Episode 2 of Life on the Edge: Taiwan, China, America, and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said, Series 3 of our ‘The Truth Lies in Bedtimes Stories from See Through News’ podcast

In Episode 2, we learn about the early lives of Big Wang, Middle Wang, and Small Wang, and get to know their remote island home, 400km north of Taiwan.

For best results, start at the beginning: Episode 1: A Hot Day in Alabama

If you’d like to listen to the 10 episodes one by one, like chapters in a bedtime story, click the link to Episode 3 below.

If you’d prefer to hear the whole story in one go, here’s the omnibus edition.

Next, Episode 3: A Morning of Comings and Goings

Written, Produced & Narrated by SternWriter

Audio Production by Rupert Kirkham

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

Transcript:

Episode 2: The Three Brothers Wang

There was a lot to contend with: the Alabama heat, the clunky translation, the passage of half a century, an interviewee who had little formal education and wasn’t used to communicating via any means other than food.

Yet, twenty years after he told it to me, Mr. Wang’s story remains as unexpected, astonishing and gripping as it was on that sultry Alabama summer’s day.

The man I’ve so far called Mr. Wang grew up as Middle Wang, or at least, he did after his younger brother was born.

Two years separated Middle Wang from his elder brother, known as Big Wang, and from his younger brother, known as – yup – Small Wang.

They were born in the 1930s on an island in the East China Sea about halfway between Shanghai and the mainland port of Fuzhou, if that means anything to you.

