Our podcast The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories, from See Through News, Series 6, Teetering – how a Hawaiian beach bum held my career in the balance – finds Japan asking itself some awkward questions.

In Episode 5, gaijin (foreigners) suddenly pose a divisive question Japan has managed to avoid, until 1993.

Like all stories, it’s best to start at the beginning:

Episode 4 – My Favourite Japan Story

Next Episode 6 – How Chad Became Akebono (to receive notifications as soon as new episodes are released, subscribe to the See Through News YouTube channel or your preferred podcast platform).

Written, narrated and produced by SternWriter

Audio production by Rupert Kirkham

Podcast sting by Samuel Wain

Series sound composition by Simon Elms

If you enjoyed this series, why not try these ones…

- Series 1: The Story of Ganbaatar – the only qualified deep-sea navigator in Mongolia

- Series 2: Betrayed – A Tale of Christmas Spiritual Pollution

- Series 3: Life on the Edge – Taiwan, China, America and the Moment I Realised Mrs. Wang Was Mostly Guessing What Her Husband Said

- Series 4: The Quiet Revolutionary – the heroic role played in a plot to assassinate the King by someone you’ve all heard of

- Series 5: A Classical Chinese Dirty Joke, Told Thrice

The Truth Lies in Bedtime Stories is a See Through News production.

See Through News is a non-profit social media network with the Goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

For more visit seethroughnews.org

**

Transcript

Episode 5 – Can Gaijin Have Hinkaku?

Some stories are universal and timeless. Not this one.

Time and place are critical to our story, which took place in 1993, in Japan.

Even at the time, it felt like a pivotal point in Japan’s modern history. By 1993 we all knew that after decades of breakneck growth, Japan’s Bubble Economy was over.

Maybe you’ve not heard the phrase ‘Bubble Economy’. It’s an economists term, but back then had become widely used both in Japan and internationally to describe the country’s asset inflation. ‘Baburu keizai’ was part of everyday conversation, not just news bulletins.

Not everyone could explain the technicalities of a ‘sudden end to a period of inflated asset prices created by cheap money’. But we could all get the imagery – for Japan in 1993, things were changing instantaneously, irreversibly and for the worse.

The image of a bubble bursting, though powerful, is misleading. A bubble bursts in an instant. We can see its size, its location, any contents. The bursting of Japan’s Bubble Economy, took months, and the answers to those other questions are still revealing themselves decades later.

As Japan had grown to be the world’s second-biggest economy, and America was Number One, the Tokyo Bureau of ABC News was a great vantage point from which to observe this transition.

I was a Brit viewing Japan through Stars-&-Stripes-tinted goggles. It made for quite a show.

In TV technical terms, which I was gradually acquiring, the knobs for Contrast, Saturation and Hue were all turned up to 11.

After the fall of communism, the US-Japan relationship had become the most important bilateral relationship in the world. Many Americans feared that having won the Politics battle, they were about to lose the Economics war.

Foreign news rarely leads American news, but in the years before I joined, the ABC News Tokyo Bureau had regularly provided the top story on America’s most-watched evening news show.

Today it was Japanese money buying up an American icon like the Rockefeller Centre. Last week they were buying Pebble Beach Golf Course. Increasingly bitter trade disputes provided more and more flashpoints.

Japan, so long America’s Asian bulwark against Communism, now threatened to trample, Godzilla-like, all over the USA.

By 1993, these trade disputes were getting nasty. We did stories on how Washington was trying to force Tokyo to buy more American ski equipment, rice or cars. Few of our reports failed to include the phrase ‘invisible trade barrier’.

As an outsider with no dog in the fight, this was all fascinating. Importing skis and rice seemed a simple case of Japan’s protectionist foot-dragging, with some pretty funny excuses. ‘Japan has a different kind of snow’, they’d protest, with a straight face. We’d interview Japanese farmers, and Agriculture Ministry officials, who’d earnestly claim a Californian rice weevil could bring Japan to its knees overnight.

