One environmental activist’s sliding door moment, involving the back of a Chinese dictionary 40 years ago

Four decades after what turned out to be a life-changing decision, Robert Stern traces how a grammatical curiosity involving horses lead him to found See Through.

Life-changing Decisions

We all like to think we’re in control of our destinies. We’re adept at reinventing our own life stories to confirm this illusion.

The truth is that most forks in the road aren’t obvious at the time, and we need hindsight to discern the paths they lead us to. Dig deeper into anyone’s confident account of their ‘life-changing’ moment, and you usually find it wasn’t actually quite so obvious at the time.

We dress up the past because it’s in our nature. Humans are pattern-seeking mammals, and we really don’t like chaos. Homo sapiens’ superpower, abstract thought, enables us to arrange, shoehorn, pigeonhole and categorise the chaos of reality into meaningful structures.

No surprise, then, that we apply the same process to our favourite subjects – ourselves. Even less surprising is our ability to retrospectively construct narratives that cast us in the best light: wise, far-sighted, prescient, smart – not oblivious, ignorant or obtuse.

If our lives are streams of consciousness, we punctuate them with meaningful moments in order to make them make sense. We identify ‘life-changing moments’, and play around with the timeline to make ourselves look better. Unintended consequences are re-labelled as ‘foresight’. Accidents are re-branded as ‘decisions’. Coincidences are credited to fate, divine intervention, or some other greater power directing us.

This is the story of one such ‘life-changing moment’, one which I can retrospectively claim lead me to do what I do now – help run the international pro bono network of experts motivated by measurably reducing carbon, See Through.

Unlike most such moments, this one did involve a clear fork in the road. I knew at the time that I was taking a binary opt-in/opt-out, Yes or No, red pill or blue pill decision. I just had no idea of its long term consequences. Also, the thing that tipped me into changing course involved horses and bolts of cloth.

Forty years on, this is as accurate, true, and transparent an account that I can muster describing the choice that I took, why I took it, and where, forty years on, it has lead me.

So brace yourselves for a true story involving China, grammar, and measurable carbon reduction.

Universities in the 80s

The 1980s were not a bad time to be a British teenager filling out a university entrance application form.

The UK may have been sliding into imperial decline, but when it came to higher education, 1960s meritocratic aspirations could still prevail over ‘market forces’.

In the ’80s, students could still afford to study what they wanted. A few years ago, watching my daughters and their friends agonise over filling in their university application forms, I recounted my experience of this important rite of passage, marking the first step from childhood dependence to adult independence. Their eye-rolling reaction was part regular Dad response, but also exasperation at being told about ancient history that had nothing to do with their situation.

For them, the prospect of a lifetime repaying student loans, and the reality of universities that marketed themselves like businesses, meant choosing where and what to study was a far more practical matter.

How could they repay the ‘loans’ they take out for uni fees and living expenses, if they did what I did, and followed their whim? They’re filling out their applications in a world where universities market themselves with glossy brochures that look more like retirement home prospectuses, the awarding of degrees is a transaction correlated to an institution’s prestige (the less prestigious the uni, the higher grades they dish out), and a student’s ‘investment in their future’ is literal, not figurative.

Ivory towers have been replaced by production lines. Banks and law firms are no longer fine with hiring Art History or German Studies graduates. Neither they, nor their employees, view banking or lawyering as a skill easily acquired on the job by intelligent, curious, motivated young minds, as it was ‘in my day’.

It seemed almost cruel to reminisce about when I filled in my UCCA (Universities Central Council on Admissions) form. Then, Britain was still anchored to European academic values, yet to drift across the Atlantic attracted by American ones. For me and my friends, filling in our UCCAs was more a careless act of whim than the carefully-considered career choice it has become.

Of course, a few of my classmates knew what they wanted to be – a doctor, an engineer, a banker – and chose their courses accordingly. But for the rest of us, uni was a free hit. University curricula were yet to be driven by market demand. Employers really did see a university education as mind-training, not a vocational qualification.