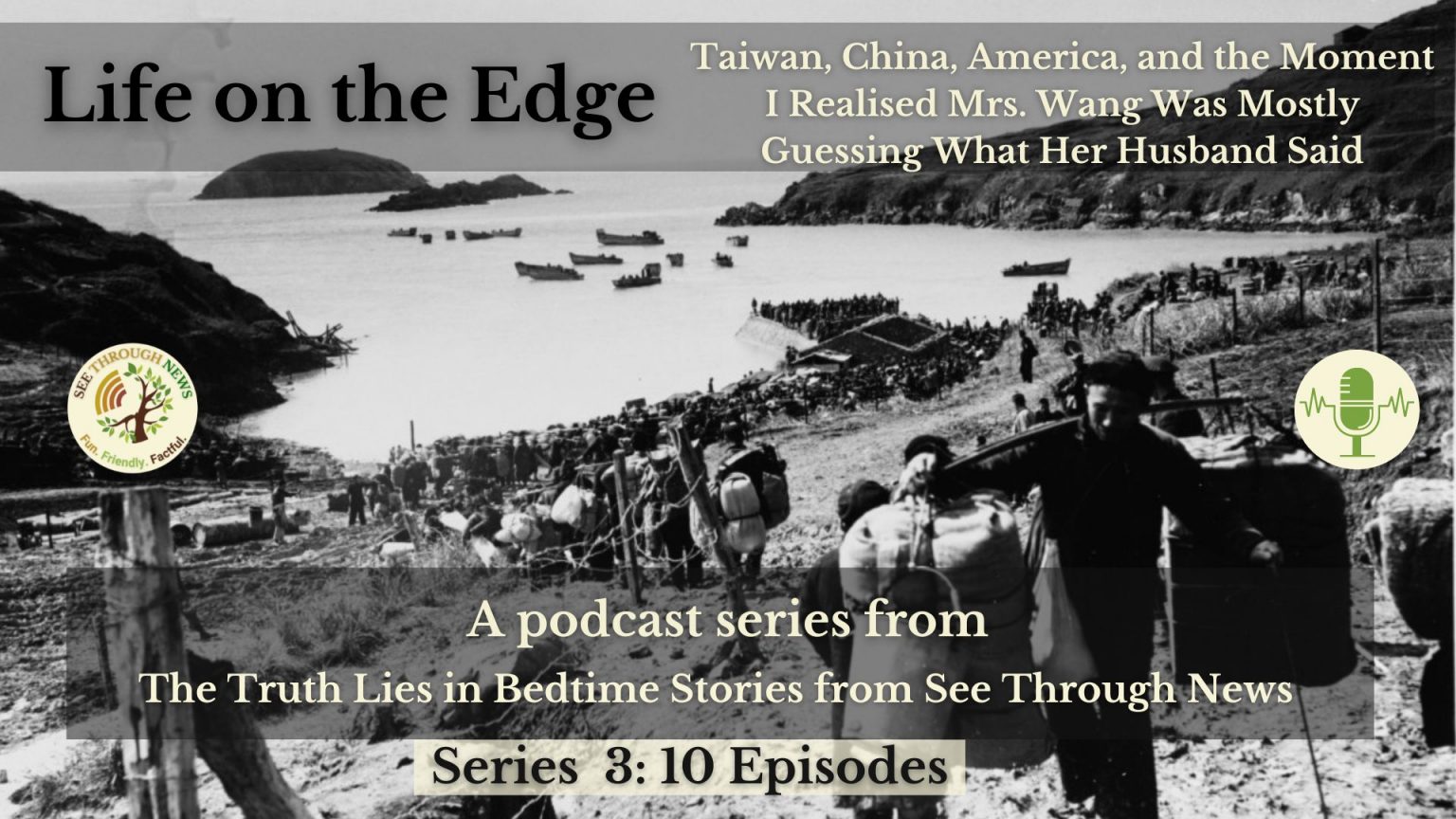

The island was called Big Chen Island – Da Chen Dao. It was part of a group of a couple of dozen islands, but only a couple of them had significant populations.

Big Chen Island is around 20 kilometres from the Chinese mainland. Not a huge distance. Not a trivial one either.

Far enough that the 18,000 islanders have always had to be pretty self-sufficient, and the Brothers Wang grew up during a particularly chaotic period. Born into the chaos of warlord factionalism and the emerging communist peasant movement, China then experienced Japanese occupation, the Second World War, and then civil war between the Communists and Nationalists.

In many ways, a small subtropical island of no great strategic importance was a rather good place to grow up when China was in such turmoil.

Life on the margins has its advantages, especially if you’re quite happy for no one to pay close attention to what you’re up to.

Officially, the islanders subsisted on fishing. Unofficially, their sailing skills were not unhelpful in pursuit of other…’traditional trades’ that, in the views of some, might cross the line into the realm of the illegal.

Piracy and smuggling are words used by the powerful to prevent people on the edge of society from threatening the status quo. When the status quo was as chaotic as it was in China in the 1930s and 40s, the islanders of Big Chen Island might have been forgiven the odd legal transgression, as they sought their own ways to survive.

Being so few in number, on such a small island, not on the way to anywhere, the Big Chen islanders threatened no one. As they had been for centuries, they were pretty much left to their own devices. They also made a point of avoiding interfering with anyone else’s devices, apart from a bit of low-level piracy, and selling their contraband home-distilled sorghum liquor without troubling the tax-collectors.

Maybe that’s how they developed such a strong dialect. When you’re minding your own business, twenty miles of open sea may as well be a thousand.

This remote, but far from unpleasant, island life was what the Brothers Wang grew up with: bit of farming, a bit of fishing, a bit of – ahem – ‘maritime trade’. This was how Big Wang spent his first 20 years, Middle Wang’ his first 18 years, and Small Wang his first 16 years.

It’s easy to paint this as too idyllic, of course. Life on the edge is tough. Mothers routinely died in childbirth, like the brothers’ mother had after delivering Small Wang. Fathers would set out fishing, and one day never return, like theirs had eight years later.

Typhoons could sink ships at sea, and destroy houses on land.

The Industrial Revolution had barely made it as far as Big Chen Island. They lived a subsistence lifestyle, with radiating circles of dependence on close family, clan units, and their island community. Chinese often use the saying ‘ the mountains are high and the emperor is far away’ to explain how local practices can diverge from official policy. Twenty miles of open sea, it turns out, can be just as effective a barrier to governance as a mountain range.

