A comedian’s article on electric vehicles holds some important lessons about our fossil fuel problem, though maybe not the ones you think

First Gear: Mr. Bean’s EV article

Rowan Atkinson, a masterful comedian best known globally for his imbecilic comic persona Mr. Bean, recently published an opinion piece on the topic of Electric Vehicles (EVs). It appeared in The Guardian, under the headline:

I love electric vehicles – and was an early adopter. But increasingly I feel duped

First, Atkinson stakes his credentials. He’s known for being a lifelong car nut, but also:

- has an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering

- a Masters in control systems

- bought his first hybrid 18 years ago

- bought his first 100% electric car 9 years ago

So not an environmental expert, but neither is he a celebrity mug.

At 1,300 words, the comment piece had space to explore a complex issue in more detail than a standard 800-word news article. By and large, it did, presenting a range of factors, with nuanced pros and cons, quoting statistics and containing links to supporting evidence.

Atkinson’s tone was considered, almost academic. It was elegantly written without containing any overt gags. There were no gratuitously snide comments. Assertions were rare, and most observations were couched in caveats, typified by his concluding paragraph:

Friends with an environmental conscience often ask me, as a car person, whether they should buy an electric car. I tend to say that if their car is an old diesel and they do a lot of city centre motoring, they should consider a change. But otherwise, hold fire for now. Electric propulsion will be of real, global environmental benefit one day, but that day has yet to dawn.

‘Often’, ‘tend to’, ‘if’, ‘a lot’, ‘consider’, ‘for now’, and ‘one day’ . These are not the tools of a troll or a fanatic.

So not a car crash article at all. Yet.

Second Gear: in-house comments

First dibs on public response went to Guardian readers, under the watchful eye of the newspaper’s online moderators.

As might be expected of a celebrity article on as contentious an issue as electric vehicles, ‘Mr. Bean’s electric car article’ attracted plenty of comment. More than 1,500, in fact, before they closed shop.

‘Below-the-line’ reaction echoed the article’s careful and diffident tone. Guardian readers, at least those the moderators greenlit to publish their comments, especially those featured at the top of the list, generally followed Atkinson’s attenuated, balanced tone. Some typical comments:

- I think that Roman [sic] Atkinson’s views on this matter are essentially correct and well-informed, but taking a wider picture…

- The article seems a bit behind the curve.

- leave Mr Ban [sic] behind and turn to writing. This is one of the best articles I have read on the Guardian. really well written

Most of the comments picked up on a single point, expressing moderate, qualified support or criticism of Atkinson’s positions on the electric vehicle debate. Many were more comprehensive point-by-point critiques, full of facts and references, often running to several hundred words, mini-articles in themselves.

At this point, The Guardian could have been feeling pretty pleased with itself. A well-known byline guarantees eyeballs, but favouring celebrity stars over professional journalists is risky too.

Superstars might not be as fastidious about facts, or as well-informed, as a professional journalist. They may not respond well to being fact-checked for an opinion piece. Even if they know their stuff, newspaper running celebrity pieces invite accusations of trivialising serious subjects.

Still, if this was clickbait, it was classy clickbait. So far so good.

Then the article escaped into the wild. Once at large, it veered increasingly out of control following the spiralling course of a Mr. Bean episode.

Third Gear: corrections

Understandably, newspapers dislike printing corrections.

Professional pride creates a natural resistance to admitting mistakes. Printed corrections usually only appear as a result of, or to dodge, legal action. They tend to be printed as late as possible, in as small a font as possible, as distant as possible in time and space from the original offending text.

The Guardian is much better than most at fessing up. Maybe because it’s the only major British newspaper not owned by billionaires, it may be more driven by objective journalistic instincts than raw might-is-right bluster, and less subject to second guessing the wishes of some Murdoch-like proprietor.

Maybe it’s more cynical. The Guardian’s marketing team could have focus-grouped its corrections policy, and concluded that a modicum of public acknowledgement of errors plays well. The data may have proved that a bit of humility suggests trustworthiness, and integrity, and sells more papers.

Or maybe its journalists feel contrite about berating public figures for not admitting mistakes, and not practising what they preach. Such hypocrisy doesn’t bother most UK national news titles, who cheerfully emulate the modern politician’s penchant for doubling-down on untruths, rather than correcting them.

