Have a plan, be ready to change the plan – our recipe for effective and efficient video production

- This article is part of a series of linked articles See Through News used to train its volunteer citizen journalists in how to create high quality video reports on zero budget.

- Our Global Reporter Intensive Training (GRIT) programme is designed for complete novices of all ages. Trainees require no more than a smartphone and internet access.

- GRIT is suitable for self-study or for use in groups, and like all See Through News resources are open source and free to use (but please acknowledge See Through News if you do).

Here’ our suggested sequence to read these GRIT articles:

- GRIT User’s Guide: an overview of the course and how you can use it

- How To Tell Video Stories: visual storytelling basics

- Free Carbon Drawdown Activisation Resources: some ideas to stimulate your ideas

- How To Plan A Video: (this article) for video, as for life, good preparation saves time and frustration

- How To Shoot A Video: 3 Rules: basics for acquiring good images and sound

- How To Edit A Video: 5 Steps: basics for clear visual storytelling

Planning, and what a producer does

No matter the scale of your production, whether you’re making social media memes, news reports, or Hollywood movies, the basics of visual storytelling are the same.

Nowhere is this more true than in the ‘Producer’ role, the hardest to define, and most critical role of all. It explains why in the credits to big TV series or movies there are so many different people credited with some kind of ‘producer’ title.

Makes sense, all products need a producer, and a news report is a product.

This article outlines the basics. All successful productions follow most of these rules. Most unsuccessful ones fail because they break one or more.

Key Video Production roles

There are 5 critical roles to audio-visual storytelling.

It’s possible for one person to perform all roles, or for them to be subdivided into many sub-roles, but it’s useful to consider them separately. Even for solo video production or multi-tasking, being conscious of which hat you’re wearing at any given moment is good practice.

These are the 5 key jobs in any video production.

Director/Reporter:

- You are in overall charge. Good leaders listen, but one person has to have the final say, and it’s you.

- You’re the person who does the interviews, reports on camera, makes the big creative choices, and so you bear ultimate editorial responsibility for the video.

- You must be particularly well prepared, able to answer any questions about your video’s content and appearance, and a good leader. Appear relaxed, even if you’re feeling nervous or stressed. This relaxes your crew and your interviewees, who will all perform better if you inspire confidence.

- Use the RON checklist before you do an interview. Are you Relaxed, asking Open questions, and Nodding?

Camera operator:

- You are responsible for the images.

- You’re focused on how the video looks.

- You must have lots of practice using your camera, whether its a fancy one or a smartphone, and know how to your equipment.

- Use the BALES checklist before you do an interview. Did you check Battery & storage space, Aspect, Lighting, Eyeline and Steadiness?

- Have a Sequence checklist if you’re filming anything else – will you give the Editor enough options to tell the story?

Sound recordist:

- You are responsible for the sound.

- You’re focused on having as little background noise as possible, so we can hear clearly.

- You must be alert to any distracting noise, like bumping the microphone, engines running in the background, people talking, babies crying, dogs barking, a plane passing overhead etc.

- If it’s too noisy, and there’s something that can be done about it (moving somewhere quieter, waiting for the noise to stop, removing the source of noise etc.), it’s your job to alert the director/camera operator.

- Use the HEP checklist before you record. Is there Hush, is there Elbow Room around the camera, and Proximity – are you close enough to record clear audio?

Editor:

- You are responsible for deciding which parts of the interview to use, what order to put them in, what text to put on the screen, and what additional sound or music to add.

- You pay very close attention to what’s recorded on the camera – if it’s not recorded, it might as well not have happened.

- You must be very fussy about what is recorded, because you want to avoid mistakes before you have to edit the material, by which time it’s too late to fix!

- Study the 5 Steps checklist to make your editing job as easy as possible.

Producer:

- You are responsible for everything apart from what the Reporter, Camera operator, Sound Recordist, and Editor do – you decide what you’ll film, who you’ll interview, you make sure everyone is at the right place at the right time, and deal with problems as they arise.

- You always have a plan, but are always able to change your plan as the situation changes.

- You are an excellent communicator, informing everyone of what they need to know as early and clearly as possible, and promptly alerting changes of plan to everyone who needs to know.

- You are the person who enables everything to happen, gets things done in time and on budget, and meets deadlines.

- Read all the GRIT articles carefully, so you know everyone’s job.

Research

We won’t go into much detail about how to research, as what story you want to tell is up to you.

