Trees are canaries in our climate coal mine – what will happen to our forests & woodland in 50 years if we do nothing now?

Trees take decades to mature, but our climate is changing fast and unpredictably. This presents forestry, timber and woodland management with an urgent, immediate challenge – what can we do now to avoid predictable future catastrophe?

First, grasp the nettle

No one likes to confront inconvenient truths.

Politicians, toddlers and pub bores share an armoury of rhetorical tools to avoid such ‘unpleasantness’.

Here’s a fabricated analysis of made-up data pulled out of the air to lend authority to that evidence-free assertion:

| Tool | Politician | Toddler | Pub Bore |

| Denial | ‘There’s not a shred of evidence that I’ve ever supported…’ | ‘It wasn’t me’ | ‘Come here and say that’ |

| Distraction | ‘The opposition have spent years telling you…’ | ‘She did it’ | ‘Tell you something, though, what about…’ |

| Deflection | ‘What’s important to focus on is…’ | ‘How about me?’ | ‘What I was going to say was…’ |

| Diffidence | ‘We have many priorities, and need to do the right thing…’ | ‘I don’t care’ | ‘Yeah well, whatever, it is what it is…’ |

The See Through News Superhero and Supervillain Drawing Competition teaches schoolchildren how to spot and address these tricks, and distinguish Superhero rational debate from Supervillain rhetorical bluster.

Better learn young. Adults deploy these tricks all the time, particularly when finding reasons not to confront the reality of human-induced climate change.

By grasping the nettle, you avoid getting stung. But what about the Triffid-like oncoming waves of nettles that may follow? Pain will be involved, it’s just a matter of how much we can avoid by taking action now.

When is comes to climate change, we’ve left it too late to avoid any kind of pain.

Still, fronting up to scientific evidence now can spare us avoid a whole lot of avoidable future grief.

So what nettle should we grasp today?

Trees and climate change

Trees often come up when we talk about climate change for various reasons, such as:

Visibility

Trees are a land-based life form. As terrestrial mammals, we think and care about trees a lot more than we do about marine algae. The Amazon is more on our minds than Atlantic plankton.

Biodiversity

We’ve seen nature documentaries on a single rainforest tree supporting dozens of as-yet-unnamed endemic species of moss, beetle, fungus and wasp, not to mention the more charismatic macrofauna, the birds and mammals we can name. All depend on trees for food or habitat.

Sequestration

Politicians, engineers and investors get very excited about Direct Air Carbon Capture (DACC) technology These are big machines that might one day be able to suck carbon from the air and return it to the ground. They’re appealing because they don’t require us to do anything now to stop putting more carbon up there, and might earn some people a lot of money. DACC may work one day, but we don’t have time. In the meantime, nature has created fantastically efficient proven tech to do the same thing. Trees.

Offsetting

Most carbon offsetting programmes depend on paying someone to either a) get someone else, usually distant brown people, to plant trees, or b) at the very least to promise not to cut down any existing trees. Over 30 years, offsetting has created a multi-billion-dollar industry, a lot of paperwork, and repeated exposure of its ineffectiveness/fraudulence. Carbon emissions are still rising.

British trees and climate change

Britain provides a particularly interesting lens through which to examine humanity’s current tree problem, and possible future solutions and mitigations.

From a global perspective, Britain is a particularly interesting canary in the coal mine to observe for lessons elsewhere.

Bald Britain

With only 13% tree cover, the UK is among Europe’s least forested countries. The EU average is 38%, the global average 31%. The fewer trees you have, the bigger the negative impact of losing the ones you still have, and the greater the positive impact of planting more.

Island Britain

The British Isles, as islands, have a particular control over biosecurity. More than continental countries where borders are political rather than stretches of water, Britain can control far more than most countries which species are introduced from elsewhere, and how infested they are with pests and disease. As a developed economy with sophisticated border controls, Britain is unusually placed to monitor the introduction of new species, should it choose to. In the past, it’s chosen to allow the import of pathogen-riddled saplings of ash, a native British species, from the Netherlands because they were marginally cheaper, so’s there room for improvement. Note that biosecurity isn’t the same as xenophobia – the Romans introduced the sweet chestnut to Britain 2,000 years ago. Like a 4th-generation Scottish pizza restauranteur called Hamish Mancini, Castanea sativa is welcomed to the UK with open arms as an honorary native, and included on approved lists of species to plant in British forests. Japanese knotweed, Reynoutria japonica, introduced in 1850 by Victorian botanists as an ornamental plant, not so much.

