Episode 1 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News’ podcast

In Episode 1, we learn how we came to hear about this remarkable story of Cold War Theatrics, sibling relationships, and the dangers of selling dried squid, via The Wheelbarrow Question…

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 2 below.

Next: Episode 2: The Three Brothers Wang

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript:

Episode 1: A Hot Day In Alabama

I don’t want to get too hung up on the matter of Mr. and Mrs Wang’s mutual comprehension.

Remarkable though it is, it’s less interesting than the fact they were married at all.

Which is much less fascinating than how they met in the first place.

Which is way less astonishing than what Mr. Wang had been doing for the previous thirty years.

Which is way way less jaw-dropping than why Mr. Wang ended up doing that.

But still, Mr. and Mrs Wang’s mode of communication contains some very important information that you’ll need, to make sense of this incredible untold story of Cold War theatrics, sibling bonds and the unexpected consequences of selling dried squid.

Along the way, you may, as I did, learn some background on China and Taiwan that’s looking increasingly important to know, but let’s start at the beginning.

I just checked the tape, so I know the exact moment.

I wanted to establish the precise point at which I reappraised the nature of Mr. and Mrs. Wang’s relationship. As I remembered, it was when I asked Mrs. Wang to ask Mr. Wang The Wheelbarrow Question.

It happens a few minutes into the interview. Reviewing the footage, it’s more obvious now than it was at the time.

It comes when I had a question that required more meat on the bones of the amazing story Mrs. Wang had previously outlined to me about her husband’s life.

Until The Wheelbarrow Question, I’d assumed Mrs. Wang had been doing a fine job interpreting between her husband’s obscure island dialect ,and either Mandarin Chinese or English.

But then came the awkwardness.