If you agree with the See Through News Goal of persuading people to measurably reducing carbon, however, we’ve compiled some thought-provoking resources in our Free Carbon Drawdown Activisation Resources article.

It lists various articles and videos from the See Through News website, and YouTube channel, categorised by carbon-emitting sector. There is of course plenty of other information available on the issue of net zero, and carbon reduction.

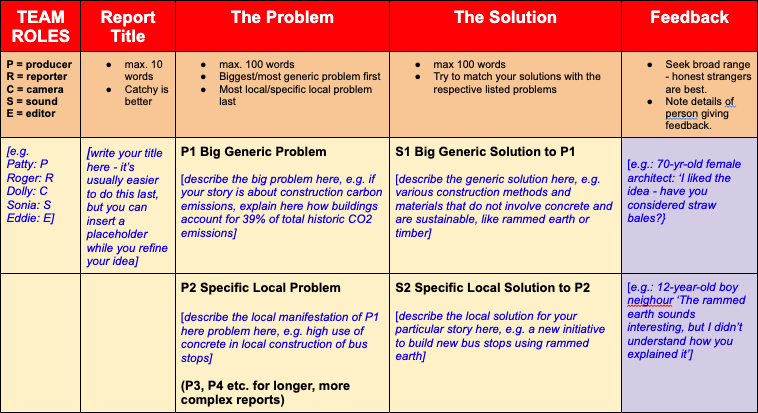

Story Idea – GRIT template for short reports

For 2-4 minutes news-style reports on a single issue, GRIT has drawn up this basic template, which you can download for free.

We hope it’s self-explanatory. It’s very simple, and you may need more sophisticated ways of describing your video as you get more experienced (see below), but this basic template will always work.

Try reverse-engineering news reports you see, using this template (i.e. filling in the form based on a report you see, rather than your own research). You should find that most TV news reports can be analysed in this way.

Story Idea – Treatment template for longer videos

‘Treatments’ are used by professional visual storytellers to sell their ideas. Vast amount of research and in-depth access negotiation are distilled down to a single page of A4, a super-condensed version of your grand vision.

Even if no one is paying your to make your video, the discipline required to boil you idea down to a page is well worth doing. Indeed, making and funding a video entirely solo is a very good reason for subjecting your idea to the kind of robust interrogation that writing a Treatment demands.

Your Video On One Page

A Treatment is your key tool for convincing someone to accept your proposal for film. Writing a good treatment is a critical first step in turning an idea into a film. It:

- Focuses your thoughts, your aims and your creative goals

- Helps you plan how to realise your vision

- Makes you think carefully and realistically about how to achieve the film you want

- Convinces gatekeepers/funders that you know what you’re doing

What’s a Treatment For?

A treatment is the usual tool to pitch to a commissioning editor, or to apply for entry into a festival or competition. It has 2 basic aims:

1) to convince your potential audience. At this stage that is actually who is anyone reading your treatment (who might be a commissioning editor, or part of a funding body or other panel or editorial board) that your story is worth telling and that they and other viewers are going to get a lot out of watching the way you are telling that story

2) to provide yourself with a framework from which to think and plan your project from pre- to post-production.

What Does A Treatment Look Like?

Many stories are worth hearing, but good ones are all about the way you tell ‘em. What follows is not the only way to do it, but a useful format to order your thoughts, and plan ahead..

Sometimes, whoever you’re pitching to will have a set format to follow. These usually require you to fill in the following fields:

- TITLE

- DURATION

- PROJECT NAME

- DIRECTOR & PRODUCER NAMES

- WHERE THE FILM WILL SHOWN

Your treatment should run to a single page, broken into 4 segments.

1 Treatment Heading (the “Slate”)

This is the header at the top of the treatment you present. It contains what might go on the slate clapped in front of the camera on set or location to mark the takes.

It’s very useful information. Thinking about a working title at this stage helps focus your mind on your narrative. What film are you making? What’s it going to be called?

The same goes for fixing your film’s duration.

2 The Story

Half a page, max. A tightly-told précis laying out your narrative.

In 2-3 short paragraphs, describe the story you’re going to be presenting on screen. Discipline yourself to work with this restricted framework. You need to tell a compelling tale, but in only slightly more space than a Tweet. Think haiku, not novel.

Introduce the focus of your film: a person, a place, an incident, something more abstract? How you approach your narrative is the filmmaker’s choice.