On other issues, the Americans were just as unreasonable. I particularly enjoyed our regular reports on delegations of irate Detroit car makers arriving in Tokyo to lobby about unfair trade barriers.

More interested in audiences at home, they’d grandstand about the pitiful levels of American cars exported to Japan. They’d contrast this with the intense competition they faced from Japanese car makers on American soil.

Compelling, on the face of it, and delivered with gusto and guile, but the best part of these press conferences was when a Japanese journalist would politely enquire when American car makers were planning to sell vehicles with the steering wheel on the correct side.

Other journalists might then point out the many adaptations Japanese car makers had designed for their export models. The more daring might specifically cite larger seats to accommodate fatter American buttocks. Oh, and putting the steering wheel on the correct side.

By 1993, things were turning particularly nasty. As the stakes, and tempers, rose, racism became more explicit, on both sides. A congressman from some midwestern farming state staged an eye-catching photo shoot. To drive home his enthusiasm for Americans buying American, he swung away at a Japanese tractor with a massive sledgehammer.

Good TV, maybe even good politics, but as the New York Times pointed out and many Japanese newspapers reprinted, economic nonsense. The Japanese tractor the Congressman was trashing, it turned out, had a higher percentage of American-made parts than the one with the American brand on it he was so keen to promote.

But this is my point. Like early Bond moves, 1993 was not a time for nuance, mutual understanding and sensitive cross-cultural exchange.

