace Scotland, the Marine Conservation Society Scotland, and the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency, but their generic nature suggested they were not familiar with the specifics of the GOES research.

The article has an unusual amount of scientific detail, but what unleashed a media storm was its 4th sentence:

Previously, it was thought the amount of plankton had halved since the 1940s, but the evidence gathered by the Scots suggest 90% has now vanished.

This is not what Dr. Dryden had suggested – his research data was only from the equatorial Atlantic. and he’d not extrapolated this to all the world’s oceans.

But ‘suggest’ is a very handy word for popular science reporting. ‘Suggest’ is a journalist’s version of oxybenzone, the forever chemical found in sunscreen that’s so toxic to plankton, providing a degree of protection invisible to all but lawyers.

Think of all the tabloid headlines about boffins ‘discovering’ cancer is causedby/prevented by wine/chocolate/meat/jogging. There’s usually a ‘suggest’ in there somewhere, placating pedants who let facts get in the way of a good story.

On July 23rd, a week after publication, The Post corrected its article online to clarify this point. It even noted this correction in italics at the end of the article:

This story was edited on 23 July 2022 to make clear the samples studied by the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey Foundation were taken from the equatorial Atlantic and have not yet been confirmed by other scientists or research teams.

Over-egging has long been the tabloids stock-in-trade. Since the Internet ate their lunch, newspapers have joined the clickbait game. Upgrading 90% of the mid-Atlantic to 90% of the world’s oceans is anti-science and dodgy journalism, but it’s undeniably good for business.

To be fair to the Post, its correction is the kind of ethical and responsible journalism not often associated with tabloids.

But it was too late.

The ‘90%’ had been released into the wild. On The Internet, there’s no putting genies back into bottles.

Internet Discord

After months of being ignored, the Sunday Post front page sent Dr. Dryden’s Plankton Bombshell ballistic.

The ‘90%’ was Internet box office, red meat for both sides of the climate ‘debate’.

To the Activists, it was more of The Science to back their increasingly desperate calls for action.

To The Sceptics, an open goal to undermine, snipe at, and mock the credibility of The Science.

Some examples from Team Activist:

- Please read this, then start ASAP to do what you think you can do, including circulate this. I have personally spoken with Dr Howard Dryden the founder of GOES and his associate in South America: they aren’t joking or exaggerating: we ARE in a bad way

- Plankton in the Atlantic Ocean is 90% gone. @goes_foundation warn that an environmental catastrophe is unfolding. Here at Seaspiracy, we can only attempt to express the urgency and deep sadness for this shocking news.

- You are so right Howard but mass populations are indoctrinated by Media and and Governments

- Wake Up End Time News: !!ATLANTIC PLANKTON ALL BUT WIPED OUT IN CATASTROPHIC LOSS OF LIFE!! Revelation 8:9 a third of the living creatures in the sea died, and a third of the ships destroyed. #WAKEUP #BIBLEPROPHECY #MASSANIMALDIEOFF #FORESHADOW

Some examples from Team Sceptic:

- It’s literally impossible that he’s right here. Absolutely impossible.

- there is sufficient evidence of a dire global environmental catastrophe without making shit up.

- If I don’t listen to Howard Dryden’s pseudoscientific bullshit, THAT would be dangerous apparently.

- There is zero reason to talk to Water filter sales man, & yachting enthusiast, Dr Howard Dryden to clarify what he thinks. His ‘reports’ (i.e. non peer reviewed opinion pieces), websites & comments online speak for themselves in garbled tones, & they show him up to be a crank.

- “The plankton are dead!” Doomer reddit keeps dredging up only the most credible research to boost to the top page. -the article has less text than some postal stamps -no link to report -research team’s site really raises eyebrows Just proof of an alarmist headline’s sheer power.

We applied the See Through News triage system for social media shitstorms:

- Discard any criticism that’s solely ad hominem, ‘to the person’, i.e. attacking the messenger rather than the message. This usually reduces the total by around 90%, which says a lot about most online ‘debate’.

- Sift through the remaining arguments that are ad rem, ‘to the thing’ – ad hominems’s lesser-known Good Twin.

- Isolate specific, verifiable points, and find experts to fact-check them.

Here’s one response that made the cut, from online news website Ars Technica. The bold highlights are our additions, signifying the bits we marked to verify or challenge. It’s quite long because we’ve left the ad hominem bits in too:

For the past few days, it has been hard to look at social media without coming across a scary-looking report from the Scottish newspaper The Sunday Post. “Scots team’s research finds Atlantic plankton all but wiped out in catastrophic loss of life,” reads the breathless headline. The article claims that a survey of plankton in the ocean found that “evidence… suggest[s] 90% has now vanished.” The article then goes on to predict the imminent collapse of our biosphere.

