Floods have provided great cautionary tales throughout human history – what can they now teach us about speeding up carbon drawdown?

Flooding: no joke

A middling English city, a small English city and a small English town, go into a local government conference to discuss flood defence.

The middling English city says ‘I’ve developed a sudden fear of floods’.

‘That’s funny’, say the small English city and the small English town in unison, ‘so have we!’.

‘Why is that funny?’, asks the middling English city.

‘It’s not funny at all’, say the other two. ‘We thought this was some kind of joke’.

They then compare notes, discover they’re all facing the same problem, but are addressing it in different ways.

None of which is particularly funny, but to be fair, we are talking about global heating and possible civilisational collapse.

The Global Heating Problem

The problem faced by these three English communities is their localised versions of our human-induced climate crisis.

From a storytelling point of view, the Greenhouse Effect’s big problem is that its consequences are disastrous, but understanding its causes requires a sophisticated grasp of Science.

Even more problematically, science can explain why floods are getting worse because of human intervention, but they can still look like pre-Industrial ‘natural’ disasters.

This science communication challenge has long been exploited by those feeding our fossil fuel addiction. For bad actors, cautious boffin precision is simple to translate as ‘they don’t know what they’re talking about’.

Humans are good at Science, but slow to accept our discoveries. It takes time and effort for science to percolate ‘from ivory towers to the street‘. We need to act fast, but plenty of bad actors still impede the march of science.

We’ve suspected it since the 70s, proved it since the 90s, and the evidence grows more overwhelming, and terrifying, by the day. Our species caused global heating, and only our species can reverse it. Well, not exactly reverse it, we’ve left it too late for that. More accurately, only humans have the capacity to mitigate global heating’s worst effects, which get worse with every day’s delay.

Unlike past man-made disasters, the Greenhouse Effect is planetary. Its cumulative impact, considered from an individual human life span, appears slow. The time lag between cause and effect, and the geographically dispersed, uneven and locally unpredictable nature of these impacts, mean the Science behind our climate crisis is unintuitive. It contradicts the daily experience we value as ‘common sense’.

This is the same common sense that tells us our planet is flat, the Sun passes above us, and disappears underground at night. The evidence of your own eyes can’t always be trusted.

Science, combined with good storytelling, can change ‘common sense’, over time. But we don’t have much time, and we’re fighting our other superpower.

Selfish v Scientific superpowers

The rocky ball we live on is around 4.5 Bn years old.

We reckon life on Earth started around 3.7 Bn years ago.

The dinosaurs, who we mock as a metaphor for failure, lasted 165 million years – though as some of them are still around, let’s call it 225 million years and counting.

Homo sapiens has been around for the last 300,000 years or so, arguably 160,000. In either case, a blink of a dinosaur’s eye.

When we started farming, around 12,000 years ago, humans started having a minor impact on the thin smear of living stuff that covers the rocky ball we cling to (though at the time, we didn’t realise it was a ball).

Considering we only started digging up and burning fossil fuels in earnest around 150 years ago, not long after we worked out our planet was spherical, not flat, it’s not surprising we’re taking our time to adapt to the consequences, even thought the science has been obvious for some time.

The tribal tools humans have evolved to favour our particular community’s survival tend to come at a cost to other communities. So far, this zero-sum approach has worked OK overall, from a species perspective. The stronger prevail, take over the resources previously used by weaker rivals, and multiply. The weaker appear in our museums as excavated skulls in glass cases.

This process goes by different names, from ‘survival of the fittest’ to ‘God’s will’, but let’s not get bogged down by existing labels. It’s been characterised as our ‘Selfish Gene’, so how about calling it our ‘Selfish Superpower’.

Unfortunately, our Selfish Superpower turns out to be worse than useless for the particular problem of global heating. Blaming others, negotiating, fighting, tricksterism, have all served us well so far. That’s why we’re so good at them. When faced with previous problems, like competition for resources, feeding ourselves, or making our lives more comfortable, Oour Selfish Superpower has served us well. Why not this time?

This time, the problem is different, and our Selfish Superpower is making it worse, not better.

