Episode 7 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News‘ podcast

In Episode 7, we learn what happened to Middle Wang after he left his little brother on the beach.

For best results, start at the beginning:

Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 8 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Next, Episode 8: The Man In The Wheelchair

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript

Episode 7: The Circumnavigating Cook

For days after he abandoned Small Wang in his wooden wheelbarrow on the beach, Middle Wang spoke to no one.

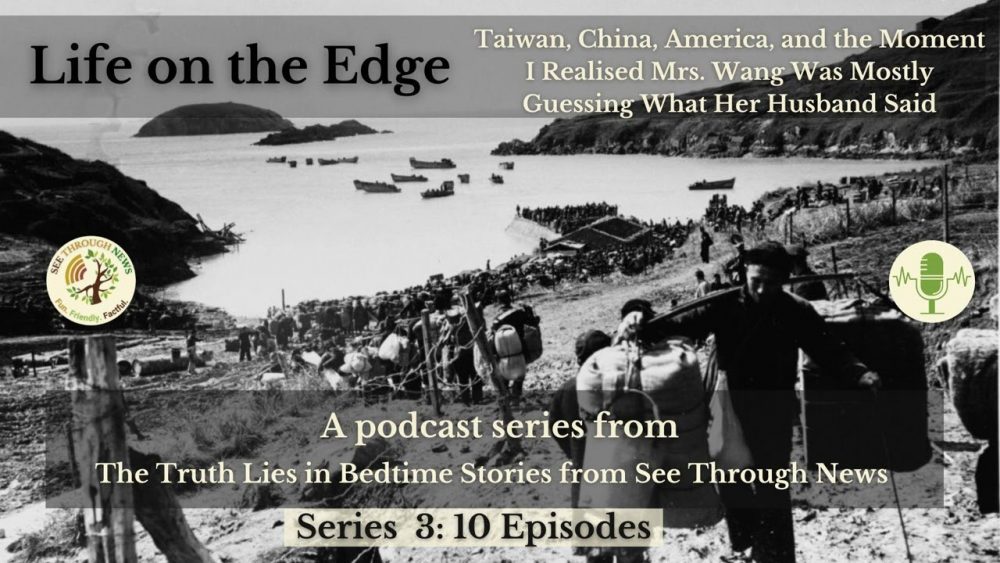

A few dozen evacuees, his fellow-passengers on the last landing craft to flee the Island, had witnessed his agonising split-second decision.

They’d joined the 18 thousand other islanders crammed aboard the 131 US Navy vessels deployed in Operation Pullback. Now, they steamed towards Taiwan, putting as much distance as possible between them and the PRC fleet on the horizon, about to liberate their now-abandoned home.

Their lives turned upside down in one morning, the evacuees started to reassemble into their family and clan units. Who was on this ship – could they see any familiar faces on the other ships?

Middle Wang, however, was alone.

There were friends and relatives who knew him well, of course, but they also knew how tight a relationship the orphaned Three Brothers Wang had had for the past 16 years.

Word soon spread. No one knew what to say to Middle Wang, sitting alone on the bare metal deck, hands covering his face.

Usually ebullient and chatty, Middle Wang remained a zombie for many days.

He remained silent, refusing all food, throughout the journey to Taiwan.

The evacuees disembarked to a mixed, and muted, reception.

You may have expected a heroes’ welcome, but they didn’t, and just as well.

You see, until it had become the Nationalist bolthole in 1949 following the Communist victory, Taiwan has itself been a backwater.

Before 1949, Taiwan was a laid-back island province on the margins of China. Its 6 million residents were a mix of ethnic groups, speaking their own dialects, minding their own business.

After defeat by the Communists, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek and more than 2 million mainland Nationalist officials, troops and others associated with his rotten regime, fled to the island-province. They said Taiwan would be their temporary base while they regrouped to take back the mainland, but the truth was, it was a rout.