There’s just one problem: The article is utter rubbish.

The Sunday Post uses as its source a preprint manuscript—meaning it hasn’t been peer-reviewed yet—from lead author Howard Dryden at the Global Oceanic Environmental Survey.

There’s no denying that our oceans are in trouble—the study notes in its introduction that they have lost 50 percent of all marine life over the past 70 years, and that number is rising at around 1 percent per year. But the Post’s article goes further than the preprint, citing plankton counts collected by 13 ships with 500 data points.

Specifically, the article claims that the survey “expected to find up to five visible pieces of plankton in every 10 liters of water—but found an average of less than one. The discovery suggests that plankton faces complete wipe-out sooner than was expected.”

Five hundred data points collected from 13 vessels sounds impressive, but David Johns, head of the Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey, describes it as “a literal drop in the ocean.” Johns would know—the Continuous Plankton Recorder Survey has been running since 1958 and has accumulated more than 265,000 samples.

The Continuous Plankton Survey has indeed cataloged a loss of plankton over the years—but nothing close to the 90 percent loss claimed by Dryden. “We have noticed long-term changes—northerly movements of plankton species as surface water warms, changes in seasonality in some taxa, invasives, etc.,” Johns told Ars by email. “And we work with a wide group of scientists and governmental bodies, providing evidence for marine policy. As a group, we had an email discussion, and no one agreed with this report—and no one had heard of the guy (other than one person, and she was not complimentary at all).”

In addition to the small sample size, the preprint makes no mention of how or when the plankton samples were collected. “If those samples were taken during the day, in surface waters, there is likely lower numbers of zooplankton,” Johns explained. “Also, [there is] no mention of what magnification [the researchers] were using. If you were using a low-power microscope, you would struggle to see the small stuff—in warm open ocean Atlantic waters, much of the zooplankton is pretty small, and they might have trouble picking them out.“

As noted above, the paper that the Post based its article on has not been peer-reviewed, an apparent theme for Dryden. “It seems he doesn’t really have a scientific profile—none of his work seems to be peer reviewed, which is obviously important when you are making any bold claims,” Johns told Ars.

And Dryden is making bold claims. Although he raises the very real problem of ocean acidification, he has appeared to blame the problem on microplastics and not climate change caused by a massive increase of atmospheric CO2 levels. However, in this preprint, Dryden and his co-authors do identify atmospheric CO2 as the driver of ocean acidification, which they warn will result in the loss of 80–90 percent of all marine life by 2045.

This takedown’s withering tone might lead you to imagine the author, a certain Jonathan Gitlin, has a long experience and deep expertise in marine biology. He’s a pharmacist.

(This is an example of an ad hominem attack. If we told you the author of the article you’re reading has a degree in Classical Chinese Poetry, would that make any difference to you? Bias is easy to spot in others, but not everyone is always conscious of their own.)

The Ars Technica article quotes a critical CPRS interviewee who makes specific reference to Dr. Dryden’s research. The last paragraph sets up a straw man, only to knock it down, but overall, how did this critique strike you? A decent bit of journalism?

The glaring omission is Dr. Dryden himself. We suppose they didn’t ask, as when See Through News contacted Dr. Dryden, he couldn’t have been more amenable. We arranged an interview within 24 hours, despite being on opposite sides of the Atlantic, several time zones apart.

We used the time to contact some online critics, and expert oceanographers, to refine the Plankton Counting Question List to put to Dr. Dryden.

Our Zoom call ended up lasting a couple of hours.

It answered certain questions, but begged many others.

Part 6: Zoom Call with the Copepod

View from the Copepod

Diane Duncan, Dr. Dryden’s life and GOES partner, joined us from Edinburgh, where she was checking in at the land base. After wry observations about the weather in Colombia, Edinburgh and Wiltshire, and setting our Zoom call to record, we got down to business.

Pen poised above our Plankton Counting Question List, See Through News prepared to grill Dr. Dryden on his research.

But Dr. Dryden was off. He embarked on a detailed description of the underlying science, chemistry, and before we could intervene, its technology and methodology.

Monopolising interview time is often a sign of rampant ego, defensive filibustering or intellectual arrogance, but as Dr Dryden continued his monologue, occasionally supplemented by Diane in Edinburgh, we found our Questions being ticked off, one by one, with all the scientific context we could have asked for.