When I filled in my application form, future employment wasn’t a factor. I was told employers weren’t too bothered about the particular topic you chose to study, and were more interested in the fact that you were studying at all. University ‘taught you how to think’, no matter what you were thinking about, my teachers and parents told me.

Quaint, and annoying, for teenagers today to hear this. But, in 1982, broadly true.

Some things haven’t changed

Let’s not go overboard. When I filled in my UCCA form in 1982, university education was still a privilege enjoyed only by a minority. Barely 10% of young people went to uni, compared to 50% today.

Also, just because the government paid your study fees and gave grants for living expenses didn’t mean the murky connections of nepotism, Old Boy networks or the British Class System were suspended once you applied for jobs.

And not all courses were viewed equally by everyone. Then, as now, certain courses attracted more students with particular bents: Maths for scientists, Law for lawyers, Engineering for engineers, Politics & Philosophy for liberal arts types, Geography for farmers, French, German and Spanish for teachers or translators.

Some courses were considered as obscure, and hence eccentric to study, back then as they are today: Egyptology, Sanskrit, Theology.

Or Chinese.

In 1982, when I hastily filled in my UCCA form at the last minute, looking over the shoulders of my similarly-blasé schoolmates for inspiration, Chinese was the last thing I was thinking of studying.

Edinburgh sounded nice, so it put it at the top of my list. I’d never been there, but it seemed to induce approving nods from teachers. They also seemed to find my line that I wanted to ‘study abroad’ amusing. As for the course, I scribbled in ‘Politics and Philosophy’, on the grounds that I’d not studied either yet, and it seemed a popular choice.

My focus, and that of my classmates, was on what’s now called my ‘gap’ year. When you’re 18 (I was still 17 when I left school), a year is a long time. I wanted to make the most of the year between me and university.

I posted my UCCA form, binned my revision notes, and started looking for a temporary job to pay for my round-the-world air ticket.

I had the grades required by Edinburgh University’s Politics and Philosophy course, and soon had a confirmed place for when I returned home. The quicker I could earn, the sooner I could start to experience the world as an independent adult, free from uniforms, exams, and formal study.

If you’re curious about the job I found, and what I did on my gap year, these are also key elements of the story. Each of which could be given starring role of ‘life-changing moment’, if I so chose.

These and other pieces of the puzzle, all these little links in the chain, or ingredients in the mix, are part of the infinitely complex vortex of contingencies, what-ifs and nudges that make up our life. They’ll appear later, as bit-part extras, rather than headline Sliding Door titles.

This is my story, so I’m doing the casting.

Matriculation 1983

When I showed up at Edinburgh in the autumn of 1983, I’d barely given my university education a thought.

When the student volunteers handed over my student ID card, they explained I’d need to sign up for another course. It turned out my joke about ‘studying abroad’ had a ring of truth, as Scotland had a different education system from England.

Unlike English universities, where you only studied whatever you’d been accepted for from day one, Scottish universities required you to do three courses for your first year. I was happy to discover this. I’d only chosen Politics and Philosophy because I wanted to try something new and different. Why not add something else?

My chosen courses accounted for two-thirds of my quota, so now I had to pick a third. I could select any course in the Arts Faculty that fitted my schedule.

Thus, a couple days later, I was among the throng of hungover teenagers traipsing around a large hall, browsing this academic buffet for my additional course. Through the bodies, I made out the dishes on offer: Ancient History, Celtic, Fine Art, Sociology.

At the far end of the hall was a relatively deserted table, advertising the Chinese Department. I later learned it was the only one in Scotland, which makes this whole story even more coincidental, if you like to think of it in those terms.

I made a beeline for it.

The reason was simple – I thought I’d have a head start. Three months of my gap year had been spent in Thailand. This was hardly unusual – even in the early 80s, Thailand was part of the standard gap year banana pancake trail.

But instead of hanging out with other foreigners on the beaches, my three months had been spent living with Thai families belonging to doctors my neurologist father had either studied with, or taught.