Fortunately, homo sapiens has evolved other superpowers, like tool-making, abstract thinking and projection. Let’s call this our Scientific Superpower.

The bad news is our Scientific Superpower came up with the internal combustion engine that triggered this existential crisis.

That other bad news is that even though our best future as a species depends on our Scientific Superpower prevailing over our Selfish Superpower, so far it’s losing.

If you’re waiting for the good news, welcome to the problem.

Or rather, our nest of interconnected problems. To get our arms round this massive existential challenge, this article examines one localised aspect, flood defences. We’ll look at flood control from the perspective of a middling English city, a small English city, and a small English town.

First let’s clarify why this is a different kind of problem. Why, when it comes to our climate crisis, are our Scientific and Selfish superpowers not collaborating, but locked in mortal combat?

The climate crisis response Russian doll

The Greenhouse Effect acts on all human communities on the planet, but unevenly. This problem has broadly been identified as ‘climate justice’.

- The impact is worse on poor countries than rich countries

- Within countries, it’s worse for poor people than rich people

- Among rich people, it’s worse for the 99.9% than for the top .01%

This is a particularly bad time to permit this tiny elite to be calling all the shots. They form the Three-Headed Beasts of Government, Business and Media, the See Through News allegory for our human condition. ‘Connected below the neck by Power, and below the waist by Money‘, the Three-Headed Beasts may snap and bicker at each other, but they still control everything, including our stories.

Especially our stories. Three-Headed Beasts are Selfish superpower supervillains.

The super-rich are insulated from the impact of global heating, the Three-Headed Bests prefer to prolong business for as long as possible. From their perspective, any behavioural change risks a loss of Power or Money.

Unfortunately, it’s the top 0.1% who own most of our media, and therefore control the stories we tell each other. Appearances can be deceiving. Many of them appear to embrace out Scientific Superpower, because their digital fortunes were built on new technology. Tech forms the basis of their infantile ‘solutions’ to climate change, from abandoning this ball of rock for another one, or inventing magic machines to make the problem disappear.

Anything, rather than changing the behaviours on which they’ve built their billions.

If the tech elite’s Scientific superpowers come into direct conflict with their Selfish Superpowers, it’s not even a close contest.

Plenty has been written about this problem, peaking annually at Davos, attended by billionaires flying in on private jets to sort out climate change.

This article focuses on three very particular local instances, to tease out lessons for the rest of us as we all grapple with our personal, community and species-wide superpower face-offs.

Climate crisis is so overwhelmingly huge, our first challenge is identifying the nature of the problem.

The climate crisis is actually a Russian doll of problems, each nested inside another. Many different faces are painted on many of these matryoshka dolls, but to keep things simple, let’s narrow it down to these five:

- The doll on the outside is Human Civilisation (we could say ‘The Planet’, but See Through News doesn’t find it helpful to conflate our fate with that of our rock ball).

- Next biggest is Communication.

- Inside that is Climate-related behavioural change.

- Then there’s adapting our infrastructure to rising temperatures.

- In the middle is the particular issue of flooding.

Let’s examine this innermost doll, flooding.

We’ll look at one national example, and the three very local examples mentioned at the start of this article, and see if we can find any lessons that might help us inform bigger problems globally.

The Flood Problem

Humans have tended to live and build close to rivers and coasts. The benefits of living next to water are too many and obvious to list, but there’s always been a trade-off.

Rivers and coasts flood. The bigger the flood, the greater the harm to the inhabitants. Small floods damage property. Big floods kill people.

To mitigate these risks, we build flood defences. Throughout history, rulers and engineers have always faced the same complex equation. They need to trade off the short-term cost of building stronger flood defences against the long-term cost of repairing the damage.

Also in the mix is the potential for any mid-term benefit their flood defence-related actions might accrue during their lifetimes. Such calculations demand a complex mix of Selfish and Scientific superpowers, making them hard to separate.

Fundamentally, this trade-off depends on accurate calculations of risk – how often can we expect how bad a flood?

Or to paraphrase Dirty Harry, as he asks a criminal if he reckons there was a bullet remaining in the revolver he was pointing at his head, do we feel lucky, punk?