By the time Dr. Dryden had completed his introduction, around 90 minutes had elapsed, but he’d addressed all the points raised by the Ars Technica article, plus many others, and in some style. It felt like attending a very fascinating lecture, rather than being a passenger on an ego trip.

The Ars Technica journalist and CPRS source were quite right to query the specifics of the GOES collection methodology – the time of day, magnification, and size of target plankton.

Here’s a summary of Dr. Dryden’s description of the methodology being used by GOES v. the CPRS ‘gold-standard’. See what you think:.

- The CPRS uses 270 micron filters. GOES uses 20 micron spec filter paper. i.e. the GOES filters should catch things more than 10x smaller than the CPRS.

- The CPRS filters capture sea water from approx. 10m below the ocean surface. GOES samples come from top 1m, i.e. where you’d expect more marine life to be, night or day.

- CPRS vessels sail at 20-25 knots. GOES yachts at 10-15 knots, i.e. samples are less likely to be washed away due to the speed the filter travels through the water.

- CPRS data is collected at many different times of day. GOES volunteers take their samples in two windows, noon-2pm, and midnight-2am, confirmed by geodata, because at the ocean surface, as in rainforests, very different animals and plants appear daytime v. nighttime.

Fact Checking Matters

Dr. Dryden would make a good teacher – his explanations are authoritative, clear and methodical. But of course we can’t take everything he says as Gospel, and Wikipedia isn’t always detailed enough.

See Through News fact-checked Dr. Dryden’s methodology with experts from the plankton-counting Establishment. Hearing experts uncover new levels of nuance and complexity in unfamiliar subjects is one of the perks of investigative journalism. It’s like climbing hills, with each new false peak revealing how much further you still have to go. Or unlocking new levels of a video game. We imagine.

In one such time-zone-busting fact-check, we spoke to Jim Massa, an Alaskan-based oceanographer who used to work on the Arctic Survey and now has a YouTube channel called ‘Science Talk’ explaining climate-change related scientific papers for non-specialists.

Massa spent years getting brine in his beard, conducting large-scale, publicly-funded plankton surveys. He had an additional tranche of questions about Dr. Dryden’s methodology, not currently answered by the GOES website or SSRN paper:

- Sampling: ‘Are transects being done – both meridionally and zonally at regularly spaced intervals? This is a problem even with doing transects at regular spacing between stations. You simply miss the critters. So, I see this as a problem’.

- Boat speed: ‘Dragging a sampling device behind a vessel is not optimal based on my experience. Usually, what is done is we go to a station, stop the vessel and do vertical plankton tow. The plankton nets are lowered to whatever depth and pulled to the surface’.

- Nets: ‘Usually, we are dealing with nets 1 meter in diameter and are sent down as attached pairs. (We call them bongo nets)’.

- Location: ‘Low plankton abundance in equatorial waters is not a surprise. Equatorial waters have always been low in productivity due to a nearly permanent thermocline that prevents vertical mixing of nutrients into the photic zone. Toss in the findings that many planktonic species are moving to higher latitudes because the ocean is too warm gives the impression that plankton numbers have dropped a lot when it comes down, to not sampling in the correct area because they moved. This is where doing meridional transects is important’.

We’re calling time on the forensic, back and forth, because this is a journalistic article, not a science paper, and don’t want to lose anyone who may find they’re plumbed the depths of their fascination with plankton-enumeration.

We were struck by something else Jim Massa said.

But, you try to explain this to the general public who only want sound bite headlines and well, you get the brouhaha we got. And this is another problem – short attention spans.

The science is a big enough problem, but the answer isn’t always more science. We’ve known about the theory of global heating since for 150 years, and its reality since the 1970s. We’ve always possessed the technology to mitigate it, but have chosen not to, due to that elusive chap, Political Will.

Massa mentioned the oceanographer’s mantra of ‘The Physics drives the Biology’, but the See Through News mantras, based on our decades-long longitudinal study of Tricephalous Bestiology, is ‘The Politics Drives the Physics’, ‘The Media Drives the Politics’, ‘Business Drives the Media’ and ‘The Money Drives The Lot of ‘Em’.

For climate scientists, deciding to go public is a tough decision. Some experts we contacted for this article didn’t respond, others were very helpful but wouldn’t go on the record. They’d seen the toxic social media fallout from the Post’s article on Dr. Dryden’s research, and didn’t want to risk contamination.

Massa’s point about short attention spans can afflict scientists who brave the social media scrum. The CPRS spokesman quoted in the Ars Technical article either knew all about Dr. Dryden’s methodology and neglected to mention it, or hadn’t gone to the trouble of finding out before publicly issuing ad hominem-heavy criticism. He probably didn’t have time to go into much detail, but there’s the dilemma right there.