This wasn’t the only unusual privilege my remarkable father given me. Before I’d even boarded the plane, Dad’s out-of-the-box maverick mind had provided another out-of-the-ordinary leg-up.

At dinner, I’d been entertaining my family with stories of the part-time job I’d landed, as temporary secretarial assistant at the Farrier’s Registration Council of Great Britain, surely the quietest backwater of the British civil service, and just as Dickensian as it sounded. A tiny walk-up office in a warren behind King’s Cross. Dark wooden panels. Bewhiskered Registrar. View of a brick wall.

Maybe when the Registry was established, Great Britain had many more horses to be shod, but by 1982, if I really stretched it out, I could register my daily quota of farriers within about 10 minutes of the three hours for which I was being paid, every morning, Monday to Friday.

Aware that experiencing a boring job was part of the point of a gap year, and reminding myself this was paying for my place ticket, I stuck out the tedium.

Dad, however, came up with an idea of how I could spend my farrier-registration-free time more usefully.

One lunch break, Dad walked a block from University College Hospital to the School for Oriental and African Studies, and enquired if the languages they taught there included Thai.

Dad had a knack for this kind of thing. By the end of his lunch break, he’d not only located Britain’s only Professor of Thai, but returned to the hospital bearing a plastic bag and a broad grin.

That evening, he presented me with the plastic bag. It contained a photocopied stack of A4 paper, and two cassette tapes. The former were the teaching materials the Professor of Thai had written for his first-year students, the latter copies of the language lab resources used to teach conversational Thai.

I took them to work, and started getting stuck in. Copying out the exotic twirls, curls and twists of its ‘abugida’ script, with my Walkman headphones as I mumbled the Thai equivalent of ‘ecoutez et repetez’ under my breath, certainly beat staring at a brick wall for two hours and fifty minutes a day.

Thus, the paucity of British farriers and the generosity of the civil service’s temp budget, meant that when I arrived in Bangkok, I could just about read and write the 44 consonants and 28 vowels of the Thai alphabet. I could decipher them even more painfully slowly, and hold a basic conversation, so long as I was asked exactly the same questions in exactly the same sequence as the language lesson tapes.

By the time I left, I’d acquired more than the usual please-and-thankyou basics my friends on the beaches had picked up. I was far from fluent, but could haggle at markets, entertain children, and hold simple conversations, even if they diverged from the cassette tapes.

Hence, a few months later, the beeline for the Chinese Department table at Freshers Week.

I had a smattering of Thai, which had five tones. Chinese, they told me, only had four.

I already knew that A-Level Spanish meant I could busk a basic conversation in Italian.

Thai, Chinese – how different, I reckoned, could they be?

That’s why I chose Chinese, to bulk out my major degree courses.

Studying Chinese in 1983

I rapidly discovered my smattering of Thai provided me with a head start of about an inch, but before describing my first encounter with Chinese, I should put it in context by doing the same for my first-year Politics and Philosophy classes.

The contrast was immediately obvious, and got bigger as the weeks passed.

The Politics and Philosophy lectures were attended by hundreds of students in vast, cold, echoing halls. They were delivered in monotones by barely visible distant lecturers who appeared to have delivered exactly the same script a year previously, and looked like they’d rather be somewhere else. In some cases, anywhere else.

My fellow students didn’t add much appeal. So many students attended these first-year courses, I found myself sitting next to different people every time. None showed much interest in socialising with me.

This was understandable. Most hung out with friends from school; so far as I knew, I was the only person from my school to attend Edinburgh that year.

They also seemed much younger, and most were. Scottish students graduated from school at 17, and most went directly to university with no gap year.

I was also becoming dimly aware of the underlying antipathy many Scottish students felt for the minority of English students. Cringing at the ‘Hooray Henry’ crowd of mainly public school English students, as they emulated the antics of Brideshead Revisited fops, or Bullingdon Club louts, I saw their point, but this made it no easier to bridge Scottish students’ shyness or suspicion.