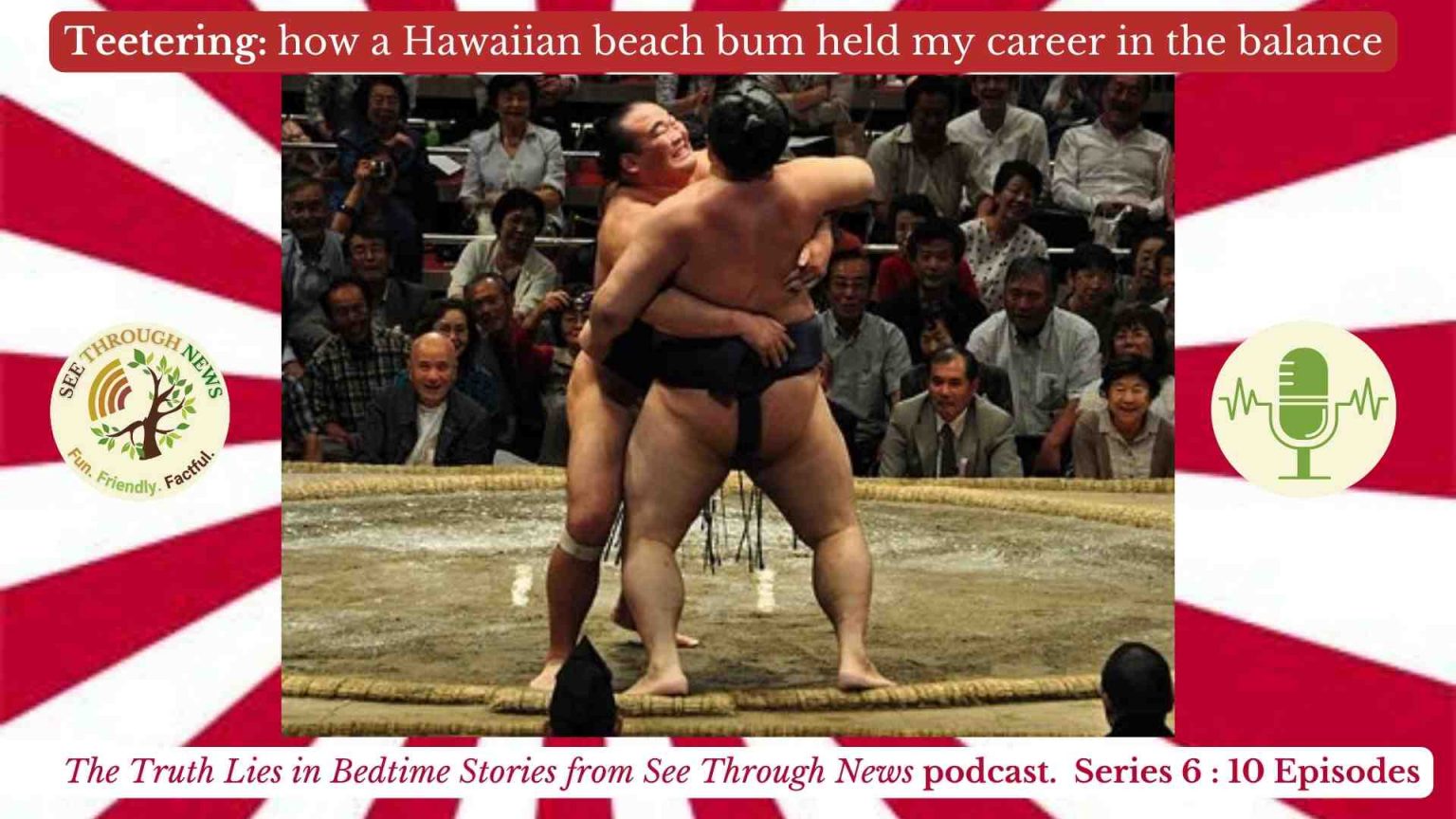

So what a time for American exports to be taking over the sumo market.

When I say Americans, specifically, it was Hawaiians.

The origins of this Pacific infiltration go back to the 60s.

A beefy Hawaiian from Maui called Jesse Kuhaulua abandoned his dream of joining the NFL. He moved to Japan to try his hand at becoming a professional sumo wrestler.

Standing 1.9 metres in his flip flops, weighing more than 200 kilos, Jesse had certain physical advantages. He was given the fighting name Takamiyama, which included the characters for ‘Tall’ and ‘Mountain’.

But Jesse was also a hard worker, a fast learner, and a keen student of Japanese culture, qualities admired in Japan. Jesse soon became a sumo fan favourite, and then Japan’s most popular resident foreigner.

Jesse was no novelty act. He rose to the rank of sekiwake – behind only ozeki – Champion – and yokozuna – Grand Champion. In the early 70s, he even won a tournament.

But that turned out to be the peak, for this Hawaiian man-mountain. After a record-breaking 20-year-long professional career, Jesse retired. Like many distinguished sumo wrestlers, he became an oyakata – a stablemaster, running his own training centre. He was the first foreigner to become an oyakata.

Jesse wondered if other Hawaiians might be ready to follow the path he’d trailblazed. The beefcake showcases that were Hawaiian beaches were a good place, he thought, to spot potential recruits.

Jesse knew better than anyone that bulk alone wasn’t enough. Candidates also had to be hungry, tough and determined. He was on the lookout for beach bums with attitude – a humble attitude. They had to be prepared to train hard, overcome homesickness, learn a new language, and adapt to Japanese culture.

Jesse’s Hawaiian beach patrols soon paid off. He found one gem, and others followed.

First was Saleva’a Fuauli Atisano’e, from Honolulu. His fighting name was Konishiki, a bit of a joke as it meant ‘little piece of brocade’.

At 287kg, Konishiki was the heaviest sumo wrestler ever. He’s the one foreign TV commentators dubbed The Meat Bomb, or The Dump Truck.

Then there was Fiamalu Penitani, born in American Samoa of a Tongan father and Samoan mother, before they moved to Oahu. Taller than Konishiki, a mere 50kg lighter, he took on the fighting name of Musashimaru.

Western commentators never came up with a nickname for him, though I always thought they’d missed a trick, as the first two characters of his fighting name meant ‘Ferocious Warehouse’.