Floods and human civilisation

Entire civilisations have been built on this Selfish/Scientific superpower balance. Engineering, political and statistical decisions have dictated flood defence throughout history. Consider:

- Even today, 95% of Egyptians live by the Nile, and water drives its politics.

- China’s rivers still define its civilisation, the fate of its dynasties depending on how well the central government protects its citizens living by them.

- The history, economy, culture and agriculture of the Indonesian island of Bali is based on its water temple system, a melding of science, religion and governance.

- 90%, and rising, of Australians live by the coast, leaving more than 90% of their country virtually uninhabited.

Empires have risen and fallen based on the incumbent ruler’s expertise – or luck – in judging how much capital to invest in flood defence, and managing the consequences of flooding.

When a Pharaoh or Emperor gets it wrong, or happens to be incumbent when the heavens open, they find floodwaters wash away more than citizens, infrastructure, homes, crops and farm animals. Floods can also destroy the demi-god status they require in order to rule.

Religion and patriotism have their limits, and natural disasters always test those limits. Earthquakes have always been a crap shoot. Even with our advances in seismology and engineering, quakes remain an uncontrollable and unpredictable risk, with limited options for minimising their impact.

Because their causes were, until recently, so mysterious, seismic events, like eclipses, could easily be chalked up to divine intervention. Either way, they’re beyond human control, and our mitigations are limited.

Flood, fire and famine are less easily explained away, especially now the advance of science is replacing such explanations as ‘Fate’, ‘Kismet’, and ‘Heavenly Will’ with ‘tidal barriers’, ‘forestry management policy’ and ‘geopolitical proxy warfare’.

Of these three, flood defences are the easiest for ordinary people to grasp. Maybe that’s why we’ve tended to hold our rulers particularly accountable for floods. We may not give ‘the authorities’ much credit when flood defences work, but we blame them big time when they fail.

Our trust in elected representatives these days is considerably less than our historic faith in divine rulers. For really bad floods, the limits to our faith can be measured by flood gauges. A millimetre can separate success from disaster.

For residents whose lives are upended, this impact is immediate. For rulers, their problems start once the flood waters recede, and blame is allocated.

The fate of individual rulers, dynasties and entire civilisations have been determined by their capacity to control river and sea waters. This has never been truer, now our fossil fuel addiction means really bad floods are suddenly more frequent.

Floods are where our Selfish and Scientific superpowers collide. It’s a numbers game, a gamble. The odds are changing rapidly in a direction that doesn’t favour rulers who neglect Science. But not rapidly enough.

When a massive deluge or tidal surge might wash away your power, rulers should make Science their ally. A timely technological breakthrough, effectively implemented without bankrupting themselves or their people, could save their skins.

So might investing in older proven technologies.

Or, as we’ll shortly discover, abandoning old solutions altogether once you realise the odds are no longer in your favour.

Our Science Superpower has steadily improved over the few thousand years since we abandoned hunting, gathering and nomadism in favour of farming and permanent homes. Our understanding of flood physics, the accuracy of our statistical analysis, and our engineering ingenuity have all grown along with our population, and the cities we’ve moved into.

So, at this point in our self-induced climate crisis, what’s our Science Superpower telling us when it comes to floods?

Flood Solutions

Flooding has no permanent solution, because it’s a constantly evolving problem.

The main, and obvious, factor, is how much rain we can expect to fall, and how quickly.

Average rainfall may be predictable over decades, centuries, even millennia. The problem is, it only takes one exceptional inundation, one extra centimetre, to push water over your defences, and you may as well not have bothered.

Actually, it’s worse than that. The longer the interval since any community’s last flood, the greater the risk for any ruler. The more memories fade, the more complacent we become. We build where we shouldn’t, we object to being taxed to pay for stronger defences, or even to maintain the current ones. All absolutely fine, until it isn’t.

Flood control technology is both very simple, and very complex.

Its complexity can be seen in our museums. Different cultures, at different times, have produced an amazing array of engineering solutions. Not just infrastructure like dams, dikes, groynes and polders, but technology. The internal combustion engine, the machine that sparked out current climate crisis, was invented to pump water from where we didn’t want it, to where we wanted it.