Expert Britain

Britain may be slipping down various international league tables after a long run of success, but one area in which the UK can still claim, in the phrase so beloved by its diplomats, to ‘punch above its weight’, is academic research. The UK may not have many trees, but it has a lot of tree experts.

So, who should we listen to?

Next, listen to experts

Heads removed from the sand, fingers extracted from our ears, our next task is to understand the facts.

Not the ‘facts’ you choose to search for, or which a social media algorithm trained on the prejudices of you and people it thinks are like you presents you with, in order to confirm your existing prejudices. We’re talking about research published in scientific journals by experts, not ‘doing your own research’ down online rabbit-holes.

‘Facts’ are what AI-generated listicles show you to persuade you to read the ads next to them. Facts are what we’re talking about. The kind agreed on by experts who spend all day, and entire careers, studying the subject. The kind extracted from the text of research papers, not tabloid headlines, or IPCC ‘summaries’ edited by civil servants and politicians that dilute facts presented to them by their own scientists to avoid panicking their voters/citizens.

We’re all free to ignore scientific research. Conspiracy theorists like to think of themselves as Galileo, shunned by the Church for saying the Earth revolves around the Sun, or the child in the crowd who laughs at the naked Emperor while everyone else applauds his imaginary New Clothes. Cassandra, cursed to know the future but not be believed, is another popular role model for the discerning know-it-all narcissist.

What makes conspiracy theorists conspiracy theorists, is the fact that Galileo was advancing scientific observation and mathematics over religious dogma, the Emperor ruled by fear, and Cassandra is a myth designed to highlight how rubbish humans are at listening to experts.

So now we know we’re grasping the tree nettle, in particular British trees, and what kind of experts we’re talking about, we’re ready to move on.

What are British tree experts saying about trees and climate change?

What 46 British Tree Experts Reckon

The UK’s Forestry Commission recently paid for the country’s top tree experts to produce a ‘horizon scan’ on the state of British trees.

Written by a leading tree researcher at the Cambridge University, based on the contributions of 46 leading British tree experts, the Oxford University Press’s journal Forestry published their report A horizon scan of issues affecting UK forest management within 50 years

If you’re not 100% sure what a ‘horizon scan’ is, the lead author, Dr. Eleanor Tew, who’s also Head of Forest Planning at the UK government body the Forestry Commission, starts by explaining this standard academic methodology.

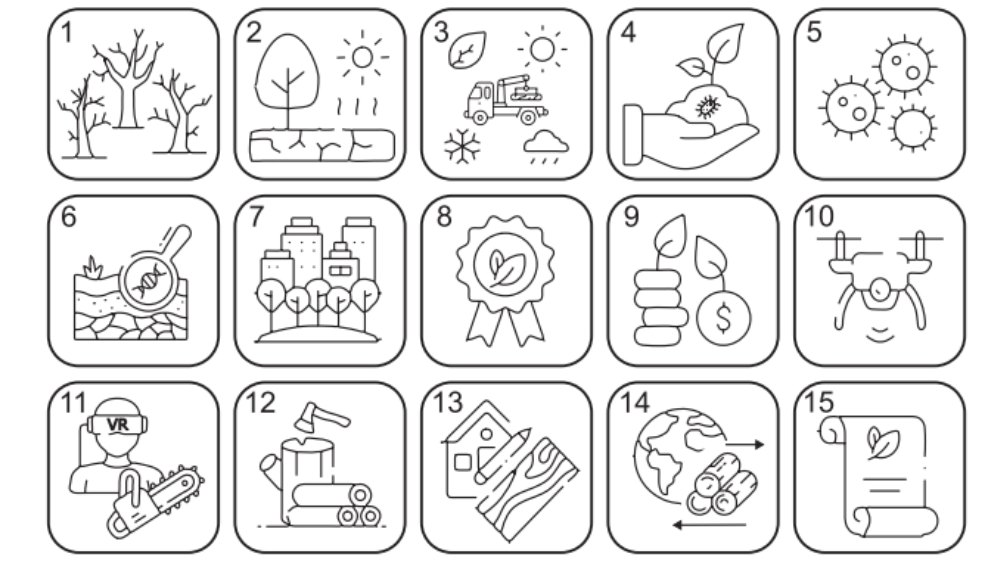

Dr. Tew and a core group of experts compiled a longlist of 180 issues. They circulated it among 46 expert contributors, asking them to rank them, with comments. They then listed the top 15. Pop quiz:

- Q1:What did the experts vote as the Number One issue facing British forests in the next 50 years?

- Q2: How many of their top 15 can you predict?

Dr. Tew helpfully made a graphic representation of their top 15 shortlisted issues. How many of them can you guess at?