By February 12th 1955, Taiwan was still struggling to cope with the influx of 2 million mainlanders, so they weren’t exactly delighted at the arrival of another fleet-ful.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek posed for a photo with the American commander of the evacuation fleet, and said something stirring, patriotic, and anti-communist.

He then despatched the Big Chen Islanders to a refugee centre, while he worked out what on earth to do with another 18 thousand people on an already crammed island.

The refugee centre was in Yilan County, which happened to be located in the northeast of Taiwan. Which was as close as you could get to Big Chen Island.

With 400 kilometres of the East China Sea between them and home, now occupied by the Communists, this proximity hardly mattered, but maybe it played its role in sparking Middle Wang’s gradual recovery.

Middle Wang takes life as it comes. He’s not the type to indulge in much self-analysis, to try to influence events, or to ponder his own actions. He’s more inclined to keep a weather eye, steer into the waves, and plot his best course. Just like his big brother did on that fateful day he set off to sell some dried squid on the mainland.

Did seeing the East China Sea every day, and thinking that this stretch of water was all that lay between him and his home and brothers, play its role in rousing Middle Wang from his slump? If he can’t say, how can we?

In any case, as the days passed, Middle Wang’s despair lifted. First he started eating again. A few more days, and he began responding to greetings. A few more and he was initiating conversations, then smiling, then laughing, then he cracked his first joke.

When Middle Wang started cooking again, his islander friends reckoned he’d be OK.

Maybe the fact that everyone else in the refugee camp was in the same position helped diminish his trauma.

None of the other 17 thousand nine hundred and ninety nine islanders had had to make quite such an impossible choice in a split second, losing a brother in the process. Now, they now all found themselves – well, not in the same boat, as fishermen they would probably have preferred that – but in the same predicament, at least.

Remember Middle Wang was only 18 years old, so was blessed with the resilience of youth.

Throughout those weeks of recovery, Middle Wang had been oblivious to the diplomatic crisis triggered by the arrival of the Big Chen Island evacuees.

As his spirit was restored, he began to follow the rumours. There was little else to do, in their Yilan County limbo, apart from cook.

There was much rumour to follow, so here’s a recap of the diplomatic timeline before and after the evacuation of Big Chen Island.

- Chairman Mao announces he’ll Liberate Big Chen Island on Feb 10th.

- Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek announces the islanders will fight to the death.

- Horrified, the US Navy scrambles to evacuate all 18,000 islanders in the nick of time.

- Chiang Kai-Shek tells the United Nations Taiwan has no space for the islanders.

- The UN scrambles to find countries looking for immigrants, like Brazil. It negotiates a relocation package that includes a bag of gold for each Islander.

- Hang on, says Chiang Kai-shek, did you say a bag of gold each? Maybe I can squeeze them in here in Taiwan after all.

And offers like that, in case you’d been wondering, is why in Washington circles the Generalissimo was known as Cash-My-Cheque…

The consequence of all this diplomacy for Middle Wang and his fellow-evacuees was that they were eventually resettled in small groups around Taiwan.

Their immediate crisis may have been resolved, but for Big Chen Islanders, being parachuted into various already-crowded communities around Taiwan was far from ideal.

As fishermen, smugglers and pirates operating from a remote island at the fringes of any jurisdiction, they’d never felt any particularly strong political affiliation to the Nationalists, or any other rulers.

And don’t forget their dialect, which no one could understand. The evacuees really may as well have been sent to Brazil, for all the mutual incomprehension they faced in their daily lives.

And Taiwan held no existing social or family ties for them. The Big Chen Islanders didn’t know anyone there, and no one in Taiwan was particularly interested in getting to know them.

If this seems heartless now, bear in mind the Taiwan they landed in wasn’t the prosperous, cohesive entity it is today.

1950s Taiwan was a chaotic melting-pot of different Chinese cultures, dialects, ethnicities and communities, living under daily fear of invasion. In 1949 their population had expanded by a third almost overnight, when those fleeing Nationalists from all over mainland China had made Taiwan their refuge.