Maverick cranks and obsessive nutters, spouting distracting, ignorant or irrelevant pseudoscience, are the bane of scientists’ lives. But scientists representing large institutions like CPRS should also be aware of a long history of academics and institutions being proved wrong by independent researchers, who benefit from different experiences and perspectives.

One of the greatest such mavericks has just died, on his 103rd birthday. In the 1960s James Lovelock, a medically-trained doctor, posited the Gaia hypothesis, suggesting the Earth functions as a self-regulating system. Many great scientists ignored, derided or dismissed ‘Gaia theory’ – some still do – but new research has been supporting Lovelock’s vision ever since. Gaia Theory, and Lovelock himself, entered the scientific mainstream. Among his many other achievements, in 1986 Lovelock was elected President of the UK’s Marine Biological Association.

Here’s the perspective of another of Dr. Dryden’s more credible online sceptics, and prominent Twitter presence on climate issues, Dr. Eliot Jacobson.

Jacobson’s CV is impressive, indeed rather Lovelockian. His picaresque personal history includes being poacher and gamekeeper in the gambling industry. He made considerable sums beating the odds at casinos and teaching others his tricks, before consulting for the casinos to spot punters using the very card-counting and advantage-play techniques he’d developed and passed on. He then became a professor in Computer Science and Mathematics.

In retirement, Jacobson bills himself in his Twitter profile as a ‘Know-it-all doomer’. Most of his thousands of Tweets apply his powers of statistical and mathematical analysis to issues of climate science. Most point out we’re far more ‘doomed’ than we understand.

Here’s the Tweet that attracted our attention:

Dr. Howard Dryden fooled me once with an article about ocean acidification, now I am hyper-aware that his claims have not been peer reviewed. A good lesson I didn’t have to learn a second time. I’m not saying he’s wrong ~ it’s just not good science.

Prof. Jacobson proved to be as amenable to rational analysis as you’d hope a retired professor of mathematics would be. He happily engaged in an email back-and-forth ahead of our interview with Dr. Dryden.

Jacobson has personal experience of non-peer-reviewed platforms. Having published more than 300 articles in the same manner himself, he declares himself to be ‘a big fan of the freedom that not being peer reviewed provides’.

When pressed, via email, to be specific about his objection to Dr. Dryden’s work, Jacobson gave a more nuanced version of his Tweet.

You could characterize my principal objection as being that his conclusions are pre-mature and require further research to corroborate his results. I am certain he would agree that a second study coming to the same conclusions, one that is published in a peer review journal, would be a paradigm-changing event for the future of climate science and the planet.

Jacobson also referenced something to which See Through News, like any responsible news outlet, always pays close attention – the Money, of which more later.

When there is money on the line, that’s when peer review gets going. So we’ll see what comes of Dryden’s work. If it impacts a company’s bottom line in any way, there will surely be profit-driving peer review. If not, it will survive until some academic with nothing better to do decides to have a go at checking the results with his own peer reviewed study.

We Get A Word In

Back aboard the Copepod, Dr. Dryden finally finished his background lecture. Now was our chance to ask the remaining unticked questions on our list.

First was the much-discussed matter of the lack of peer review. This was swiftly dealt with.

Dr. Dryden said he’s talking to an academic institution right now about collaboration on a paper to submit to a peer-reviewed journal. He should be able to confirm within a few days, and reckons a paper should be ready for peer review submission within weeks.

This timeline may carry the whiff of someone more accustomed to the pace of commerce than academia, but still… all that fuss, all that casual, contemptuous, corrosive online dismissal from all those armchair arbiters, all over a few weeks.

Dr. Dryden gave every impression of someone who’d relish spending the rest of the day answering questions about filter paper specs, oceanic PH measurement methodologies, and unregulated forever chemicals, but he had another Zoom interview lined up.

So we moved on to something See Through News seemed to find far more interesting and important than Dr. Dryden or Diane Duncan did – the Sunday Post article and subsequent online reaction to his SSRN report.

We were speaking a few days after the Post front page splash, with the ‘90%’-induced Twitterstorm in full swing.

It was hard to tell whether Dr. Dryden was blissfully unaware, willfully ignorant, naively optimistic, or stocally indifferent when it comes to the online carnage being wreaked in the name of his research.

He and Diane seemed more amazed at the fact the Post had plastered them all over their front page. They’d only expected a few lines buried on an inside page.

Dr. Dryden alerted The Post to its misattribution of the ‘90%’, clarifying his fleet of 13 volunteer vessels were only taking samples from the mid-Atlantic, not the entire ocean. This was the detail that had triggered so much online Sturm und Drang. Dr. Dryden appeared to take this with equanimity, treating it as more of a minor squall than a major storm.