Whatever the paper’s reasons, The Guardian published the following correction two days after publication of Atkinson’s electric vehicle opinion piece:

This article was amended on 5 June 2023 to describe lithium-ion batteries as lasting “upwards of 10 years”, rather than “about 10 years”; and to clarify that the figures released by Volvo claimed that greenhouse gas emissions during production of an electric car are “nearly 70% higher”, not “70% higher”. It was further amended on 7 June 2023 to remove an incorrect reference to the production of lithium-ion batteries needing “many rare earth metals”; to clarify that a reference to “trucks” should instead have been to “heavy trucks for long distance haulage”; and to more accurately refer to the use of such batteries in these trucks as being a “concern”, due to weight issues, rather than a “non-starter”.

These were the kind of errors of fact, or omission, that many of the critical readers comments had pointed out.

Their degree of outrage felt about the fact that these verifiable errors were printed in the first place largely reflected whether they broadly supported the notion of Electric Vehicles or not. Even Guardian readers were divided on the subject.

This division signalled a revving up of ‘the debate’. Or more accurately, its predictable acceleration from nuanced debate into polarised name-calling.

Overdrive: The Twittersphere

Released onto Twitter’s featureless, sprawling test track, Atkinson’s article went into overdrive. Electric vehicles are a classic online wind-up, almost as effective as cyclists. This electric vehicle article quickly became another peg on which to hang your Pro-Car or Anti-Car colours, and abuse the opposition.

Viewed through the binary goggles of knee-jerk social media platforms, any attempt at balance went up in smoke. Nuance evaporated. Caveats were blown away.

The Newspaper

The role of the Guardian sub editors now comes into focus. Having to correct an article two days after publication is proof of their negligence. Opinion pieces must still be based on evidence. Sub editors should have fact-checked Atkinson’s copy more diligently for its more obvious clangers. Two in particular are known to be, enthusiastically propagated by the auto industry when promoting electric vehicles, but implausible on close inspection.

Take hydrogen as an alternative fuel. More than a decade ago, Toyota took a massive strategic gamble on hydrogen-fuelled cars, now widely acknowledged to have been disastrous. The carmaker’s face-saving headlines may now proclaim its new boss still publicly insists hydrogen has a future, but further down the press release he’s telling Toyota’s engineers to crash into reverse, and go full throttle to make up their lost Electric Vehicle ground.

More diligent fact-checkers would have gently pointed out to Atkinson that as Toyota’s huge strategic error has become more obvious, its stock price has fallen off a cliff. Best not to drive any further down that dead-end.

They could also have avoided the embarrassment of a correction by challenging Atkinson’s naive hope that ‘synthetic’ fuels might prolong the life of the internal combustion engine, and stave off the rise of the electric vehicle. Biofuel has long been proved to be illusory, requiring far more energy, and gobbling up far too much valuable arable land, to be practical.

Whether their fact-checking oversights were careless or cynical matters less than the headline the Guardian sub editors chose. This is where the true, subtler, lessons of this opinion piece may lie.

Few Twitter warriors, on either side, take the time to read long articles. That would risk tempering their outrage, or diminishing the passion with which they declare their bipartisan allegiance. No fun at all.

Instead, they glance at the headline, trigger their Pro or Anti reflexes, and pile on. Their opinions on the topic of electric vehicles are fixed. They neither go to social media to challenge them, nor do our Silicon Valley Overlords benefit from challenging their electric vehicle stances.

How ingenious, or cynical were the Guardian sub editors when they decided to go with their ‘duped by Electric Vehicles’ angle? They must have known this would be red meat for both sides of the debate.

The ‘debate’

The fact that Atkinson’s article was relatively nuanced for a mainstream media opinion piece says more about the informed quality of the ‘debate’ than it does about his expertise.

More detail and nuance doesn’t necessarily demand more word-count. It just requires you to care more, spend more time working out how to explain the many variables, and come up with creative solutions.

