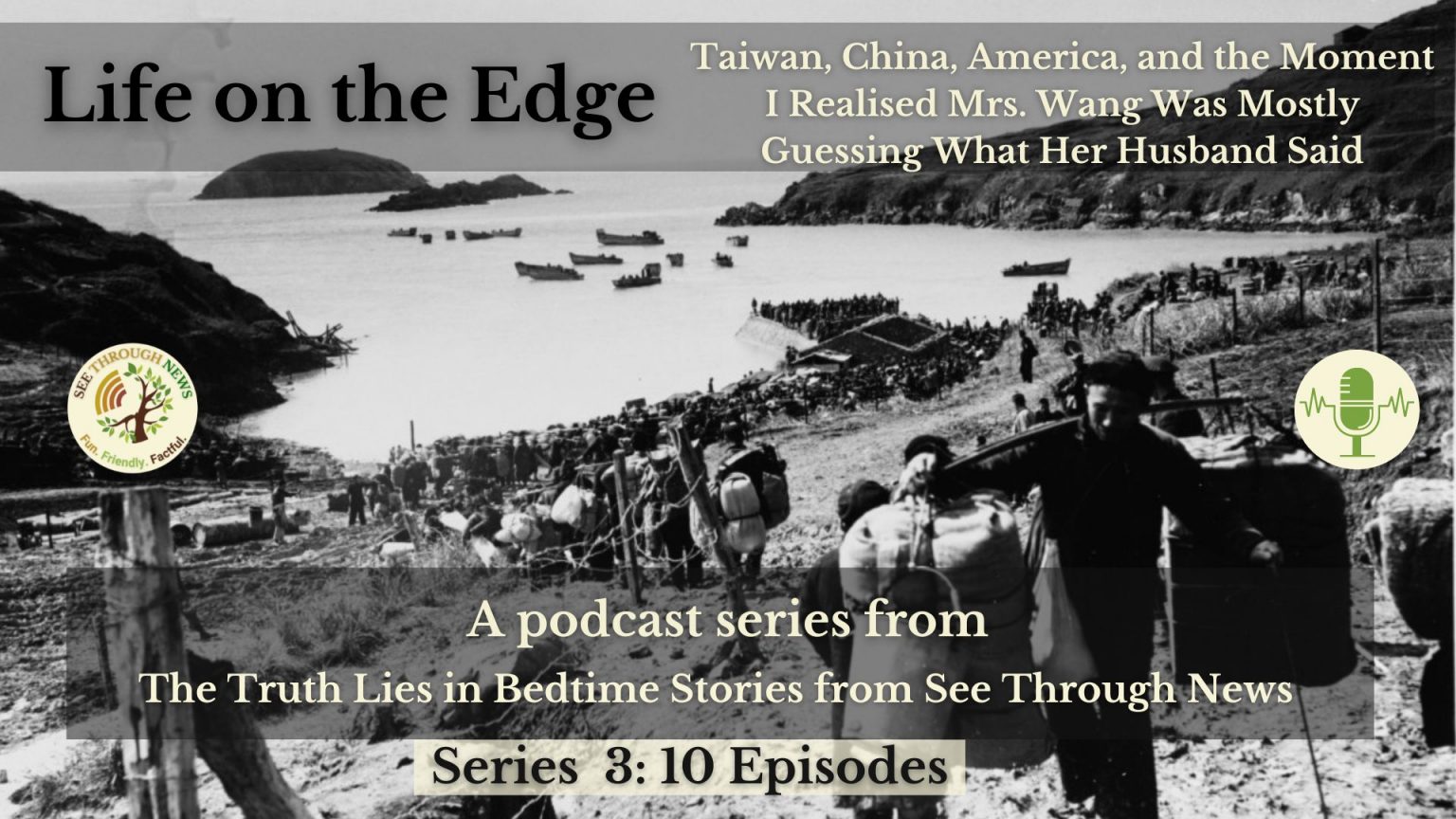

Episode 5 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News‘ podcast

In Episode 5, we learn what happened to Big Wang when he tried to sell his dried squid.

For best results, start this story at the beginning…

Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 6 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Next, Episode 6: The Boy In The Wheelbarrow

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

If you enjoyed this series, why not try these ones…

- Series 1: The Story of Ganbaatar – the only qualified deep-sea navigator in Mongolia

- Series 2: Betrayed – A Tale of Christmas Spiritual Pollution

- Series 3: Life on the Edge – Taiwan, China, America and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said

- Series 4: The Quiet Revolutionary – the heroic role played in a plot to assassinate the King by someone you’ve all heard of

- Series 5: A Classical Chinese Dirty Joke, Told Thrice

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

**

Transcript

Episode 5: Wrong Time, Wrong Place

For an eldest brother, Big Wang hasn’t featured much in this story so far.

Last time we heard, he was popping over to the mainland in his little cargo boat, laden with dried squid, hoping to earn some cash shuttling goods between the ports that lay over the horizon from his island home.

It was his first big solo trip, but everyone, including Big Wang himself, was confident he’d be fine.