By 1993, The Dump Truck and the Ferocious Warehouse were tearing up the rankings, reaching ozeki, the second-highest ranking, one short of the ultimate accolade of Grand Champion – yokozuna.

There’s something you should know about sumo at this point. Unlike boxing or professional wrestling, the top-ranked sumo wrestler does NOT automatically acquire yokozuna status. It’s not the same as being Number One. Mere winning doesn’t automatically confer this peculiarly Japanese kind of greatness.

There were unwritten conventions governing promotion to yokozuna, such as winning two consecutive tournaments as ozeki. But ultimately this honour is awarded at the discretion of the Japan Sumo Association. In particular, yokozuna promotion is decided by the nine members of its Yokozuna Deliberation Committee.

All very wishy-washy. All very vague. All very Japanese.

It’s hard to think of a more conservative, traditional, and resistant-to-change outfit than the Japan Sumo Association.

In the early 90s, there were two Japanese yokozuna, but they were often absent due to injury or illness. Lesser yokozuna tended to get injured or ill a lot, and not for the obvious reasons.

A yokozuna can’t be demoted. To preserve the dignity of the sport – and, one might add, to save the face of the Japan Sumo Association – dodgy yokozuna are expected to – metaphorically – fall on their swords the moment they lose their mojo. A temporary withdrawal is preferable to a losing record, but any hint that a yokozuna is over the hill, and they retire.

By 1993, sumo had never been more popular, but it was in urgent need of a worthy yokozuna.

The retirement of the legendary Chiyonofuji – The Wolf – in 1991, had left a massive void.

Two sons of a former ozeki showed great promise, and were rising fast up the ranks. But though sumo royalty, they were still teenagers.

The only candidates were foreign. Konishiki had been the first non-Japanese to break the ozeki barrier. His fellow-Hawaiian Musashimaru was well on his way.

A few months before, amid all the sledgehammer tractor smashing, and Yellow Peril paranoia about Japan overtaking, and taking over, America, something earth-shaking occurred.

Konishiki,The Dump Truck, won two consecutive tournaments as ozeki.

Usually, a promotion to Grand Champion would have been a formality, but this was just the kind of emergency situation that those wishy-washy, vague formalities were made so discretionary for.

The Yokozuna Deliberation Committee, came up with some invisible trade barriers.

They announced they wanted to make doubly sure that Konishiki was worthy of grand champion status. They darkly hinted that The Meat Bomb might not possess hinkaku. Hinkaku is a vague, untranslatable term meaning something akin to grace, elegance, or refinement.

A Japanese magazine obligingly published these remarks under the headline, “We Don’t Need a Foreign Yokozuna’. A rival publication claimed Konishiki was explicitly accusing the Yokozuna Deliberation Committee of racial discrimination.

The New York Times then directly quoted Konishiki saying, “If I were Japanese, I would be yokozuna already.”

The Japan Sumo Association demanded an apology. At a tearful press conference on live TV, Konishiki apologised and denied saying any such thing. He claimed a Hawaiian apprentice had impersonated him on the telephone.

All this was, as you might imagine, front page news on both sides of the Pacific. Sumo, of all things, was gifting journalists a spectacular TV metaphor for the tension in the world’s most important bilateral relationship.

Like all foreign and Japanese media, the Tokyo Bureau of ABC News, was all over it. And not even the Japanese staff at ABC News Tokyo were as all over it as their greenhorn British Ass Prod.

Just when we thought it couldn’t get any better. At the height of all the bubble-bursting, tractor-smashing and racism-denying firestorms, another Hawaiian was promoted to ozeki.

And then started winning sumo tournaments.

In Episode 6, How Chad Became Akebono, we learn how this latest foreign import came from a Hawaiian beach to become the tower of muscle that threatened to smash Japan’s most Invisible Trade Barrier.