The Top Problem is…

Before addressing their Top Fifteen biggest challenges for British forests – and more importantly, what we can do about it – you might be curious about how their report was covered in the media.

We mention this because media coverage may be the biggest problem of all. It didn’t appear on the 180 issue shortlist, nor did it make the experts top 15. Should it have?

After all, at least Cassandra was heard, before she was ignored. If everyone ignores the messengers, the message doesn’t matter.

The Guardian, Britain’s most consistently expert-listening and nettle-grasping publication, published one article about the report under the headline:

UK forests face catastrophic ecosystem collapse within 50 years, study says

Alarming’ new research warns of risk to British woodlands from disease, extreme weather and wildfires, unless ‘call to action’ is heeded now

The Daily Mail, Britain’s leading mid-market news source, didn’t cover the report at all. There’s nothing about it all on their website. If you search for ‘Forestry Commissions, the Daily Mail online provides a link to an PA Media press agency report titled

Experts predict `catastrophic ecosystem collapse´ of UK forests within 50 years

In other words, their editors read that PA headline, and didn’t consider it worth getting a Daily Mail staff journalist to write about.

The Sun, Britain’s best-selling tabloid, didn’t mention the report either. Search their website for ‘Forestry Commission’, and it does return the following headlines, all on The Sun’s favourite theme of xenophobia:

- BUG LIFE Urgent warning to Brits as toxic caterpillars invade UK causing rashes and breathing problems

- CREEPY CRAWLY Urgent health warning as Brits told to avoid ‘serious problem’ garden pest – know the signs to look out for

- BUG INVASION HELL Urgent warning to Brits as horror plague of toxic insects stings its way across Britain

All these breathless Sun warnings of foreign invasion were based on Forestry Commission guidance to woodland and forest owners on managing the oak processionary moth (Thaumetopoea processionea). The Sun’s ‘toxic caterpillar’ is an oak-loving moth first identified by Linnaeus in 1758, first spotted in London in 2006, and then progressively further north, as climate change expands its comfort zone to progressively more northern latitudes. Sun journalists must have bookmarked the Forestry Commission website, as each new update provoked another of the articles listed above.

In summary, Dr. Tew’s report had virtually zero impact on British public consciousness.

This isn’t because British people don’t care about trees. Even amid headlines dominated by the Middle East, Ukraine and political scandals, the same publications have devoted yards of column space over vandals felling a single photogenic sycamore tree in a gap of Hadrian’s Wall. There are plenty of petitions to save single iconic trees.

This suggests that British people care deeply about trees, or more precisely, that the most influential British media editors reckon they’ll care deeply about one particular tree.

Despite its relative baldness, the UK still has around 3 billion trees.

Logically, a report about 100% of all British trees over the next 50 years should be around 3 billion times as newsworthy as the ‘iconic Sycamore Gap Tree’.

Why the disparity? We refer you to the start of this article.

What expert warnings were ignored?

So what was behind that solitary Guardian article, and absent from most of the rest of the British media?

We do urge you to break the mould and read Dr. Tew’s report yourself – the report is only about three times the length of this article, and you can skip any bits you find boring. It’s well-written and signposted. Not too much jargon, plenty of helpful diagrams – like their Top 15 graphic shown above.

The top 3 of their top 15 issues facing Britain’s trees were:

- Catastrophic forest ecosystem collapse

- Increased drought and flooding change the social costs and benefits of trees

- Forest management becomes more challenging due to changing seasonal working windows

If you’re curious about the other 12, do read the report, but we can reveal a theme you may have spotted:

nearly every single issue is related, to some degree or other, to climate change.

Increasingly severe weather events, more invasive species, greater threat to biodiversity, funding, product diversity and supply continuity… There’s hardly a single threat that isn’t made worse by global heating, caused by our addiction to fossil fuel.

This is true of all human activity and intervention, but as we mentioned at the top of this article, trees are particularly important because they take ages to grow. Trees are both:

- Canaries in the coal mine, warning of imminent catastrophe if we choose to listen

- Epic carbon sequesterers, capable of mitigating the worst, if we choose to act

Farmers planting annual crops can adapt their planting from year to year, adapting to climate change in ‘real time’.

Foresters can’t. Traditionally, woodlanders planted and nurtured trees in the knowlege that neither they, nor their children, would reap the reward. Good stewardship through generations might mean it could provide a living for their grandchildren.

As the 46 tree experts put it:

As the forest management sector naturally operates over long timescales, the importance of using good foresight is self-evident

These and many of the other issues are large scale, with far-reaching implications. We must be careful to avoid inaction through being overwhelmed, or indeed to merely focus on ‘easy wins’ without considering broader ramifications.