Its simplicity lies in the unchanging laws of hydrological physics: water always finds its own level, and can only flow at a certain speed.

We can build bigger and stronger dikes, invent more powerful pumps, store more water behind bigger dams, create more capacious reservoirs, build more ingenious tidal flood barriers, but all the while there are more of us, living more densely in bigger cities with more expensive infrastructure. And as our atmosphere heats up, more rain is falling in shorter periods.

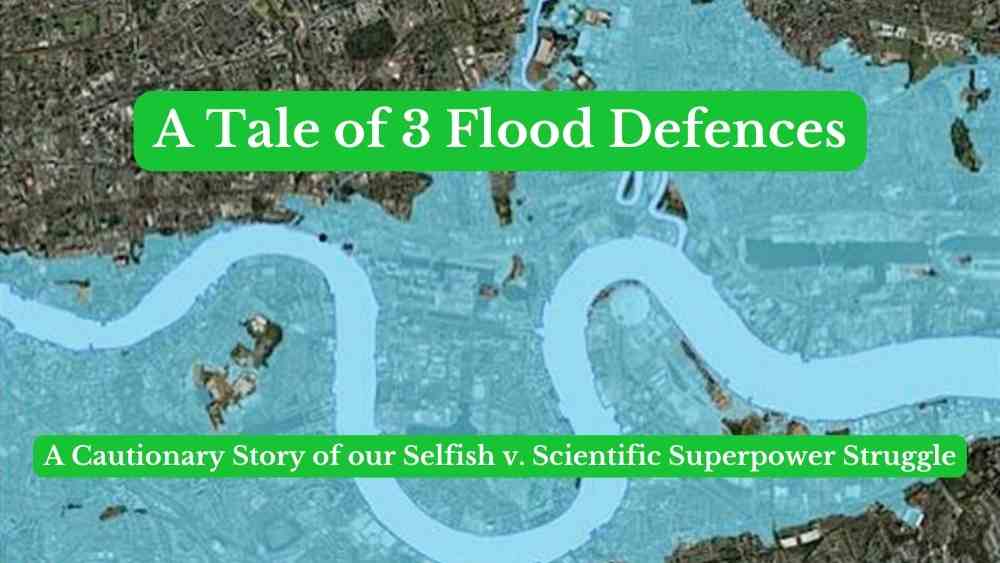

Take this map, created by the UK’s Environment Agency to explain the critical importance of London’s Thames Barrier.

Remove its flood defences, and London looks very different – the Thames turns from a snaking artery into a wide delta. All those famous sightseeing landmarks, and thousands of homes, now submerged.

Powerful cartography: effective storytelling.

Stopping floods with storytelling

This is where we leave the realm of statistical analysis, dike engineering and enter the world of storytelling, or in modern terms, ‘comms’, ‘PR’ or ‘controlling the narrative’.

In pre-industrial times, regal/imperial comms took the form of religion. In post-industrial times, leaders have favoured associating themselves with patriotism. When things go wrong, wrapping yourself in a flag has similar downsides to claiming the mandate of heaven – it offers little protection in times of stress, whether that’s man-made war, or nature-induced disasters.

Modern systems of governance have mostly abandoned claims to godly powers. Rulers of advanced economies either claim their legitimacy through the ballot box (‘democracies’) or via ideological or might-is-right nationalism (‘autocracies’).

These power mechanisms present different challenges, each with its pros and cons. Autocrats get to plan longer term than election cycles, but the stakes of failure are much higher. Decades of unconditional power v. hanging from a lamppost. Swings and roundabouts.

What democracies and autocracies have in common, however, is their legitimacy depends on good storytelling. To gain and keep the support of the masses, 21st century leaders need to clearly tell us what they’re doing, and convince us it’s good for us, via media old and new.

What a time then, for the odds determining flood control policy to change so suddenly. Our 150 years of collective fossil fuel addiction is changing our atmosphere and climate at a rate no past ruler has ever had to contend with.

Flood control is a particularly sensitive bellwether of how well we’re doing. The link between fossil fuel combustion and heavier rainfall is beyond question, and beyond politics. Atmospheric physics takes its course, we have to deal with the consequences.