He even blamed himself, rather than clickbait-hungry tabloid copy editors, for the misunderstanding. He thought he should have explained his methodology more thoroughly. Maybe that was why he’d just invested 90 minutes in ensuring See Through News was fully briefed.

All in all, Dr. Dryden didn’t come across as media-savvy, or even media-obsessed. He seemed happiest when talking science, engineering and procedure, content to let his work speak for itself. Challenged with some of the more ad rem criticisms, he was unperturbed.

Talking to Dr. Dryden, below deck on the Copepod, moored off Colombia, you don’t get the impression he’s a raving egomaniac, or a publicity-seeking huckster. Diane neither, at the GOES Edinburgh HQ, eager to name the scientists they’d consulted when doing their research, typing links and references into the chat box as she or Dr. Dryden cited them.

See for yourself. Dr. Dryden on Zoom comes across very much like Dr. Dryden in the YouTube video of his COP 26 talk he returned to Glasgow to deliver in November 2021. His claim that this was COP’s first-ever talk on the subject of oceans is astonishing, but verifiable.

Dr. Dryden is not a natural public speaker, nor is he comfortable in the limelight. He comes across as sincere and passionate – definitely a scientist, more comfortable with numbers and data than eye-catching graphics or ear-catching turns of phrase.

Here’s one last Tweet before drawing any conclusions in the final part of Dr. Dryden & The Missing Plankton.

It’s from Steven B Adler, CEO of the Ocean Data Alliance. After Dr. Dryden’ explained on Twitter that the ‘90%’ was the Post’s misreporting, and not his claim, Adler sent this terse scold in response:

It is your job to check stories before they are printed.

This is literally untrue – checking stories is definitively the job of the reporter/editor, not the subject of the story.

It’s also unfair – however meticulous you may be about being on/off the record, at some point, journalists and their interviewees have to develop some degree of trust.

Hollywood celebrities and pop stars have editorial approval written into pre-interview contracts – do we really want, or expect, the same thing for Dr. Dryden?

Above all, this comment seems to get to the heart of this tale.

Much as Dr. Dryden would like this to be a story about the science, focused on the micron-spec of the filters, and the minutiae of comparative plankton-sampling methodologies, and much as he may be right to think so, it clearly ain’t.

Dr. Dryden & The Missing Plankton has turned out to be more of a morality play, a pre-cautionary tale of the dysfunctional relationship between objective science, mainstream media, and social media, and the way nuance, truth and facts get lost in the gaps that separate them.

There’s a reason why spin doctors, press agents and PR consultants always go on about ‘controlling the narrative.

It’s all about the storytelling.

Part 7: The Moral of Dr. Dryden’s Story

Well, Is Dr. Dryden Right or Wrong?

If you feel this story has become a bit directionless, like a plankton, or a becalmed yacht trapped in sargassum, hang in there. We’re setting course for some Conclusions.

If you’re impatient to hear our judgement on whether Dr. Dryden is Right or Wrong, a Good Man or a Bad Man, you’ll have to wait a bit longer.

If we’re to learn anything from the story of Dr. Dryden and The Missing Plankton, it’s to be wary of having an opinion for the sake of it.

We reckon Dr. Dryden will get his research into a shape that a respectable journal will be prepared to publish, either because of, despite, or irrespective of the Twitterstorm unleashed by the Post article.

It will be peer-reviewed, experts will have their say. We await their conclusions with interest, and a sense of urgency.

This is surely the way we should treat science, so resist the Twitter-temptation to opine, to trash Dr. Dryden’s ideas and evidence simply on the basis of where it’s published, or a tabloid headline, without any attempt to fact-check Let’s avoid the irony of accusing Dr. Dryden for jumping the gun, while lacking the patience to wait a few weeks for the peer-reviewed version. Whenever it comes, the trigger-happy trolls will doubtless find reasons why they were right all along, if they’ve not already moved onto fresh clickbait meat.

It’s understandable why ad hominem Twitter-bickering is more popular than rational, fact-based ad rem debate. No need to confront inconvenient truths, or deal with complex, inter-related consequences. Personal beef, online ding-dongs distract us from urgent action or hard decisions.

Let’s return to that repository of human wisdom, folklore, that started this journey.

The example of Chicken Little suggests we shouldn’t make major economic and societal shifts based on a few hundred water samples taken by volunteer yachters. Dr. Dryden could be crying wolf not out of mischief, but good intentions.

But what if he’s a Cassadra, cursed to know the future and be ignored?