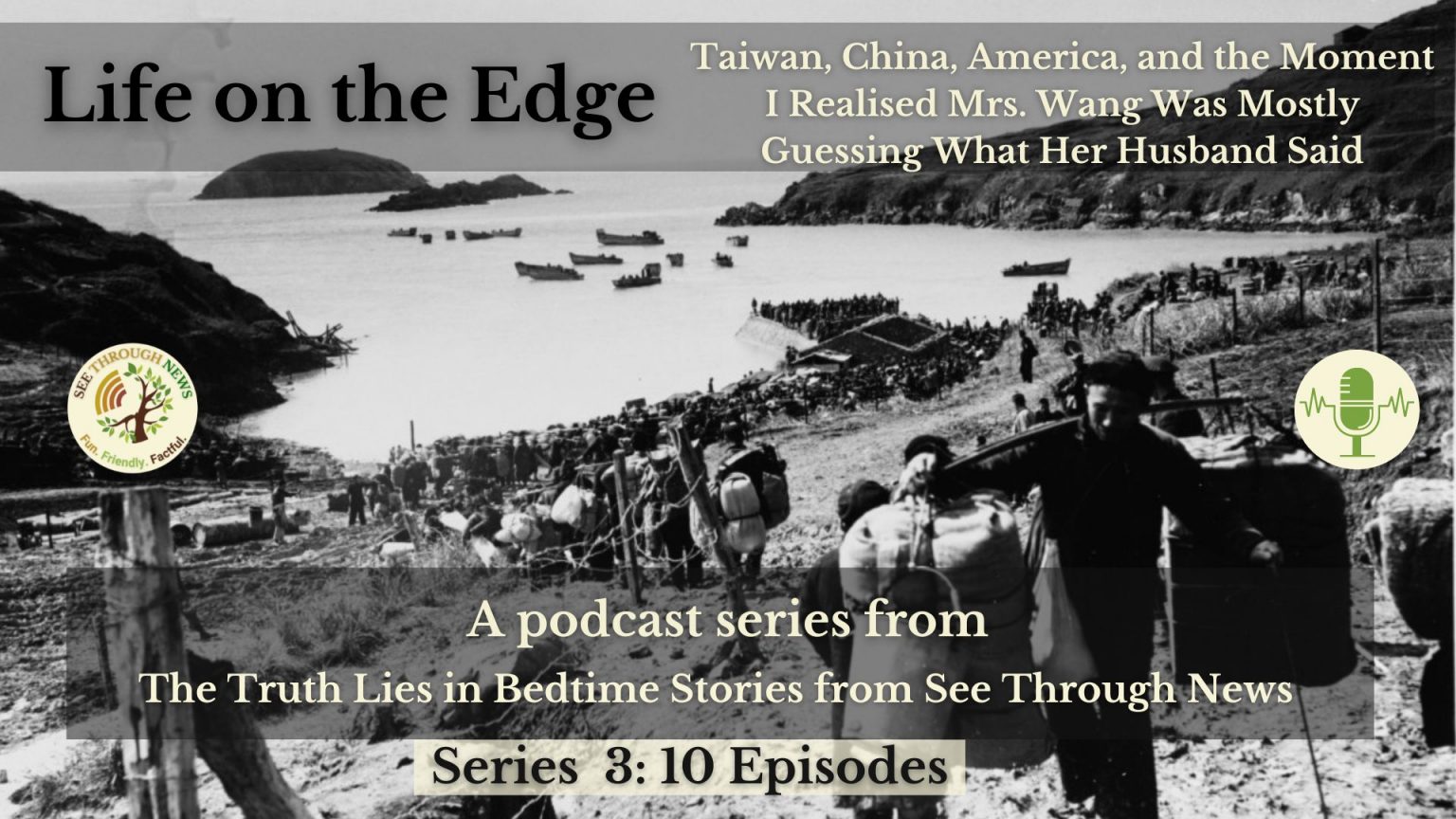

How, I asked Mrs. Wang to ask her husband, amid all the chaos of that morning in 1955, with such steep, narrow, crowded paths leading down from their village, had Mr. Wang managed to get the wheelbarrow containing his paralysed little brother as far as the beach?

For reasons I’ll explain, Mrs. Wang was sitting behind me, so as the awkward silence extended, her demeanour provided no hint of the tricky situation I’d put her in.

I could barely follow the Hangzhou dialect she used to talk to Mr. Wang, her husband of 30 years.

I had still less of a clue about the island dialect Mr. Wang used in reply.

Her translation of The Wheelbarrow Question had taken a bit longer to pose, and sounded less fluent and assertive. But it was only when I saw Mr. Wang’s deepening furrowed brow of incomprehension, that it hit me.

Mrs. Wang’s ability to communicate with Mr. Wang was, I suddenly realised, something less than ideal.

My Mandarin Chinese is OK, but when it came to this impromptu interview, I might as well have not spoken it at all.

Mr. Wang, though blessed with an exceptionally friendly and warm personality, spoke only his native island dialect.

Technically, it was a dialect of Chinese, but a Glaswegian conversing with a Sicillian would understand each other better than Mr. Wang and I. He was diplomatic enough to pretend to understand my Mandarin, and until The Wheelbarrow Question, body language had served our purposes absolutely fine.

Nearly all our interactions had been related to his cooking, and how delicious it was, which works fine in pantomime.

It was only when I’d asked if Mr. Wang would mind me recording his life story that the need for some more effective communication had arisen. That, was why Mrs. Wang had offered her services as interpreter for the video interview I was conducting when I got to The Wheelbarrow Question.

The content of Mr. Wang’s stuttering response was as impenetrable to me as every other word I’d ever heard him utter, but even I could tell that:

- He’d got the wrong end of the stick

- Mrs. Wang had no idea of the end of the stick that he’d got

So that’s how we’d arrived at this delicate situation. It’s all there on the tape.

- Mr. Wang struggling to understand his wife’s question.

- Mrs. Wang struggling to finesse her issues with transmitting my question and his reply.

- Me struggling to work out how to save everyone’s face, but still winkle out the story I was trying to uncover.

On the tape, during this awkward gap, you can hear the ceiling fan. I remember it barely stirred the hot, viscous August air of their suburban Alabama living room.

Some diplomatic rephrasing of the question and a bit more pantomime, and the interview got back on track.

But THAT, was the moment I realised Mrs. Wang was mostly guessing what her husband said.

Sure, they were educated guesses. The more they’d spoken about a topic before, the more reliable her interpretations were, but from that moment on in the interview, I started phrasing my questions more carefully, and using more gestures, to avoid further embarrassment.

After that sticky patch, the rest of the interview went fine. I ended up with a reasonably comprehensive version of Mr. Wang’s life story, on the record.

Most of us like being asked about ourselves, but imagine how you’d feel if, after 40 years of not understanding and not being understood, you’d finally got the chance to tell your life story.

Mr. Wang made up for the limits of his verbal communication with his great natural ebullience and enthusiasm, usually expressed via the medium of food.

Whenever I showed up, he’d already have his apron on, and be hovering by the kitchen door. My appearance at the front door would be his cue to give a cheery wave of greeting, sharpen his chopper, open the fridge and start cooking something delicious, while I chatted to his wife. After thirty years as a ship’s cook, and fifteen as a chef in Chinese restaurants in Alabama, Mr. Wang’s universal language was food.

