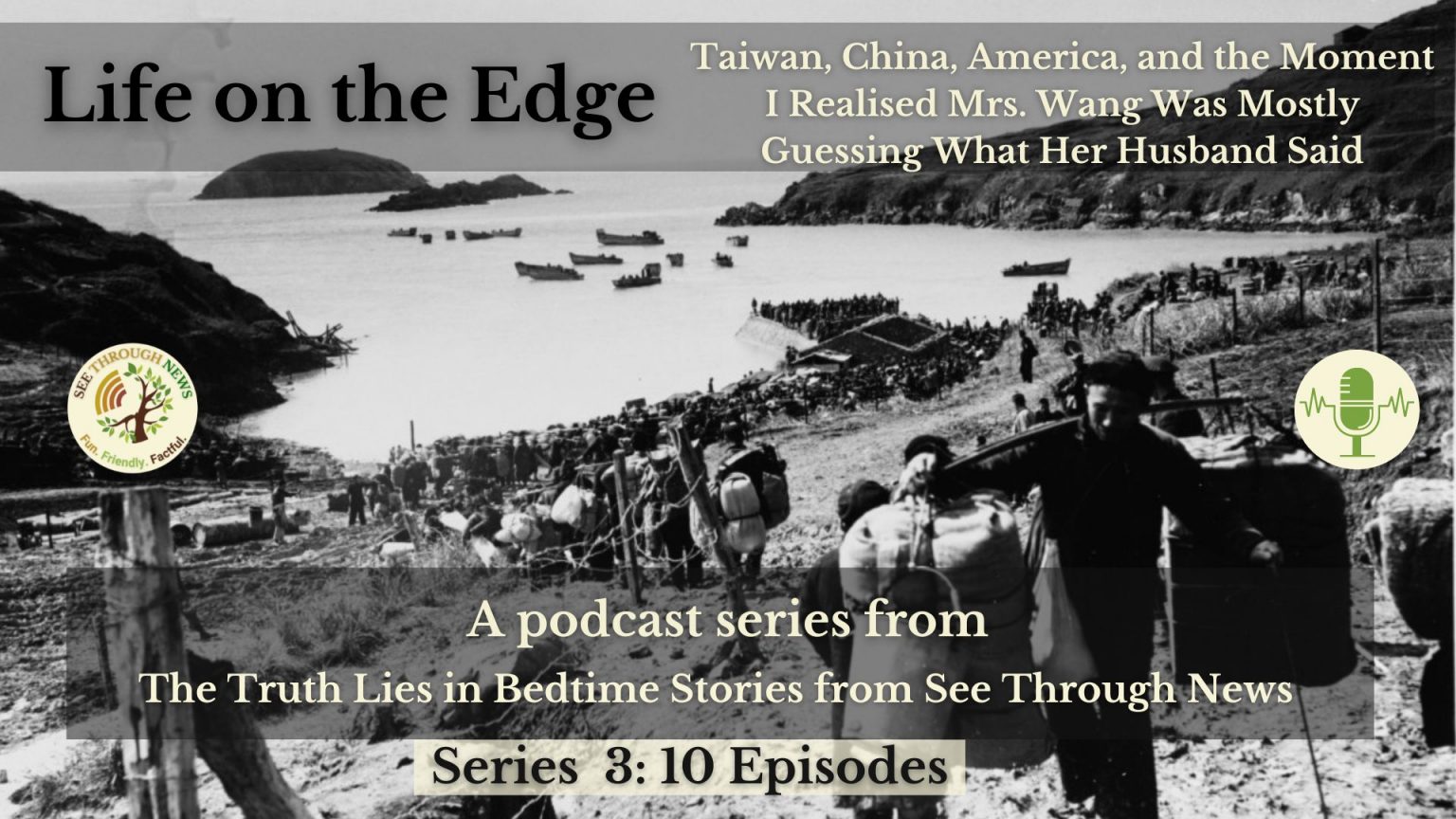

Episode 8 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News‘ podcast

In Episode 8, we learn what happened to Small Wang, abandoned on the beach in his wooden wheelbarrow.