To dip into the amphibian category of folk tales, are we frogs in boiling water, or at the bottom of wells?

Forget folklore – there’s always a counter-example, and none of it is verifiable. Let’s try logic instead, or plain common sense.

Time, and peer-review, will tell if Dr. Dryden’s citizen science project is a canary in the coalmine that escaped the experts until now, or the misguided fumblings of a oceanographic amateur, out of his depth.

But why not take action even if he turns out to be wrong?

Isn’t what we already know already shocking enough? No one credible seems to dispute that human activity has already lost us half our marine biomass. That’s with 7.8 billion of us already, projected to grow to 11.2 billion by 2100, and all the locked-in consequences of all the fossilised plankton we’ve already burnt.

We’ve heard the social media-amplified objections to Dr. Dryden’s attempts to count the Missing Plankton before, directed at the other Evil Twin, atmospheric CO2.

Crazy cranks. Doomsters. Unproven. Experts disagree. We need more evidence. This or that detail invalidates the whole thing, etc. etc. All reasonable-sounding excuses for inaction.

Incredibly, we still hear such objections, even as Prof. Jacobson, James Lovelock, are among many so-called ‘doomsters’ who believe we’re already too late to arrest runaway feedback loops, with devastating consequences for human civilisation.

Bill McGuire, emeritus professor of geophysical and climate hazard of University College London, has just published Hothouse Earth. His unflinching verdict? All those reassuring voices telling us ‘there’s still time’ are whispering infantilising ‘climate appeasement’. It’s time to face up to the tipping points we’ve already triggered. Not to give up, because catastrophe isn’t binary – we can still avoid making things even worse, but are unlikely to take any action while we’re still in denial about what we’ve already done. ‘Save The Planet’ protests by children who’ll have to live through the worst of it, if they’re lucky, still go unheeded.

It’s human civilization we need to save, incidentally, not the planet. Planet Earth is 4.5 Bn years old, 99.98% rock, and has already hosted mass extinction events,5-7 of them, depending on how you count them. ‘The Planet’ will keep on spinning for billions more years just fine without us.

Homo sapiens, on the other hand, has only been around 200,000 years or so. Conflating the fate of our species with that of the planet betrays the very arrogance that created this mess in the first place.

Call it the Holocene or the Anthropocene, but the mass extinction event now underway is the first caused by a species, rather than meteorite strikes or other physical events. It’s by far the most rapid.

Selfishness, impatience and striving for dominion have got humans where we are. Unsurprisingly, they’re hard habits to break.

But we also have other, better traits on which to draw in our hour of peril.

We started this story looking at folklore, and how embedded folk wisdom is in our way of thinking, whether we realise it or not. All cultures have some version of ‘a stitch in time saves nine’, or ‘don’t spoil the ship for a pennyworth of tar’.

These are vernacular versions of the Precautionary Principle.

Scientists, philosophers, engineers and lawyers invoke the Precautionary Principle to justify taking small actions now as insurance against unproven, but potentially huge, future disaster.

Politicians rarely invoke The Precautionary Principle. Magic Bullets, future technology, dei ex machina are much more effective, as they mean we don’t have to change anything.

We let our leaders promise us we don’t have to change anything, because most of us fear change.

But not if we know the consequences of not doing so are worse.

Covid has provided a perfect example. Our leaders told us that we couldn’t possibly accept lockdown or compulsory mask-wearing. Then we saw the images of overwhelmed hospitals in China and Italy, and decided we would.

It’s all about how we frame the choices, which stories we’re told.

Picture A shows the Lake District as it is. Picture B shows it covered in wind turbines. Which you prefer?

What if we tear up Picture A, and show you Picture C, the Lake District on fire, or Picture D, underwater, or Picture E, with half a billion climate refugees. Magically, the one with the wind turbines becomes the obvious choice.

This is why storytelling is so important, and why the lessons to draw from Dr. Dryden and the Missing Plankton are less about The Science, and more about the Chinese whispers by which it’s communicated.

All of us, voters, politicians, businessmen, bankers, shareholders, could benefit from a bit more personal and species-wide humility when it comes to the profundity of our ignorance.

This is not another snipe at Pharmacists or Mathematicians pontificating on matters of marine biology – that would be ad hominem, and we’re doing our best to keep things ad rem.

It’s about our propensity for clever dickery, smart alecry, knee-jerk trashing of notions we find uncomfortable, unwelcome or inconvenient. Social media didn’t create this human trait, but turbo-charges its insidious impact.