So, in December 1954, Big Wang returned the waves of his younger brothers on the pier, before steering into the waves of the East China Sea.

They slapped against the wooden hull of Big Wang’s little boat, the little harbour on Big Chen Island soon disappeared behind his wake.

Big Wang had made the trip dozens of times before with his father and uncles, so he knew the routine.

The crossing was uneventful. Big Wang tied up at the same dock at the usual fishing town, and went ashore to find the familiar traders who’d bid so enthusiastically for Big Chen Island dried squid last trip.

The dock was deserted, which was a first. The market too was deserted, which was downright weird. The wooden huts that served as the wholesalers’ offices were shuttered. When Big Wang shouted a greeting, echoes were his only reply.

Puzzled, Big Wang walked through the market square to the warehouses beyond.

There he found a small group of serious-looking people, standing over a table. They wore dusty blue and green uniforms with red stars on their caps. They were examining sheets of paper covered with numbers, writing and red wax seals.

Had Big Wang been able to read, he would have noticed the freshly-painted signs on the warehouse doors no longer bore the names of the merchants.

Had Big Wang thought to make discreet enquiries, he could have learned the new characters proclaimed them to have been commandeered by the local collective to store their produce.

Had Big Wang known the uniformed officials were debating how to implement the latest personnel demands from Beijing, he would have turned on his heel, walked directly back to the dock and sailed straight home to his brothers on Big Chen Island.

Instead, Big Wang greeted the stony-faced group with a cheery wave, and asked if they’d like to buy some dried squid.

What Big Wang didn’t realise was that the China he’d landed at this time, was a very different China from the one he’d experienced on his previous trips to the mainland.

Or rather the changes that had been spreading over the rest of China, had finally percolated to his backyard.

It was now five years since Liberation. The chaos of war was now quelled. Refugees were back home, China’s borders were secure – almost.

Chairman Mao was directing mopping-up operations that within two months would leave Small Wang as Big Chen Island’s only inhabitant. But the new regime had much grander ambitions.

China was starting to implement Communism.

The New China was already two years into the Chinese Communist Party’s first Five Year Plan. It was finally filtering down to the remoter fringes of the People’s Republic.

The changes were radical, but after what they were now calling a ‘Century of Humiliation’, they were, broadly speaking, welcomed.

Generations of Chinese had lived through Opium Wars, colonial humiliation, the fall of the last Qing Emperor, the failed Republic, warlordism, even more brutal colonial occupation, a world war, and yet more, even more devastating civil war. By now, they were more than willing to try something new.

For Big Wang, approaching the group of uniformed officials was his introduction to Communism, and it changed his life forever.

For a start, he was told his dried squid was to be immediately commandeered in the service of the people, and his boat.

After glancing at each other, the serious-looking officials asked Big Wang for his name.

They wrote it down on a piece of paper. They told Big Wang to press his thumb into a little dish of sticky red wax, and mark his thumbprint beside his name.

He was now, they told him, formally registered as a member of the local collective.

They had another piece of paper already prepared – the one they’d been discussing before his arrival.

Name. Wax. Thumbprint.

With that, their little administrative problem, the tricky quota Beijing had just sent them, was solved.

The Red Army, so badly depleted following the Korean War, needed new recruits. Beijing had commanded them to supply a volunteer from their collective, and Big Wang had just been volunteered.

Thus did Big Wang, who’d only popped over to the mainland to sell some dried squid, spend his next four decades as a soldier in the People’s Liberation Army.

He never set foot in a boat, but appropriately for a Big Chen Islander, Big Wang was always on the periphery, always at the margins, as China’s communist experiment progressed.

Big Wang was at boot camp in Chongqing when news of the liberation of Big Chen Island was announced through the parade ground loudspeakers.

He tried to find out details, but this was 1955 and he was 17 hundred kilometres from home.

Over the years, he heard rumours Chairman Mao had transplanted a nearby mainland village to repopulate his island home. Every man, woman and child, every buffalo, pig and chicken.

But by this time Big Wang was patrolling border fences on the Burmese border.

In 1959, he was sent to quell Tibetans who didn’t want to be Liberated.

In the early 60s, he patrolled the Yalu River, wielding huge binoculars to spot North Koreans swimming south across the border, looking for a less brutal place to live.

From 1966-1976, Big Wang saw out the Cultural Revolution defending China’s remotest western borders with Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Kazhakstan and Afghanistan.

In 1979 he was deployed back down south, and lost an eye during the Sino- Vietnamese war.

In the 80s, as India and Pakistan started getting fussy about their borders, one-eyed Big Wang found himself back in the mountains.

By the time Big Wang had heard about the suppression of anti-revolutionary students in Tiananmen Square in 1989, it was all over and the crackdown was in full swing.

In 1995, at the age of 60, after 40 years serving in the People’s Liberation Army, Big Wang was allowed to retire.

He received his demobilisation papers, and a small pension, in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia.

With nowhere else to go, he thought he might as well go home.

In Episode 6: we discover what happened to Small Wang, in his wheelbarrow on the beach.