The smaller seminars were even less stimulating. Scottish students arrived at uni having studied a wider range of subjects for longer than their English classmates, but in less depth, particularly in your uni course speciality. I’d not done Politics or Philosophy for A-Level, but was already familiar with quite a lot of the content of the first-term lectures, so had to wait for my classmates to catch up.

The seminars should have been livelier than the big hall lectures, but turned out to be even more painful. Some were taught by inexperienced PhD students who’d rattle on, neither permitting nor seeking interruption. Worse were the ones taught by better teachers, who’d punctuate their monologues with increasingly desperate pleas for someone to ask, or even answer, a question. I was often the only one to break the silence, my dozen Scottish classmates preferring to keep their heads down and their mouths shut.

The Chinese classes, by contrast, were a hoot.

They were held in the basement of the tiny Chinese department, in a small, cosy room, that held around twenty students sitting in rows, like a school classroom.

The windows behind us revealed a stone wall topped by railings, and the feet of passing pedestrians, but our attention was always focused on one of the department’s four lecturers, each eccentric in their own way, as they taught us Chinese from scratch.

Two were particularly brilliant, old-school professors, who loved teaching and were fantastic at it. They ignored, even scorned, the academic authorities who were starting to lean on them to publish more papers, apply for more grants, and bump up their research citations.

Bill Dolby and John Scott saw themselves as conduits for an academic tradition stretching back millennia. Their missions wasn’t to rack up citations in academic journals, but to inspire the 20 blank slates before them, and open their minds to unimagined possibilities. Half the class had were doing Chinese as their major. I was in the other half, who’d picked Chinese for their non-essential course. Either way, we were a bunch of oddballs, and none of us knew a thing about Chinese.

Standing at the whiteboard, like conjurers revealing their secrets, our lecturers demystified this bizarre writing system. Stroke by stroke, character by character, they revealed the logic behind these pictograms, teaching us how to decode them, hinting at the depth and richness of the poetry, literature, culture and philosophy we’d be able to access if we persevered.

Dolby and Scott were brilliant storytellers, leavening the rote repetition required to learn to write these characters with background nuggets explaining how China converted a system of pictograms scratched into turtle shells and ox femurs thousands of years ago into a modern writing system. They made the connections between the language and grammar, the writing system, and the culture that created one to transcribe the other.

- First, the raw materials – the repertoire of brush strokes that make up the characters.

- Then how these strokes formed the basic components.

- Then how these components could be divided into the ‘radicals’ (denoting meaning) and ‘phonetics’ (denoting pronunciation) that make up each character.

- Then, how the combination of Chinese grammar and characters meant that each character could perform multiple different roles depending on its context: noun, verb, adjective, adverb.

Every lesson was a seamless tapestry of art class, history lessons, philosophy lecture and linguistics, when all they were doing was teaching a bunch of British teenagers what Chinese kids learn in primary school.

While we struggled with the basics known to Chinese six-year-olds, our teachers would hint at the sunlit uplands that awaited us once we’d mastered them. Deploying their own lifelong fascination for Chinese language and culture, they motivated us by expertly dangling delicious, distant fruit. Keep at it, and you’ll be able to read Tang dynasty poems in the original. Persevere with your tones and your grammar, and you’ll be able to converse with a billion people. Keep practising your characters, and you’ll be able to read Chinese newspapers.

As we were all starting from scratch, we all learned new things at the same time. After lessons, we’d retreat to bars and bedrooms, common rooms and cafes to do our homework, practise our tones, invent surreal mnemonics to remember how to write characters, test each other with flash cards. We pretended not to notice when other students, eavesdropping on us, shook their heads in amazement.

As you may have gathered, Chinese knocked Politics and Philosophy into a cocked hat.

As the weeks went by, our progress accelerated. After taking a week to learn our first character, we’d learn one in a day, then five a day. After crawling through Lesson One, we managed Lesson Two a bit quicker, Lesson Three quicker still.