The nature of Dr. Dryden’s online abuse is revealing. We’re most likely to accuse others of sins of which we ourselves are guilty. A fraudster thinks a lot about fraud. Hypocrites are particularly sensitive to hypocrisy. Egotists are quick to identify others as being in it for themselves.

Follow-The-Moneyists will note many of Dr. Dryden’s loudest supporters and critics have something to gain financially from getting out in front first, and bellowing their verdicts in the most extreme manner through their virtual bullhorns.

Those Twitter followers and YouTube subscribers can, and are, being monetised. To be cautious is to veer off-brand. To say nothing is to miss a business opportunity.

This article has so far used reported speech, rather than direct quotes, to tell Dr. Dryden’s story.

It’s a kind of stylistic writing trick, to make the story more allegorical and less personality-driven, but here are Dr. Dryden’s own words, aboard the Copepod off Cartagena, Colombia, explaining why he and Diane Duncan are spending their retirement, and their savings, counting plankton:

If you’re aware of what we’re aware of and do nothing about it, then that’s almost a criminal offence. Ethically, we couldn’t continue in our day jobs. So I sold off most of my shares in Dryden Aqua, bought a blue-water sailing vessel, and said OK, if that information isn’t really out there in the detail that we require, let’s go and get it.

The Media Food Chain

When See Through News first saw this story, it looked like a straight-up reporting job. Sift through the heaps of unshucked oysters the Internet is bickering over, and uncover the pearls of verifiable fact.

But it’s turned into something else, a story about how science is transmitted, and what happens as it passes along the food chain.

Forever chemicals and microplastics provide a useful metaphor here.

Dr. Dryden is driven by his mission, but he’s a mild-mannered individual with a scientist’s precision and caution, flagging when knowledge crosses into speculation, very specific about details. A dilute solution of an active ingredient.

As Dr. Dryden’s research passes up the media food chain, it’s broken down, attracting more toxins which become more concentrated each time they’re ingested.

As it passes through a Sunday tabloid splashing it on its front page, nuance and detail are excreted.

Each time Dr. Dryden’s research is paraphrased, re-interpreted and chopped into shorter and shorter bites, for shorter and shorter attention spans, the stripped-down, bite-sized micro-remains become more toxic.

By the time they reach the apex predator, Twitter’s 280-character binary echo-chamber, the original idea is almost meaningless, a convenient carrier for whichever beast happens to have chosen this social media nutrient to feast on.

To adopt another Dr. Dryden simile, the Sunday Post acted like an Activated Filter Medium for his research, attracting all its toxic elements and concentrating them into toxic sludge.

Activists and Sceptics act like hydrophobic microplastics. They’re attracted to ‘90%’ headlines as irresistibly as lipophilic chemicals are to microplastics, with similarly toxic results for our online ecosystem.

Some denizens of the climate niche of this ecosystem find this sludge repellant – unfortunately the very ones from whom we could most benefit, like the experts who helped See Through News with this article, but demurred from going on the record.

Even the most anodyne quote, brings the risk of contamination if connected to Dr. Dryden’s research. This is understandable, but unfortunate. It doesn’t bode well for finding the best peer reviewers.

Pop-Quiz Epic Fail

Pop Quiz Q1: What’s the most numerous plant on the planet?

A1: Procholorococcus. If you’ve not heard of it, and are wondering what it looks like, don’t beat yourself up. You’d need a microscope, it’s among the smallest things in the sea. It’s a marine cyanobacteria. It was only discovered in 1986. Oh yes, and it produces 20% of our planet’s oxygen. And captures 20% of its carbon. And microplastics are toxic for it.

Pop Quiz Q2: What’s the most numerous animal on the planet?

A2: Copepod, after which Dr. Dryden named his boat. Not a household name outside the Dryden household, and copepods don’t appear in many children’s storybooks. Yet twice a day, when these microscopic organisms migrate up and down 200m to feed at the surface, they displace more water than the moon does. Copepod crap contains 30 times more carbon than we burn in fossil fuels.

A common online criticism of Dr. Dryden features a kind of competitive Doomsterism, implying you have to pick your favourite Evil Twin, atmospheric CO2 or ocean acidification.

Why put these two catastrophes in competition? It’s as if we can only accommodate one existential threat at a time. Don’t bother performing the Heimlich Manoeuvre on someone choking to death, because they’re not taking their heart medication so will die of a coronary anyway. Surely we should be concerned about, and act on, both lethal threats.

Actually, this analogy fails. Unlike choking and heart disease, greenhouse gases and ocean acidification share a root cause – burning too much fossil fuel too quickly for Gaia to adapt.

There’s little point in dodging one bullet, only to let another hit you between the eyes.