After hearing about his life story in dribs and drabs, I called Mrs. Wang to ask if he’d mind me recording him telling it. Before she could relay his response, I could tell from his muffled bellow of delight he was up for it.

When he opened the door that day, it was the first time I’d ever seen him without his apron on. He’d put on some smart clothes, a tie even, and was beaming even more broadly than usual.

I set up the camera between two chairs in the living room, and invited him to sit opposite me while I faffed about with microphones, lighting and framing.

As I did so, he kept up his staccato barrage of conversation with his wife, not a word of which I understood. I couldn’t stop smiling at the contrast between Mr. Wang’s beaming face and the string of impenetrable sharp barks that tumbled from it.

I asked Mrs. Wang to sit behind me, rather than next to me. This caused a bit of confusion, before I explained to her, and she to Mr. Wang, this would keep Mr. Wang’s eyeline constant.

Most interviewees instinctively look at the interpreter rather than the questioner. If we sit side by side, I explained to Mrs. Wang, and she to Mr. Wang, her husband’s eyes would constantly be flitting between us. What felt polite to him, ends up looking shifty on camera.

Mrs. Wang appeared to successfully convey this TV journalist’s trick of the trade to her husband, as he was soon nodding, grinning and giving me the thumbs-up as his wife settled down behind me, peeking around my right ear.

As I overheard them conversing, while testing sound levels, I reflected again what an odd, but well-matched couple they were. Mrs. Wang was educated – not many Chinese women of her era had been to university like her. Mr. Wang, was barely literate.

They’d met when she’d hired him at her Chinese buffet restaurant, and were married within a year. This boss/worker relationship, overlaid onto traditional Chinese patriarchal power balances, and transplanted to conservative Alabama in relatively liberal America, made for a potentially complex cocktail of status imbalances.

But I’d never seen any sign this bothered either of them in the slightest. Mr and Mrs Wang treated each other with great deference, affection, and consideration. I’d never seen them argue, and their mutual love was visible in their every interaction.

The matter of their language of communication had always intrigued me, but I’d just taken Mrs Wang’s explanation at face value. She’d told me her native Hangzhou dialect wasn’t a million miles from his peculiar island dialect, and that she’d picked up some of her husband’s words.

Mr. Wang, by contrast, remained resistant to speaking anything other than his mother tongue.

Now in his 60s, he’d left his native island at the age of 18. In the half century since, he hadn’t picked up more than a few words of any other language.

It was a tribute to Mr. Wang’s other life skills that he’d not only survived, but made his journey from last-minute Cold War evacuee to comfortable suburban Alabama retiree without anyone other than his few thousand fellow-islanders properly understanding the noises that emanated from his wrinkled, tanned, sailor’s face.

What I’d heard from Mrs. Wang about his amazing life story, and the equally extraordinary stories of his two brothers, was enough to prompt me to get it on record.

So far as I could tell, no one else had yet done so.

I’d looked. Libraries had turned up nothing.

Online, I’d trawled through some retired US Navy veteran forums. I’d found a few eyewitness accounts of this amazing episode of Cold War history.

For the US Pacific Fleet, the 1955 event that turned the lives of Mr. Wang and his two brothers upside down was one of their proudest, finest – though most under-reported – hours.

So there was a bit on the record about the rescuers, and their heroic, but relatively minor role.

I trawled the internet for anything reflecting the perspective of Mr. Wang and his few thousand fellow-islanders, but found nothing.

Given the islanders only numbered 18 thousand, this was plausible. Given even Chinese people from a couple of hundred miles away, who’d been married to them for decades, couldn’t understand their dialect, it was unsurprising.

My impulse to put the remarkable story of Mr. Wang and his two brothers on the record, was the reason the three of us – me, Mr. Wang and Mrs Wang sitting behind me, were slowly baking in an Alabama living room at the turn of the millennium, and how I came to ask The Wheelbarrow Question.

Over the past two decades, I’ve tried to interest broadcasters in this amazing story, but not one of them bit. There’s still hardly anything about it on the Internet.

That’s why, nearly two decades later, I’m finally getting round to telling the story of Big Wang, Middle Wang, and Small Wang, and putting it out there for you to find.

In Episode 2, The Three Brothers Wang, Mr. Wang, via Mrs. Wang, tells us the extraordinary circumstances under which he left a perfectly good breakfast on the kitchen stove, in order not to become communist.