If appropriate, include facts & figures. These can give structure and meaning to the narrative. If you intend to present your story in an offbeat way – mixing images, playing with a colour grades or sound in postproduction – state it clearly in this segment.

Your story might be highly personal, all about your own responses to the activities of the group, community or place you’re depicting.

Or it might be a straightforward factual documentary. However you approach it, this segment is your chance to lay out what your films about.

As I know you’ve all been doing, now is the time to really familiarise yourself with the charity you’ll be making a film about. All of them have plenty of resources online, that will help steer your research and educate yourself about them and their aims and activities. You may find information about an activity or a key person connected to the charity that particularly inspires the direction your treatment takes. Any research you do or meetings you might be able to have with people involved in your charity will provide further inspiration and material.

3 The Key Elements

No more than 3-4 lines.

This is where you introduce some of the key elements found in the film, e.g.:

The story of X will be told through the life of XXX XXX , one of the project’s originators. We see how their involvement has transformed their own lives, their community’s possibilities, and their connection to their local community.

There’s no better guide to X House than XXX XXX – he’s lived all his life in its shadow. He played there as a kid, hung out in its gardens as a teenager, became its caretaker in 2007, and is now general manager for this very public property. XXX alone knows how it’s been rocked by funding cuts and vandalism – and how the local community has responded by taking things into their own hands.

4 Creative and Technical Approach

No more than a short paragraph at the end of the page.

What kind of film will you make, and how will you make it?

What genre: documentary? a promo-style video? a conceptual or poetic exploration?

Will you be combining archive and original material? Mainly interviews? More than one camera platforms?

Good Luck, but Improve Your Chances

If you’re asking someone to give you money to make your film, take time to understand and adapt to their particular requirements.

But they’re also looking for filmmakers with a strong sense of style and identity.

Think about what you want your film to be.

Being realistic doesn’t mean you can’t aim high.

Why do factual videos need scripts?

Real life is often said to be ‘following a Hollywood movie script’. The raw material of factual videos, like news reports and documentaries, consists of verifiable fact, and not fantasy, but these ingredients are cooked using the same storytelling tricks and structures.

That’s why even simple news reports have ‘scripts’, whether in the form of a Treatment, production schedule, or formal ‘shooting script’, even before any filming begins.

Those unfamiliar with visual storytelling can misunderstand the purpose of a factual script. They see having a script, complete with quotes from interviews not yet conducted, as evidence of Fake News, or a sinister manipulation based on some predetermined ‘agenda’.

This can be true of bad, unethical journalism, and it’s a slippery slope from good professional practice to Fake News, but few would accuse scientists of ‘Fake Science’, simply because they form a hypothesis before conducting research.

For factual videos, a pre-shooting draft script, or Treatment, is simply a hypothesis, an argument to be tested against reality. Like scientists, journalists have to start out with some kind of plan. Like scientists, their experience, education and research may determine the quality of their plan, but it’s still just a plan.

And like scientists, journalists should be prepared to change their hypothesis, and alter their plan, as they start their experimentation, or shooting. Good journalists change their plans, and their scripts, as they ‘re tested by the real world. Bad journalists, like bad scientists, are so wedded to their pre-conceived idea of the story they want to tell, they ignore inconvenient truths because they don’t ‘fit the script’.

Movies bend reality for their story. Factual videos should be shaped by reality. That’s the difference, but both require scripts as a starting point, updated as time moves on and reality bites. Even Hollywood scripts aren’t ‘carved in stone’ – drafts are updated right until the last tweaks are completed.

Be wary of any video that doesn’t start with a script. Be very wary of any factual video that ends up with the same script it started with.