The 15 horizon scan issues presented here are a starting point on which to build further research, prompt debate and action, and develop evidence-based policy and practice.

Solutions, not just problems

The Forestry Commission paid these experts to itemise and rank the problems. Their ‘horizon scan’ comprehensively does that.

But they didn’t stick to the Commission’s narrow problem-stating brief.

Like the rest of us when presented with a major problem, they want to know what we should do. They want solutions, not just problems.

Because trees take decades to grow, and we have no idea what the climate will be like in 10 years, let alone 50 or 100, we need to do something now.

This is a universal dilemma that goes way beyond British woodlands:

- The negative consequences of inaction are certain and predictable

- The positive consequences of active, pre-emptive intervention are less worse

Even if what we do carries its own risk, we now need to identify, quantify, assess, and offset those possible risks against the humongous, 100% guaranteed risk of inaction.

This urgency applies not just to trees, and not just to Britain, and is universal. All of us – trees, humans and the rest of life on Earth – are made of carbon, after all.

The Forestry Commission authors, like the IPCC scientists and other experts who spend their lives examining facts and applying the scientific method, are humans too. They’re not just experts who care deeply about trees, they’re also mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, who care deeply about our legacy, human civilization and our planet.

So despite the academic language, the authors honk, very loudly and urgently, our need to come up very rapidly with solutions. In their words:

We hope that this stimulates greater recognition of how our forests and sector may need to change to be fit for the future. In some cases, these changes will need to be fundamental and momentous.

Solutions remain elusive.

A Fundamental, Momentous Solution

Here’s a solution, an immediate action we could collectively agree to take.

A word of warning – you probably won’t like it, for one or more of the following reasons:

- it runs counter to what we’re used to thinking of as common sense

- It contradicts a Native Good. Non-Native Bad mantra we’ve absorbed for generations

- Sun headline writers will have a field day linking it to their xenophobic obsession

- You may prefer solutions that may be less effective, but appear more ‘achievable’

None of which means it’s not our best current option from a range of bad options, the worst of which is Do Nothing. Our history of Doing Nothing means we ran out of unambiguously Good options decades ago.

So what should we all do, now, as the least-worst option for us, our trees, our civilization and our planet? We propose:

Safely Plant More Diverse Species in New Woodlands Now

Underwhelmed? At 9 words, it only just fits on a placard. Protestors would need a deep breath before attempting to chant it, but all the extra words are necessary to convey the nuances and complexities that are inevitable when dealing with somethine as complex as adapting to climate change. Each word carries one such nuance:

- Safely: introducing non-native species will require elevated vigilance against importing pathogens. See Dutch saplings and sweet chestnut mentioned above

- Plant: trees take ages to grow, as we may have mentioned. For a better future, we need to plant seeds or saplings now

- More: 13% tree cover is nowhere near enough for the UK. Come to that, 31% probably isn’t ‘enough’ for the global average.

- Diverse Species: short, restrictive lists of approved native species served us well in the past, but in a past when we could confidently predict the average temperature in 100 years time would be much the same as it is today. We can no longer confidently predict what the average temperature will be in 10 years time. This means we need to test now how different tree species from a range of degrees south for northern hemisphere countries like Britain (and degrees north for southern hemisphere countries) adapt to new habitats. To be crystal clear, this means expanding the list of approved species to include non-native, ‘exotic’ or ‘foreign’ species. Functionally, they all mean the same thing, though you can guess which adjectives Sun subeditors will choose. The point is that they’ve proved themselves adapted to hotter temperatures

- New Woodlands: not ancient woodlands, or mature woodlands. They have the capacity to adapt over time through ‘rewilding’. We’re talking about the monocultural plantations that currently exist, which form the majority of British woodlands, and the future plantations that need to exist as soon as possible

- Now: this is the key part. We can’t dither any longer

Apologies for the 9-word mouthful – we should probably add a couple more caveats. Any legislation mandating this would need to be made up of yards of Tightly-Worded Legal Clauses (AKA ‘Twollocks’) to close loopholes and prevent bad actors from gaming the new system.

The problem is, the longer the slogan, the more complex the message, the less impact it’s likely to have. Just look at the Sun headlines about moth invasions and the devastating report compiled by the Forestry Commission’s 46 experts.

Just Stop Oil is pithier, but it addresses our current problem, not a future solution.

***

See Through News has a project designed to make this call to action a reality.

For more on how we’re leveraging Ben Law’s Woodland Year to measurably reduce carbon, subscribe to the See Through News newsletter (free to your inbox every Sunday) or our YouTube Channel.