The odds governing flood control have never changed faster in human history. Until recently, rich countries’ standard for an acceptable level of flood risk was to build infrastructure capable of withstanding up to a ‘1-in-10,000-year event’, on the grounds this was sufficiently unlikely a contingency for us to justify spending more money to make our infrastructure even safer.

But global heating is now turning such events into ‘1-in-1,000-year events’, ‘1-in-100-year events’, even ‘1-in-10-year events’.

Under this shifting tide, how well are our systems of governance shored up?

Flooding and global heating

Global heating means the rivers are breaking their banks, and the sea our coastal defences, increasingly often.

Flood defences that have protected us for centuries are now failing unacceptably often. Evacuation isn’t an option. Ignoring the problem hasn’t worked. The only solution is better flood defence.

We’ve written elsewhere about how the world’s flood experts dealt with climate change. The Netherlands, with ⅓ of their country below sea level, have long been the world leaders in flood control and alleviation.

Bitter experience has taught the Dutch to favour Science over Selfish. A quarter of a century ago, seeing the projections, trusting the science, and terrified by the models, The Netherlands made a radical shift in flood control policy.

The Dutch recognised they’d reached the physical and financial limits of continuing to build bigger, stronger dikes. Facing reality, having done the sums, and after poring over the projections, they abandoned centuries of resistance. They switched to a new policy they branded ‘Room for the River‘.

Room for the River, as the name bluntly suggests, means accepting there’s going to be more flood water, and creating more space for it. Practically, it involves the kind of earthworks familiar to children playing on beaches. The main one is moving riverside dikes further apart, to provide more room for flood water and reduce the speed of the flow.

Essentially, the world’s flooding experts gave up trying to defy nature. After centuries of fighting water, they acknowledged there was no point in fighting physics, and decided to make a huge behavioural change.

This was a national-scale storytelling challenge. Generations of Dutch have been told they had to build bigger, better, stronger dikes, dams, pumps and polders. For them, Science had made this ‘common knowledge’. As self-evident as the earth being round, or revolving around the sun, and not vice versa.

But all of a sudden, that was Old Science, to be replaced by New Science.

When Dutch leaders introduced Room for the River, they must have felt like the Catholic church admitting Galileo Galilei was right after all. In 1633, the Catholic Inquisition forced the astronomer, under threat of torture, to recant his heretical ‘belief’, based on scientific observation, that the Sun, and not Earth, was at the centre of our solar system.

Galileo died in 1642. 180 years later, in 1822, the church admitted Galileo was right. In 1992, after a papal committee had studied the issue for 13 years, the Pope formally rehabilitated Galileo’s reputation.

The Dutch government knew it couldn’t wait 359 years to publicly change its colours. It rapidly devised a major publicity campaign to sell its Room for the River story to their people. They taught it in schools, they hired topic creative talents to produce TV ads, featuring trusted celebrities explaining the physics lying fully clothed in a bath with the tap running.

They invested a huge amount of time, effort, publicity, education and advertising in explaining their new policy. By and large, The Netherlands has escaped the worst floods seen elsewhere in Europe since. Never say never, but so far so good.

Room for the Rivers is an outstanding national-level example of best practice in science communication, to change public perceptions, to enable a new public policy. Have the rest of us learned anything from the world’s best flood-dodgers?

Let’s return to our three English communities, and find out. Our case studies involve successively lower levels of government, all beneath the national level exemplified by Room for the River.

Britain is a rich country, but relatively typical in the sense that while flooding regularly causes misery and economic damage and is getting more common, people don’t often die. For Britain, flooding doesn’t present the immediate existential crisis it does for The Netherlands, or poorer low-lying countries like Bangladesh, the Maldives, or the Pacific Islands.

We’ll look at three examples, in diminishing scale:

- a city of 200,000

- a city of 43,000

- a town of 3,000

All have a historic association with water and flooding. All are trying to do something about it, with differing degrees of success.

Case Study 1: Portsmouth’s ‘Southsea Coastal Scheme’ Project

Portsmouth, population 200,000, lies on England’s south coast, facing the Isle of Wight.