The path ahead, through a long way from the destination painted in gold and silver by our teachers, was at least becoming discernible. As the dream of fluency in Chinese and the ability to decode its script became more desirable, it also seemed more feasible.

Chatting to classmates who’d chosen Chinese as their major course, I soon heard about an even more immediate prize.

I’d not really thought about it, but it made sense. If you studied French, you spent a year in France. If you studied Russian, you had a year in the Soviet Union.

If you studied Chinese, it turned out, the government actually paid you to live in China for a year.

China in 1983

It almost certainly wasn’t Napoleon who described China as a ‘sleeping giant’ who shouldn’t be woken, but when he was alive, this quote, commonly attributed to him, was already an accurate reflection of China’s sad decline.

Napoleon was around during the few centuries during which an ascendent Europe carved up the world, coinciding with the ‘Century of humiliation’ during China was demoted from Empire to colony.

When China wasn’t sleeping, it was being torn apart by foreigners. Once the Chinese Communist Party kicked out the foreigners in 1949 and put up a Bamboo Curtain, we’d occasionally glimpse China doing a fine job of tearing itself apart.

Either way, in 1983 there wasn’t much reason to study Chinese at university. China may have had the world’s biggest population, but it was only just emerging from decades of self-harm. The Cultural Revolution ended with Mao’s death in 1976, but Beijing was still dealing with the aftermath. If the giant wasn’t asleep, it was still pretty dozy.

As Deng Xiaoping asserted control, China’s door had opened a sliver. Some diplomats, a few journalists, a handful of enterprising business people, occasional groups of wealthy, curious tourists glimpsing China through tour bus curtains, slipped through, but China in 1983 was not much more accessible than North Korea is today.

This obscurity was reflected at British universities, where Chinese probably had as many professors teaching it as Sanscrit.

Now this door had opened to me, an 18-year-old Politics & Philosophy major dabbling in Chinese 101.

I’d discovered that although Scotland’s higher education system was slightly broader than England’s – that was why I’d got the chance to study Chinese as my third course – it was still a long way from the US or European system, where you could taste a wide buffet of courses in your faculty before nominating your major.

I made some enquiries at the Faculty office into whether it was possible to switch to Chinese. Yeeeees…, came the answer, we might be able to swing it for you if you really really want to.

But did I want to?

I’ve laid out all the tedium, isolation and boredom of my Politics and Philosophy classes, and contrasted them with the energy, thrill and stimulation of the Chinese department, but this makes the choice look obvious.

There’s a reason why, decades later, I defined the See Through Goal as ‘Speeding Up Carbon Drawdown by Helping the Inactive Become Active’. The second bit is the hard bit.

Humans are neophobes – fearing the new has been a reliable evolutionary trait. When the default is X, you need a very good push, pull, or both, to switch to Y. Opting out requires more momentum if the default is opting in.

Inertia usually prevails. It’s hard to get people accustomed to inaction to take action – even when confronted with overwhelming scientific evidence, in the case of climate change.

I wouldn’t have put it that way had you asked me at the end of my first uni term at the end of 1983, but this was one of my early adult experiences of this phenomenon.

Over the Christmas holidays, I sought advice from my parents. They wisely declined to tell me what to do, or even advise me one way or the other. They gently pointed out I was now the only person who could make these kind of choices for myself. Dad, as neutrally as he could, asked me what I most enjoyed, and advised me to pursue it. If writing a letter to the University would help, he’d be happy to do so, but such decisions weren’t up to him any more.

My friends couldn’t really help me either. They’d enjoy my pub tales of making up mnemonics for how to write characters. I’d scribble 群 , qún: crowd, or group on a napkin, and tell them it was easy to remember, because it was just a picture of Desperate Dan without a hat leaning over a counter to order a triple-decker bull pizza on a stick. A fun party trick, but Chinese still sounded a bit weird to them.