The science of ocean acidification is just as incontrovertible, its causes just as clear, its trend just as precipitous, and its consequences just as terrifying, as the more familiar threat of greenhouse gases.

So why, to the frustration of Dr. Dryden and other marine biologists, does it get so little attention?

Let’s return to NASA’s observation about our relative ignorance about what goes on in our oceans. We can see the moon, even Mars, but not the 70% of our own planet’s surface that’s submerged.

Like grandparents, tap water or air travel, we take things that have always been around for granted. We only notice their fragility when they go wrong, or miss them when they’re gone.

Here’s a story that just appeared in the papers. Stripped down, it becomes a three-sentence mini-parable.

- Metals like copper, nickel and cobalt, key materials for ‘green’ technologies, are in high demand.

- The sea-bed of a patch of the mid-Pacific called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone appears to be rich in these ores.

- An exploratory dive to the bottom of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone just revealed the existence of dozens of undiscovered marine species.

We’re not offering any ‘moral’ to this story, only these observations:

- Real world decisions are complex, have unintended consequences, and demand detail and nuance.

- Understanding the extent of our ignorance, and the nature of the trade-offs required is probably more important than any single, simplistic ‘moral’.

- Complexity is not an excuse for inaction.

If you’re now reaching for the bottle, pills or firearm, hang in there a moment longer..

Any discussion of our apocalyptic self-harm should end on

a) a note of hope

b) specific calls to action.

Fortunately, this story has a ringing chord of the former, and three crackers of the latter.

Part 8 Lessons – The Moral of Dr. Dryden’s Story

The Hope Bit

Oceans, unlike forests, act fast.

The marine ecosystem has way more bouncebackability than its land-based equivalent. However rapid the demise of plankton, whatever the actual number between the 50% reduction we’re sure of and the 90% Dr. Dryden fears by 2045, we can be almost 100% confident that if we stop causing the problem, the oceans can recover as quickly as they’ve declined.

Once species are extinct, much of this hope disappears, but for the moment, there are still enough of the right species around to form a starter culture for marine life regeneration.

How’s this for a fanfare of optimism:

- On land, biomass takes around 60 years to double in volume.

- At sea, it takes around 3 days.

If you’re immediately thinking ‘blue whales can’t grow that quick’, that’s a great example of how poor our understanding of marine life is.

60% of marine life is less than 1mm long. This leaves a lot of room for growth. That 3-day doubling probably has something to do with the geometry of surface area – small things can grow much quicker than big things.

Scale matters, and with ecosystems, small tends to be critical. Resentful microbiologists, mycologists and entomologists, always struggling for funding, call the flagship species that appear on posters and logos ‘charismatic macrofauna’.

The pandas, tigers and elephants get all the headlines, and most of our money, but they can only survive if the food chain below them is intact.

Let’s replace our ‘Save The Whale’ badges with ‘Save The Krill’ ones.

Let’s rebrand procholorococcus.

Let’s make posters of copepods.

Let’s celebrate phytoplankton’s photosynthesis as much as that of our terrestrial plants.

There’s still, just, time to stop polluting our waters.

Dr. Dryden’s calls to action are very specific:

- Stop using unnecessary toxic chemicals and plastics

- If we must use them, capture them before they reach the ocean

- Make ships spend a bit more to use cleaner fuel

All very do-able, especially once you understand the alternatives, Pictures C, D, E etc..

Other options include:

- Wait for the boffins to come up with a magic bullet

- Give up

- Insist we ‘wait for more evidence’

All translations of ‘doing nothing’.

‘Waiting for more evidence’ sounds reassuringly responsible and scientific. It absolves us of the need for us to do anything, to change any behaviour, create new regulations or enforce existing ones.

Meanwhile, every CO2 molecule released into the atmosphere is indifferent to who released it, or where, or why. It doesn’t favour any particular species, nation state, race, or political ideology. It just sits in our atmosphere, reflecting energy back on us.

Microplastics, forever chemicals and specks of bunker fuel dirt are just as indifferent. They just act out the laws of physics and chemistry, and the biological impacts follow whatever we choose to do.

So there’s the hope bit. It’s pretty clear, really.

We just have to wake up and take action now.

***

See Through News is a not-for-profit social media network with the Goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping Inactive Become Active. It was founded by Robert Stern (AKA SternWriter) in 2021, receives no funding, and is run by volunteers who share an urgent need to do something by doing something different.

@seethroughnews on your favoured social media platform

To help, email: volunteer@seethroughnews.org

To sign up to our weekly newsletter (direct to your inbox, no ads, no data bought or sold), click here.