Portsmouth is the historic home of the British Navy, and has long been a key port for commerce and passengers. It’s actually an island, Portsea, connected to the mainland via bridges and motorways. As a densely-populated island, Portsmouth is very floodable.

The city’s sea defences have historically been combined with military defences, but these days Portsmouth’s existential threat comes not from Armadas, but from rising sea levels caused by the Greenhouse Effect.

The Southsea Coastal Scheme is Britain’s biggest local-government-lead flood control scheme. Portsmouth can’t compete with the kind of resources available to a country like The Netherlands, but as a large city it has more options than most local governments.

The scheme’s budget is a hefty £160M, and is designed to protect 10,000 homes. The project claims it will protect the city for the next 100 years. In truth this depends on how quickly we stop burning fossil fuels, and hence how quickly sea levels rise, but maybe the local authority can be forgiven for not highlighting this in their publicity. Changing peoples’ minds is hard enough, without alarming them too.

For the purposes of this article, our point is that this scheme has loads and loads of publicity. You can’t ignore the piles of concrete tetrapods, diggers and trucks along the sea front, so everyone in Portsmouth is aware of the works, which operate 24/7. Building a stronger sea wall will be occupying the entire sea front for years to come.

Noticeboards explaining these works are everywhere. They apologise for the disruption and temporarily spoiling the view, but also explain the project’s critical purpose, and its urgency.

As a result, most people in Portsmouth accept the disruption. They can explain to visitors why it’s necessary, important and urgent. Stakeholders were consulted, some are being compensated, life goes on.

You can always find grumblers if you look for them, but you’ll also see plenty of locals taking their kids to watch the diggers, and helping them read the placards explaining the project’s goals and importance.

All things considered, full marks on the critical issues. Rated on humanity’s twin superpowers, and the outcome, Portsmouth’s Southsea Coastal Scheme reaches Dutch standards:

- SCIENCE: Well conceived

- SELFISH: Well communicated

- OUTCOME: Well implemented with goodwill all round

(Details of this and similar projects, and the local response, can be found via See Through News’s Facebook groups, in this case:

- local community Facebook group, See Through Portsmouth

- county level group See Through Hampshire

- regional-level group, See Through South East)

Case Study 2: Salisbury’s ‘River Park’ Project

Unusually for an English cathedral city, the city of Salisbury, in the south-west county of Wiltshire, has a very precise date of birth. It grew around its famous cathedral, on which construction started in 1220. As it was built on a flood plain where five rivers merge, flooding was an issue from the off.

Over centuries of draining and hydrological works, including an elaborate system of ‘water meadows’, Salisbury developed robust flood defences to protect the city’s growing population, currently 43,000.

In 2018 Salisbury appeared in global headlines when bungling Kremlin goons failed to assassinate Sergei Skripal with novichok nerve agent, which weeks later killed a local woman.

Around the same time, a quarter of a century after The Netherlands introduced Room for the River, Salisbury too came to realise changing rainfall patterns meant control was no longer feasible, and decided to opt for increased containment.

The ‘River Park’ scheme is Salisbury’s local version of ‘Room for the River’. Essentially, the city is relocating the riverside dikes further back, retreating to create more room to capture floodwater. This will protect more houses from rising risk of flood. The budget is £27 million, mostly central government flood defence funding.

These funds are administered by The Environment Agency, Britain’s national-level body, which is also coordinating the works, scheduled to finish December 2023.

You may have noticed the word ‘flood’ doesn’t appear in the project’s title.

For better or worse, this project is being packaged as a city beautification project, rather than highlighting its core purpose. This is a storytelling choice.

In this sense, the project ‘Masterplan’ is actually a masterpiece of misdirection. Expertly, opportunistically, cunningly, the designers have used the opportunity of shifting large amounts of earth in the city centre to create new parkland. They’re connecting existing green spaces into a ‘green lung running through the heart of the city’.

The Masterplan acknowledges temporary disruption due to the works, and the sacrifice of a few parking spaces in the central car park, but explains this will all be more than offset by all the new green areas, new playgrounds, separate cycle and pedestrian paths, eco-friendly mini-habitats etc. etc.