So, there I was, teetering, at a fork in the road. Should I ask to switch courses?

I still couldn’t quite take the leap into the unknown. All I needed to do so was a tiny nudge, but I’d not yet encountered it.

It was then, that, doing some holiday homework, fed up after copying out Desperate Dan ordering pizza for the hundredth time, I idly flicked through the appendices at the back of my newly-acquired Chinese/English dictionary.

There were useful lists of things. Some were familiar, like the Chinese versions of the Periodic Table, weights and measures, or the official translations of all the nations in the UN, and their currencies. Others were bafflingly esoteric, like the lists of ‘The Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches’ and ‘the Twenty-Four Solar Terms’ , which included ‘The Waking of Insects’, ‘Grain in Ear’, and ‘White Dew’.

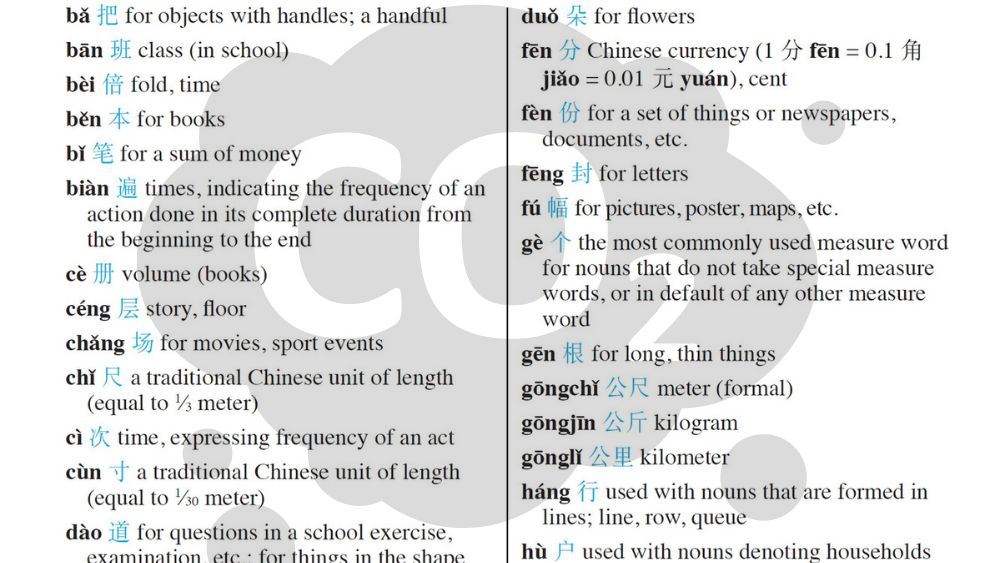

Among them was a dense table titled ‘Common Chinese Numerical Adjuncts’.

It was barely legible, but as I happened to have just learned what a ‘numerical adjunct’ was, and thought there was only one of them, I paid it closer attention.

Always read the small print

We’d been introduced to the concept of the ‘numerical adjunct’ in Lesson 1 or 2, so I had a rough idea of what the appendix headed ‘Numerical Adjuncts’ was about.

The concept wasn’t hard to grasp, especially when you hear the other terms for the same thing, like ‘counter words’, ‘categorisers’, or, directly translated from the Chinese term, ‘measure words’. Even better, English has numerical adjuncts too, we were just never told that’s what they were called.

Numerical adjuncts, we’d been taught in an Edinburgh basement, are the units we use to enumerate certain things: five loaves of bread, two slices of toast, 100 head of cattle, 3 prides of lion etc.

Chinese, however, is particularly persnickety about them. You must use one whenever you count anything. If you use a number, you must insert a numerical adjunct before the noun you’re counting.

We were taught the basic catch-all one 个, ge. You could count anything using ge, but if you didn’t insert it between a number and the noun in a test – no marks, nul points, wrong, incorrect.

This was the extent of my command of numerical adjuncts when I came across this appendix, but as I looked down the long table of entries, I gradually realised I’d barely scraped the surface.