Overlaid onto all this, the uncertainty of the emerging Cold War. No one knew how that was going to turn out. So, everyone in Taiwan already had their own problems.

This may all explain why so many Big Chen Islanders chose to leave Taiwan so quickly, once Chiang Kai-shek had cashed their cheques.

Alienation and exclusion pushed the evacuees to leave Taiwan, but there were also positive forces pulling them.

They were sailors – boats always needed experienced sailors.

Then there was America. Vast, full of empty space and opportunity, always in need of hard-working immigrants – and diplomatically well-disposed to their anti-communist ally, facing off with Red China across the Taiwan Straits.

Some evacuees emigrated directly to the United States, where they established mini Big Chen Island communities. Their dialect, common culture, and unique experience meant they stuck together, and looked out for each other.

Once the first pioneers had established a beachhead somewhere in America, it was easier for other Islanders to join them.

Across the US, often in quite random, unexpected places, not just the big port cities you might expect, little pockets of Big Chen Islanders gathered, supported each other, and found each other jobs.

Many of the jobs the islanders found themselves specialising in, involved cooking.

How and why this happened is something of a mystery. In 2015, a professor writing in the Journal of the Culinary Historians of New York tried to trace the origins of the evacuees’ association with cooking.

He couldn’t nail the exact time and place it started but here’s a quote from his article about the culinary consequences.

‘Many former residents of the Dachen Archipelago immigrated to New York in search of employment opportunities, and many of these immigrants, after learning how to cook, became highly competent chefs. Taiwanese immigrants, due to their commercial competence and ingenuity, played a pivotal role in promoting and selling Chinese cuisine, broadly defined, before the huge flood of mainland Chinese immigrants began in 1980’.

So there’s another twist to this story – these few thousand Cold War evacuees from a semi-tropical island revolutionised American Chinese food culture.

But let’s return to Middle Wang, restless in 1950s Taiwan, transplanted to his new home, but setting down no roots. Middle Wang is an energetic, optimistic, ambitious young man with itchy feet, no family to support or be supported by, and the world at his feet.

Should he join his friends signing up as crew for international shipping lines?

Should he become a chef?

Well, Middle Wang did both. He signed up to become a cargo ship cook.

For the next thirty years, Middle Wang rode the high seas, below decks in the galley, feeding the international crews of the world’s shipping vessels.

He remained resolutely monolingual, speaking only his native dialect. Big Chen Islanders travelled in packs, so he always had a few shipmates he could talk to.

For his other shipmates, Middle Wang’s shared language became food. Feeding crew from the Indian subcontinent, South East Asia, South America, Africa and Europe, Middle Wang educated them about Chinese food, and they taught him how to adapt it to their tastes.

Try to name a port Middle Wang hasn’t been to. I tried to, in that sweltering Alabama living room, when interviewing him, but failed. He may have seldom left the docked ship, let alone ventured far from it, but Mr. Wang – as I then knew him – had been everywhere: Rio, Busan, Rotterdam, Klang, Portsmouth, Yokohama, Dar Es Salaam, Aden, Galveston…

You know most of the rest of his story, and can now guess what remains.

After calling time on his sailing days, Middle Wang joined some fellow Big-Chen Islanders who’d wound up in small-town Alabama.

They found him a job in a kitchen. Mrs. Wang found a husband in him.

They settled down, raised children, enjoyed grandchildren.

Middle Wang, now Mr. Wang, loved his wife,and while he had officially retired, he still loved cooking so much, he’d often work in the kitchens of Mrs. Wang’s expanding chain of buffet restaurants for free.

But even for such a happy-go-lucky character, for his whole life Middle Wang had carried one nagging question.

What had happened to his two brothers?

In Episode 8, The Man In The Wheelchair, we find out what happened to Small Wang.