All rather brilliant, but a glance at the project’s woeful website tells you not much of this budget has been allocated to Communication. Formal public ‘consultation’ boxes were ticked, but when the bulldozers moved in, Salisbury’s population was almost entirely unaware of the project.

Efforts by local activists, alarmed at the lack of information, to help communicate the project’s importance, were ignored. Not because of budgetary reasons – they were offered free of charge as a community service – but simply because no one could say who was in charge, and no one in charge wanted to make a decision on what they clearly saw as a minor matter.

As predicted by the local See Through News community news Facebook Group See Through Salisbury, the works are going down very badly with the locals.

As soon as the groundwork began, local social media was full of outrage about necessary short-term downsides like trees being chopped down, otters being displaced, and playgrounds demolished. Residents were entirely ignorant of the many long-term benefits, even the huge long-term reduction in their insurance policy premiums reduced flood risk would bring.

Selling River Park as a beautification story made selling it as a money-saving story even harder, not that the authorities told either story with much conviction. This negative publicity was amplified by Salisbury’s ‘local’ newspaper (actually owned by a New York hedge fund). Clickbait stories recycling online outrage are easier, and more lucrative, than ethical journalism or public service.

Salisbury’s 43,000 residents may eventually be proud of the results of the River Park project, but unlike the locals of Portsmouth, you can’t find many who can even explain the real flood-prevention purpose of the River Park Scheme, let alone feel any civic pride in it.

Salisbury’s River Park was a great opportunity to communicate critical climate science via positive local examples, but the authorities blew it. Maybe because there were so many different partners involved (the Environment Agency, the contractors, the county council, the city council), the task of explaining it fell between the cracks.

Maybe focusing on the cosmetic results, and avoiding the key flood-prevention purpose of the scheme, could have worked. Maybe they reckoned any mention of ‘climate change’ risks alienating ordinary people, yet to be convinced it existed.

More likely, they lacked the expertise, or even the understanding of the challenge, to handle the storytelling element. To engineers, everything looks like an engineering problem. They favour Science Superpower.

For whatever reason, any chance of using the statutory consultation process as anything more than a box-ticking exercise, was lost. Done creatively, with good storytelling, this could have done the narrative groundwork to get the locals onside, earn their forbearance and buy-in.

But no, despite its £27M budget, this flagship project was spoiled, for what Portsmouth sailors would call a ‘ha’p’orth of tar’.

Salisbury provides a good example of the risk of not engaging with our Selfish Superpower, and relying on our Science Superpower alone. In summary:

- SCIENCE: Well conceived

- SELFISH: Poorly communicated

- OUTCOME: Well implemented, with avoidable ill-will

(More details on the project, and the local response, can be found here:

- local community Facebook Group, See Through Salisbury

- county-level group See Through Wilsthire

- regional-level group See Through South West)

Case Study 3: Appleby Flood Risk Management Scheme

Our final case study is the smallest in budget, population and scope. Maybe that’s why it may not even happen.

Appleby is a small market town in a rural area of the north western county of Cumbria, bisected by the River Eden. Every summer, its profile is raised by the Appleby Horse Fair. Travellers and gipsies from around the UK and beyond gather in the shallows below the bridge at the town centre, to wash, display and trade horseflesh.

For the rest of the year, Appleby is a quiet, rural community, its local business dominated by four main employers, who occupy the town centre by the bridge. Like everywhere in Cumbria, famous for its Lake District, Appleby has suffered several major floods in recent years. Centuries-old flood defences are now being overwhelmed by global-heating-induced rainfall intensity.

In December 2020, Appleby’s local council was asked to consult on an Environment Agency proposal to address this increased flood risk. The Appleby Flood Risk Management Scheme, as reported in the local press, claimed it would protect 60 properties from flooding, and take 6 months. The budget eventually settled at £1.5 million.

The local council ticked all the consultation boxes, and raised no objection to its approval. The bulldozers were all set to move in until local residents started inspecting the small print.