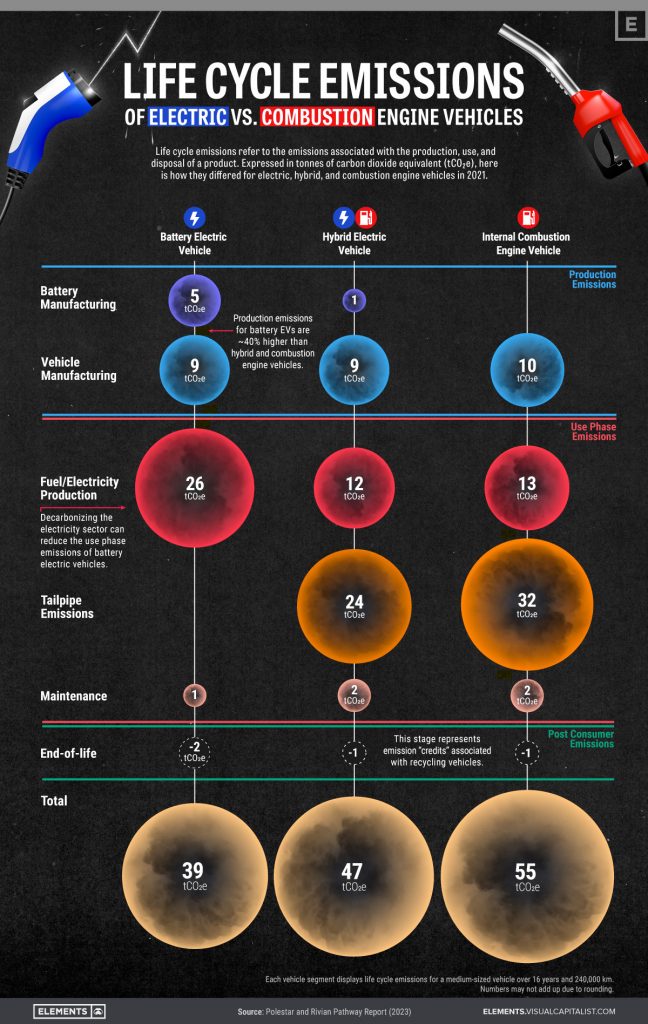

Here’s an example of how this can be done, a graphic analysis of the lifetime emissions of Electric Vehicles, Hybrids, and internal combustion cars crafted by Visual Capitalist.

Which debate?

Even more important point than debate detail, is which debate we choose to debate. Atkinson’s article is entirely framed by the assumption that our future features cars, and lots of them.

The debate is framed as electric vehicles v. gas guzzlers, not cars v. fewer cars. Atkinson makes no mention of ramping up provision of public transport alternatives, and alludes only briefly to reducing demand. Even so, headlines could have been cherry-picked from these sentences:

- Increasingly, I’m feeling that our honeymoon with electric cars is coming to an end, and that’s no bad thing: we’re realising that a wider range of options need to be explored if we’re going to properly address the very serious environmental problems that our use of the motor car has created.

- The biggest problem we need to address in society’s relationship with the car is the “fast fashion” sales culture that has been the commercial template of the car industry for decades.

- Fairly obviously, we could use them less.

They could just as well have gone with a headlines like:

- Age of ‘Fast Fashion’ cars is over

- We need to use cars less

But they didn’t.

EV Lessons for Carbon Drawdown

For what they’re worth, here are our nuanced observations about the role of electric vehicles in rapid carbon drawdown.

- The car industry only reluctantly embraced Electric Vehicles as their least-worst response to climate change, but are now (Toyota apart) gung-ho about them. If they can re-tool rapidly enough, there’s little downside. If they get ahead of the competition, like China’s EV manufacturers have, there’s plenty of upside too.

- Car companies are in the business of selling cars, not their fuel source. If electric vehicles mean we buy more new cars faster, that’s great for business. Unless government regulation forces them to, they’re indifferent to the carbon cost of switching to EVs. Their shareholders care about them selling more units, not fewer.

- Currently, the embedded energy costs, or unsustainable demand for raw materials, are not factored into their share prices, because our governments aren’t insisting that they should be.

- What growth-obsessed car makers and governments are not focused on is reducing demand, the only sustainable future.

- For all its apparently even-handed examination of current supply-side options, Atkinson’s article, and most of the transport debate, lacks a focus on improved public transport, and fewer journeys.

Storytelling Lessons for Carbon Drawdown

So what has Mr. Bean’s contribution to the electric vehicle debate taught us about effective climate action?

Fact-checking is important, but not as important as framing the debate:

- The more nuance you can introduce, the better.

- However much nuance you introduce, social media will ignore it.

- Once any ‘debate’ gets stuck in binary Pro and Anti ruts, it’s unlikely to change any minds.

We wish the lessons were easier to implement, but their complexity reflects the nature of the problem.

Facts, science, objective truth and evidence are not enough, on their own, to change minds. If they were, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in.

Effective climate action also requires a recognition that we’re driven by emotion, and are resistant to change. Learn from Big Oil and their public relations experts – they get it, and exploit this foible to great effect, as least for their bottom lines and short-term share valuations.

Until we can find a way to get our governments to oblige them to change through regulations, and to enforce them, urgent carbon drawdown will always be a future hope, rather than current reality.

So let’s focus on changing government regulation, not our cars.