For best results, start at the beginning:

Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 9 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition

Next, Episode 9: Return to Big Chen Island 1

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript

Episode 8: The Man In the Wheelchair

You’re up to speed with Big Wang, heading home after 40 years on China’s borders, after being press-ganged into joining the People’s Liberation Army at the age of twenty.

You’re also up to date with Middle Wang, his thirty years in ships galleys and twenty in Alabama’s kitchens, following his traumatic departure from Big Chen Island at the age of 18.

But before we find out if they ever met again, what of Small Wang, who we last heard of Feb 10th 1955, addressing the first Communist to set foot on Big Chen Island, at the age of 16?

You may remember, the People’s Liberation Army officer had just asked him if he was the only person left on the island, and he’d replied, from his wooden wheelbarrow on the beach, in fluent Mandarin.

You may also remember, that as that officer stepped off his landing craft, Small Wang had no idea if he would be shot, garlanded or ignored.

Well, you’ll be relieved to hear he wasn’t shot.

You may not be surprised to hear he wasn’t garlanded.

But I hope you’ll be pleased to hear, he wasn’t ignored.

Small Wang was, however, at first treated with great suspicion.

The communist soldiers inspected his wheelbarrow carefully for booby-traps and explosives – such things were conceivable to Korean War veterans.

They kept Small Wang under armed guard until they’d finished a thorough sweep of the island.

As it made its way around Big Chen Island’s every nook and cranny, The People’s Liberation Army liberated peckish hens, hungry pigs, cows with full udders, but no other humans.

The liberators found perfectly good breakfasts, smouldering fires in stoves. They even found valuable trophies, tools and trinkets left behind, at least anything that couldn’t be fitted into a pocket.

Aware of Big Chen Island’s reputation as a haven for smugglers and pirates, the Liberators looked for signs of recently-disturbed earth near any dwellings, or recently-removed floorboards or panels inside them.

Maybe it had been too well concealed, but there was no hastily-hidden treasure to be found.

All this came as a total surprise.

The troops and sailors had been told they’d be liberating 18 thousand oppressed fishermen and peasants from tyranny. The younger recruits had expected this to mean arriving at beaches filled with cheering locals. More experienced veterans thought they might encounter some guerrilla resistance.

But none of the liberating army soldiers and navy sailors imagined they’d be greeted by a 16-year-old paraplegic in a wheelbarrow – and no-one else.

They had of course seen the furious activity of the US Navy fleet in their binoculars, but not close enough to see its purpose.

They’d planned for some kind of naval phoney war with the US Navy. Chinese military strategists, familiar with American doctrine from the Korean War, had warned them to prepare for some kind of show of defiance by the Nationalists and their American capitalist running dogs.

That’s why the liberating fleet had steamed so slowly, sending up only slender tendrils of smoke from their funnels as they approached the Big Chen Island archipelago.

Chairman Mao, after all, had specified only a date for Big Chen Island’s Liberation, not a time.

They were in no hurry. Their task was to liberate, not engage in unnecessary direct military conflict with the world’s biggest nuclear superpower.

The army and navy officers, peering through their binoculars, had interpreted all those American boats and planes and helicopters as bit players in some kind of Cold War Theatre, a final act of defiance.

Given the inevitability of their victory, the Communists were more than happy to bide their time. They set their engines to Dead Slow to watch the show, ready to crank them up to Full Steam Ahead the moment it was over.

Had the US naval commander of Operation Pullback known this, he may not have issued his order for immediate retreat.

Had he not issued this order, that last US sailor pushing off the last US landing craft may not have been quite so panicked.

Had he not been quite so panicked, he might have been able to help Middle Wang lift Small Wang safely aboard.

But he didn’t, he was, and we’ll never know.

This is what happens in conflict, even when the war is Cold.

Imperfect information. Seat-of-the-pants decisions. Bluff and counter-bluff. The fates of individuals and entire nations rest on thousands of domino-effect split-second judgements.

Soldiers are told to expect the unexpected, but once they landed on Big Chen Island, what these soldiers discovered was not a scenario for which they’d strategised.

Great mounds of provisions, intended to impress and win the hearts and minds of the grateful proletariat, had been rapidly deployed. Having found the island heartless and mindless, these now lay along the sand, a row of beached whales.