It emerged that the Scheme would actually only protect 28 properties, cost £6m, and take 20 months. It would also remove town centre parking spaces. In a rural area like Appleby, ill served by public transport, everyone has to drive. For local businesses in Appleby, there’s no footfall without parking.

Once they started investigating the procedures by which the project had been uncritically waved through, local residents uncovered a litany of dodgy dealing, procedural failures, face-saving tactics and outright deception.

Mayors and councillors have resigned, replaced by new councillors seeking to reverse the approval, and start from square one, and do it properly this time.

In the meantime, rain will continue to fall, the river will continue to flood, and Appleby’s residents will be more vulnerable to property damage.

Whether through misplaced allegiance or incompetence, Appleby’s flood control project has been disastrous, even on its own terms. Had local governance worked as it should, the flaws on the Environment Agency proposal would have been revealed much earlier. The supervising authorities could have intervened, but didn’t. The regional newspaper could have performed the kind of monitoring role it has in the past, when it was independently and locally owned, but didn’t.

Since being hoovered up by corporate agglomerator Newsquest, the Cumberland News & Star is little more than an advertising platform for its ultimate owner, New York hedge fund New Media Investment Group.

The News & Star’s reporting on the project has been limited to an uncritical puff piece, parroting information from a press release, quite possibly released by an important advertiser. The decline of independent local newspapers, with 70-90% of remaining local titles now being owned by corporate agglomerators, is a big problem. The ‘news deserts’ they’ve created negatively impact local democracy, holding power to account, and climate storytelling.

Even without this external pressure, and upstream institutional checks and balances, a strong, independent-minded local council could have prevented this fiasco. Specifically, disaster could have been averted if the people implementing the project had paid more than lip service to the consultation, education, and storytelling element.

In short, the Appleby project fails on all counts:

- SCIENCE: Ill conceived

- SELFISH: Poorly communicated

- OUTCOME: Failure, with avoidable ill-will.

(For more details on the project, and the local response, visit the See Through News local-level Facebook Groups:

- See Through Penrith, county-level community group

- See Through Cumbria

- regional-level group, See Through North West)

Lessons

What do these case studies, along with The Netherland’s Room for the River example, tell us about the role of storytelling in effective climate action?

From a communications point of view, the problem with global heating is that its causes and effects are so widely separated in time and space. Those who profit from business as usual exploit this. It’s what makes effective climate action so hard, and climate denial so easy.

Ordinary people aren’t used to understanding or making connections between their own behaviour, and the need to change.

- Mitigating the worst impacts of global heating requires massive, rapid, behavioural change.

- This can only happen via Government Regulation, not individual decisions.

- Government Regulation change is only possible with public pressure and support.

- We need to rapidly improve our system of government to favour Science of Selfishness

The lessons of this article, related to dealing with the consequences of global heating, are even more urgently applicable to dealing with its causes.

There’s a huge competition for our eyeballs in the real world, and online. An inundation, in fact. Most of this flood of information, data and advertising contributes to the problem of global heating:

- directly, because it burns fossil fuels – not just obvious things like flying and driving, but using The Internet itself

- indirectly, by persuading us to buy more stuff we don’t need that requires the burning of fossil fuels – for all their hi-tech dazzle, our Silicon Valley Overlords are fundamentally advertising companies – and by delivering greenwash and other forms of ineffective climate action that waste time, create complacency and divert resources.

The same conduits that channel this flood of carbon-increasing information can be used to deliver carbon-reducing stories. They’re just conduits.

As we hope this article makes clear, carbon-reducing stories are every bit as important as any technological breakthrough, political announcement or billionaire philanthropist PR stunt.

Effective storytelling is a critical, but overlooked, component of our collective flood defences against the worst impacts of global heating.

To prevail, they need to be cracking stories, cunningly told, starting with a broad range of topics that interest and engage ordinary people, each facilitating a journey towards the same destination, of measurably reducing carbon.

Hence the See Through News Goal of Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active.

The case studies we’ve looked at come from elective democracies, but the same power dynamics operate in autocracies, and the same mistakes when it comes to flood control and climate change mitigation.

However our rulers rule, we should be alert to narratives that favour Selfishness over Science, and tell better stories.