You’ll never be wrong to use ge, in the sense that it would be wrong in English to say ‘a loaf of cattle’ or ‘a pride of toast’, but this poorly-printed table revealed to me that only using ge all the time would make you appear ignorant, ill-educated, stupid or foreign. Not wrong as in saying ‘three units of toast’ or ‘five units of bread’, but clunky and betraying a paucity of vocabulary, as in ‘bigly’.

On the other hand, as I scanned down the columns listing the dozens and dozens of other common numerical adjuncts, I experienced a cultural shift. A whole new world revealed itself, an entirely different, but just as logical, way of viewing the world, just through a different set of lenses.

- 张 zhāng: measure word used with flat objects like paper, cards, tickets, desks and tables.

I’d never thought of a ticket and a desk being the same ‘kind of thing’, but yes, they do share the same characteristic of being flat, when you think about it.

- 条 (tiáo): measure word used for long, thin things like rivers, snakes, fish, trousers, roads etc..

I could rattle off a hundred ways of classifying rivers, or fish, before I’d thought of them both being long and thin, but once you’ve seen the connection, you can’t unsee it.

- 口 (kǒu): measure word used for things with mouths like people, cannons, wells etc.

I get it!

Now I’m starting to see how this works, and how something as simple as counting objects provides a profound insight into an ancient culture.

But I still hadn’t decided to switch my major to Chinese.

Horses, bolts of cloth etc.

Then I came across the one that did it, the nudge I needed.

The single item in the list of numerical adjuncts that tipped me over the edge, the impetus that drove me from inertia to motion, the trigger, the catalyst, that made me take a different path from the one I was taking. Ready?…

- 匹 (pī): measure word used for things like horses, bolts of cloth, etc.

To be even more specific, it was that last word that tipped me over the edge.

How could you possibly list two reference points as disparate as ‘a horse’ and ‘a bolt of cloth’, and then casually add ‘etcetera’?

What language, what people, what culture could specify a species of odd-toed ungulate, a way of packaging textiles and, not be bothered to add one more example to triangulate what they had in common, instead airily saying ‘etcetera’?

You know – horses, bolts of cloth, that sort of thing! Why not gibbons, ribbons, that type of malarkey? Or dumplings, casement releases, stuff like that?

I had to find out. I wrote a letter to the head of the Arts Faculty, requesting a switch to Chinese.

Why Chinese?

That decision set me down a different set of rail tracks. Along with innumerable other switches, detours, halts, reversals and branches, it ended up with me setting up See Through, to speed up carbon drawdown by helping the inactive become active.

Life’s far too complex and contingent to prove I couldn’t possibly have got to the same destination via other means. But I can draw a line, however circuitous, wobbly and occasionally indistinct, from my decision to study Chinese to deciding to give up paid work to measurably reduce carbon in 2021. Some landmarks along the way:

- 1984: Making Japanese friends while studying in China

- 1987: Getting a first job with a Japanese multinational

- 1991: Quitting to try to become an environmental consultant in Tokyo

- 1995: Falling into TV news, and reporting business news from Hong Kong, Shanghai

- 1997: Seeing China’s environment collapse as its economy boomed at CNN Beijing

- 1998: Hearing one of my Japanese friends explain how carbon trading worked in practice

- 2000: Making environment-related documentaries for Japanese public television

- 2003: Consulting for China’s first F1 Grand Prix, as it embraced car culture

- 2007: Teaching workshops for Chinese documentary filmmakers on social issues

- 2013: Crowdfunding to make doc on woodsman living model sustainable life

- 2016: Docs for charities in Central American narco-states degrading their environment

- 2021: Found See Through News

- 2022: Found See Through Carbon

A zig-zag journey, sure, but if I can’t connect the dots in my life, who else can?

Throughout, people have asked me ‘Why did you decide to study Chinese back in 1984?’.

Over the years, I’ve given a variety of answers, mostly ones that modestly, but flatteringly, reflect on my remarkable prescience in spotting the Rise of China when everyone else thought it was a basket case.