The sapper units, which had sprinted off to sweep the island, ambled back, reporting not a single booby-trap, bunker or bolthole.

The liberating soldiers, braced for action when they jumped onto the beach, now lounged on the beach, as the morning sun warmed the island.

Some, responding to the increasingly insistent calls of the livestock, were feeding the chickens and pigs, even milking the cows.

At this point the intelligence officers interrogated Small Wang to account for this, the only scenario they hadn’t prepared for.

At first, their tone was aggressive and suspicious.

Small Wang simply described what he’d seen, accurately and frankly. He’d seen a lot, his descriptions were very accurate, so before long his questioners conceded his frankness too.

Interrogation gave way to conversation, and soon to admiration of this 16-year-old paralysed kid in the wheelbarrow, who spoke such clear Mandarin.

They asked Small Wang about hiding places of smuggled goods and pirate booty, but with the same candour and sincerity, he replied he knew nothing about that kind of thing.

**

A few days later, nearly 2 thousand kilometres to the north, in the heart of the capital Beijing, in the main bedroom at Zhongnanhai, the former Forbidden City home of the Emperor, piles of books of classical Chinese literature and history were temporarily removed from the enormous bed, where the Chairman now spent most of his time.

A map of the East China coastline was spread out on the wrinkled bedsheets, a briefing delivered. Officials waited for the Chairman’s decision.

Chairman Mao nodded solemnly, rolled over to the map and prodded a pudgy index finger at a particular village, before dismissing the officials and calling for a massage.

Spectacular consequences of casual finger-pointing are among the perks of dictatorship.

A few weeks later, the entire population of the mainland village on which his pudgy finger had landed, and all their worldly goods, were transplanted to Big Chen Island.

Big Chen Island’s new residents soon found themselves relying on its only remaining resident, as they made their lives in their new home.

From his wooden wheelbarrow, soon upgraded to a proper wheelchair, The Oracle of Big Chen Island would tell them:

Which crops would thrive, and where to plant them.

Where the weather came from, and what to look out for.

Where the squid mate, where the sharks lurk, where the crabs hide.

One by one, the new Islanders would call by to consult Big Chen Island’s mobile library. One by one, Small Wang would lend out the thousands of precious nuggets of local knowhow he’d secreted and organised in his remarkable brain.

Carers were assigned to look after this precious resource round the clock. The Oracle of Big Chen Island was given the choice of wherever he wanted to live on the island.

Small Wang chose the simple cottage where he and his brothers had grown up, and instructed his carers to keep it exactly as he remembered it.

The only addition was his wooden wheelbarrow, now standing at the end of the garden by the path leading down to the beach.

He instructed his carers on how to plant it with nine-story-pagoda basil, Big Wang’s favourite herb, the one Middle Wang had been chopping that morning of Feb 10th 1955 when their kitchen door burst open, the American sailor started shouting, and the brothers’ paths parted.

As years passed, the new islanders settled into their new home. They needed to consult the Big Chen Island encyclopaedia in Small Wang’s head less frequently, but they’d still stop by to seek his advice on personal matters, or opinions on events.

Some of them, after a shifty glance to make sure no one else could hear, would ask him if he knew where the treasure was buried.

Small Wang always gave the same answer he’d given to his interrogators when they’d asked him, sounding just as candid and sincere.

So, for a paraplegic who’d feared his first encounter with Communists might leave him with a bullet in his amazing brain, this was about as good a life as he could have dreamed of.

Small Wang’s disability meant he was never going to be at the centre of things. He’d always occupy the fringes of society, but at that precarious moment on the beach at the age of 16, he could hardly have expected his life would have turned out like this.

His lungs, however, never strong, were not getting any stronger. As the 1950s ended, then the 60s, the 70’s, and the 80s, Small Wang’s lungs became weaker and weaker, his world smaller and smaller.

He’d ask his carers to park his wheelchair at the end of the garden path, by the wheelbarrow, now bursting with a fine crop of nine-story-pagoda basil.

He’d sit there for hours, as if waiting for someone to come.

Not just someone, of course, but two people in particular.

In Episode 9, Return to Big Chen Island 1, we find out if Small Wang ever did see either of those two particular people before he died.