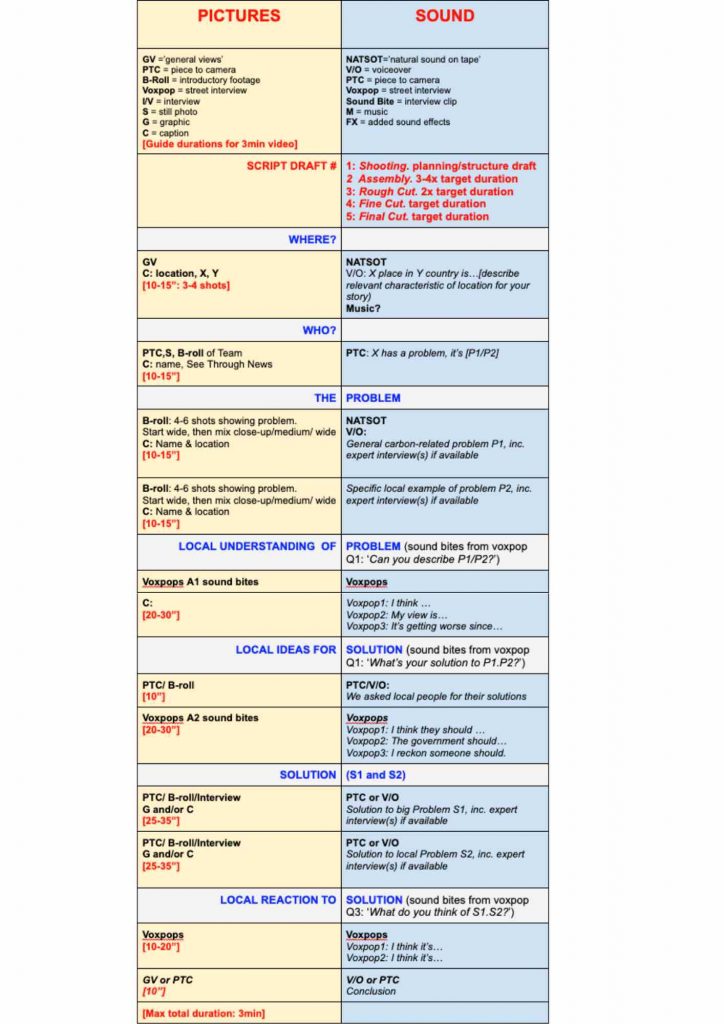

What does a script look like?

A script is a visual storytelling plan. It comes in many forms, but here’s a very basic one created for the GRIT course. It’s a good starting point for any visual story, and provides a solid scaffolding from which to work, and foundation on which to build.

Eyes & Ears Ingredients

The two columns show which of two types of ingredients you’re planning to combine at each step of your story.

As an audio-visual medium, these two categories are:

- Pictures: what your eyes see at any given point in your video

- Sound: what your ears hear at that same given point in your video

It really doesn’t matter which ‘comes first’. Convention usually places pictures on the left, and sound on the right, but this is a matter of personal preference. Some editors start with audio, and add pictures. Others start with pictures, and add audio. There’s not right or wrong way. Once you start refining your first draft, it no longer matters, as the process of editing is one of constant adjusting how Pictures and Sound complement each other to best serve your story.

Beneath the Picture and Sound column headings, our script template has a handy key. For expanded descriptions of what a Piece To Camera, NATSOT etc. mean, see our article How To Edit a Video.

Shooting, Assembly, Rough Cut, Fine Cut, Final Cut

Even for short, quick turnaround news reports, scripts can go through many revisions. Hollywood movies can have dozens of re-writes before they even find a director.

Refining, trimming, tweaking, or even complete tear-it-up-and-start-again restructuring, are an essential part of the visual storytellng process. This is actually where most of the storytelling happens. This is the alchemy, the cooking, the recipe.

Video making is best done collaboratively, but as we mentioned at the start of this article, clarity of thought and communication are just as important if you’re doing all the jobs yourself.

There are five basic stages to editing, each of which should, at least notionally, have it own script version.

Shooting Script 1

Your initial plan, based on your story idea /treatment document. It basically translates your static, text-based description of your vision into a dynamic, linear, version, detailing what the view will see and hear at any given point. A Shooting Script is not set in stone, and may end up being very different from your final version, but it clearly expresses your initial hypothesis in a form all of your production crew, from camera operator to editor, can understand. Now seek feedback (see below).

Assembly Script 2

The Assembly script is your first attempt to put what you actually filmed on a timeline after shooting. Now your vision has encountered reality, your assembly edit reveals not what you thought you might get, but what you actually have. Don’t bother too much about duration at this point – just prune away all the bits you definitely won’t use (like flubbed PTCs, useless interview answers, wobbly shots, multiple takes of the same thing etc.). Arrange them on the timeline roughly according to your original structure. The duration may be several times your target. Now seek feedback (see below).

Rough Cut Script 3

The Rough Cut is a more refined version, where after seeking internal and external feedback, you start to both trim down the options, and review the sequence in which you tell your story. A Rough Cut should be no more than twice your target duration, ideally more like 50% longer. Now seek feedback (see below).