On Big Chen Island, children were expected to work as soon as they were able. That was why Small Wang joined his uncles and brothers out on the family fishing boat at the age of 10. That was how, when he didn’t avoid the boom in time, Small Wang had become paralysed, paraplegic. Ever since, his family had cared for him.

They couldn’t leave Small Wang alone, and had to take him wherever they went, whether tending their fields onshore, or fishing at sea.

The only practical way to transport Small Wang up and down the steep, narrow paths from their stone cottage to their boats on the beach, was in a wooden wheelbarrow.

They performed what became known as The Butt-Kissing Move dozens of times a day, so often they barely needed to look at each other while executing it.

Each brother would grab one of Small Wang’s limp hands, plunge his head below one of his limp arms, and grab one of his limp legs. When they stood up, Small Wang would be folded over their strong shoulders. It happened in a flash, and The Butt-Kissing Move became a well-known entertainment on Big Chen Island.

The brothers would sometimes play to the crowd, joking about the position they now found themselves in. The big brothers would say there was really no need for Small Wang to kiss their arses to thank them, and Small Wang would complain about smells emanting from where his nose had ended up.

Maybe because sudden, out-of-the-blue disaster was part of everyday life in pre-war China, maybe because of the support of his tight-knit family and island community, or maybe because he was just that kind of 10-year-old, Small Wang bore his paraplegia lightly.

Denied any physical movement of his four limbs, Small Wang made the most of his ears, tongue and brain. He was curious, quick to learn, and memorised everything.

Small Wang was in a constant state of conversation, listening as much as he spoke, and interacting with everyone he met. On a small island, that was almost literally everyone.

By the time of the events of this story, Small Wang, now 16 years old, not only knew everyone on the island, but had become known by them as a repository of information about everything that happened on their island.

People would borrow him, wheeling him to their homes to exchange the latest gossip, and – as he grew older – seek his opinion.

Thus, did Small Wang become Big Chen Island’s portable oracle, and mobile library.

Middle Wang was a younger version of the same character you met in Episode 1. As a young man, he had the same sunny outlook, enthusiasm and work ethic he displayed when I got to know him, in suburban Alabama, towards the end of his life.

He started early as a chef. With no mother, and then no father, Middle Wang took on the cooking duties, and enjoyed them. He was always first up to get the fire going and start cooking the breakfast rice porridge, and preparing tasty side dishes. These were usually pickled vegetables he’d cultivated himself in the family’s fields down the slope from their front door, combining vegetables like asparagus lettuce with favourite herbs, like nine-story-pagoda basil.

Middle Wang was increasingly taking on the work tasks done by the eldest, as Big Wang began to spend more time away from the island.

At twenty, Big Wang had his own cargo boat. He’d sail it to the mainland to trade dried fish for goods they couldn’t make on the island, or pick up cash, doing delivery odd-jobs for the merchants of Taizhou and Wenzhou.

Big Wang would sometimes disappear for weeks at a time. They’d only know he was back when they saw his boat approaching the little harbour. Big Chen Island had no radio mast or receiver, so news only arrived in person, or by word of mouth. This was why Small Wang, wheeled from house to house, played such an important role in Big Chen Island life. He was their local search engine, switchboard, reporter and broadcaster.

So it was that Big Wang was not on the island on February 10th 1955.

Middle Wang and Small Wang were sorry their big brother hadn’t been around for the Spring Festival celebrations. The lunar New Year feasting had began on January 24th that year.

A couple of months before, they’d waved goodbye to Big Wang in his little boat, laden with dried squid, and hopes of making money from some odd-jobs once he’d got there.

This was Big Wang’s longest absence yet, but his brothers, as they chatted while Middle Wang prepared breakfast as dawn broke on February 10th 1955, had no particular reason to think they’d never see him again.

This was the day when life was changed irrevocably not just for the Brothers Wang, but for all Big Chen Islanders.

In Episode Three: A Morning of Comings and Goings, we find out why on that morning, the Brothers Wang, previously inseparable apart from the odd trading trip, were separated, and how life was turned upside down for all Big Chen Islanders.