Too modest to make it obvious, I’ve nonetheless permitted people to conclude that I was way ahead of my time, a genius prognosticator, a Nostrodamus whose opinions on all matters should be taken seriously, as endorsed by my wisdom in choosing the path less travelled in 1984.

But, as you now know, none of this was actually true.

Had you asked me on the way to the postbox, bearing my letter to the Edinburgh University Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, why I’d chosen Chinese, my stock answer at the time was ‘I decided to switch as soon as I discovered the government was going to pay for me to live for a year in China’.

This isn’t what I’d written in the letter, but nor was it entirely untrue. It was the self-conscious, show-off, answer of a slightly subversive teenager going for a nerdy-cool look.

The opportunity to experience China as a student in 1984 was a perfectly good reason to switch, among many other I could have mentioned. But it wasn’t the actual one that tipped the balance.

Until now, it never seemed the right time to explain the true reason – the word ‘etcetera’, stumbled across at the back of a dictionary.

Chinese, connections, and carbon

Does this all still seem a bit convoluted? Does this mini-memoir read as a contrived way to shoehorn a grammar gag into a late-career choice many see as a mid-life crisis?

I can understand why, so let me try to spell out why I think this is all connected.

For a start, let’s take the Chinese word for connections, familiar to anyone who’s done business with China – 关系, guānxi.

Like its English translation, guānxi carries a range of connotations from ‘networking’ and ‘human relationships’ to ‘back-scratching’ and ‘nepotism’.

I learned all this from my decision to study Chinese, which may have encouraged me to value guānxi, and practise it. There’s nothing uniquely Chinese about human relationships or networking, but what I experienced working in China, and indeed the Japanese corporate culture my China decision lead me to, taught me to value interpersonal trust as well as contractual terms and conditions.

Lasting relationships can be made in the karaoke bar as well as the boardroom. All human relationships are ultimately based on trust.

We are all the sum of our human relationships. In my case, I’ve been fortunate enough to have lived, studied, worked and travelled around the world, meeting like-minded people and experts in a wide range of fields, many of whom have become lifelong friends.

Well before social media made such things easier, I was ‘good at staying in touch’. I was the one who organised reunions, dropped by, caught up, with no particular ulterior motive. I’m still in regular contact with friends from primary school, secondary school, university, work colleagues both when I was employed, and self-employed.

These connections have been critical in getting the See Through ball rolling. I’ve repeatedly found myself only a phone call away from world experts in everything from China, to AI, branding, editing, sound engineering, coding, IT infrastructure, cybersecurity, web design and all the other innumerable cogs required to build a global network on zero budget.

Three years on, what my AI chums call ‘the network effect’ is kicking in. New volunteers and partners are being introduced by people to whom I’ve been introduced. I didn’t know See Through’s IT project manager until someone I met through a See Through project introduced him. He’s now managing a full-stack coder who was introduced by a different friend, who recently met him in a different context.

None of us is being paid, because See Through has no money. They’re all motivated by our common goal of measurably reducing carbon.

Each new contributor had their own multifarious, complex, tangled paths. Each brings their own sliding doors memoir, their own version of stumbling across a table of numerical adjuncts among dictionary appendices. Whatever the route, we’ve all arrived at the same conclusion.

Whether they’re from Britain, India, Nigeria, Japan, Uganda, Mexico, Hungary, Australia, The Philippines, we’ve all concluded that the most important thing we as a species must do is to urgently reduce carbon.

In See Through, they’ve seen an innovative way of doing this, where money is not a requirement, but an obstacle, and not having a bank account is an imprimatur of integrity, and proves our approach to be the polar opposite of ‘worthless’.

Would any of this have happened had I not switched to Chinese in 1984?

None of us can ever know.

But I hope this apparently meandering memoir has demonstrated the importance and power of See Through’s other key feature, in addition to measurably reducing carbon without money.

Storytelling.