Fine Cut Script 4

The Fine Cut is exactly the same duration as your target, including any opening and closing titles/credits. You have yet to do any final polishing, like colour-correcting the pictures or doing a final mix of the audio. Your story should now be approaching its final form, but can still change radically, often replacing sequences with previously discarded ones. Fix the pictures before you record the final narration, as it’s easier to tweak words than unpick a timeline. Now seek feedback (see below).

Final Cut Script 5

The Final Cut script describes your final product, the one the public will see. It’s the ultimate reference for all the last-minute polishing of picture and sound. No more tweaking – your next feedback with be the public response

Feedback Top Tips

Every story needs an audience, and every storyteller has to tailor their story for their particular audience.

Video storytelling has its own challenges. Tell a story live around a campfire or in a lecture room, and you can ‘read the room’, and adjust your story on the fly. When you edit a video, you’re guessing how your audience might react, so the more you test it on people and gauge their ‘live’ reaction, the better your video will become.

Seek our honest strangers

Your most valuable resource is an honest stranger, a critic who knows nothing about your video, and gives frank feedback.

At every stage of your edit – Assembly, Rough Cut, Fine Cut, Picture Lock, or final version (see How To Edit A Video for details) – getting honest feedback from someone seeing your video for the first time is invaluable.

How to learn from honest strangers

Once you’ve convinced someone to help you with their reaction to your current edit, observe them as they watch it.

- When do they pay attention, laugh, weep, whoop and express amazement?

- When do they frown, look confused, fidget, get bored, start looking at their phones?

After they’ve watched it, explain how the least helpful thing they can do is to be polite, and the most helpful thing is to be brutally honest.

Then ask them an open question (see How To Shoot An Interview for the difference between an open and closed question) like ‘What did you think?

- Listen carefully to their feedback. Note what they liked, and keep that in. Note what they didn’t like, or didn’t understand, and find a way to fix it. Note what questions they have, and try to answer them in your revised version.

- Resist the urge to explain. If they didn’t understand your point or follow your story, that’s your fault, not theirs.

- Know when to stop. Deadlines and sanity mean there’s a limit to how much attention you pay to the opinion of others – it’s your story, and up to you how to tell it. But learning how to make the most of honest strangers is an important part of any storytelling process.

Script Top Tips

Every video, whether a blockbuster movie, a music video or a 2 minute news report, depends on a good script.

No one writes a perfect script first time. You need to go through many drafts, each one eliminating faults and adding improvements, before you ‘get it right’.

Not that there’s such a thing as a perfect script, only the best script within the budget and by the deadline.

The best way to learn is to do, and work out what works for yourself, but following these hints will save yourself a lot of time and avoidable frustration.

Writing for the ear v. writing for the eye

When we read, we can go at our own pace, scan, skim and skip back and forth.

When we watch a video or listen to a podcast, we only have one chance to hear and understand. This means you have to write for video in a far more clear and compact way.

75 WPM

This video explains why 75 words per minute is optimum speed for voice overs.

This means that for a 3-minute video, you entire spoken script, including sound bites, and ‘breathing spaces’ for NATSOT, should be no more than 225 words.

This means you have to make each word count. Focus on the most critical, logical and powerful elements of your story.

Resist the urge to cram words in – it’s never worth sacrificing less clarity for more content.

Avoid Unnecessary Repetition

With a limited word budget, you can’t afford to repeat things, unless you have a good reason.

Subtitles apart, avoid repeating exactly what you’re saying in the captions. Why say your name if the audience is reading it on the screen?

There’s no need to describe exactly what you’re seeing in the pictures – that’s for radio.

Treat each word, and pause, as a precious resource, and squeeze the maximum benefit from them.

A picture is worth 1,000 words

A good test of the clarity of your storytelling is whether a stranger can make sense of it with the sound off. A good video is comprehensible with the sound muted.

Images can carry a huge amount of information that you don’t need to repeat or describe in the script. A good 15”, 3-shot GV opening sequence can tell the viewer more than a page of dense statistics. This is the power of images.

Can it work as a radio report?

Similarly, a good test of your storytelling is whether a stranger can understand your story from the sound only.

Making your video work as a radio piece means you’re using all the senses in an audio-visual medium. You don’t always have to use all your audio ingredients listed in How To Edit A Video: 5 Steps, but it’s always worth considering them:

- NATSOT

- V/O

- Actuality

- Sound Bite, AKA interview clip

- Music

- FX