Technology alone can’t ‘save the planet’ – just consider the QWERTY keyboard’s longevity

What does Chinese ingenuity in avoiding technological disaster teach us about how humanity can avoid ecological Armageddon?

QWERTY’s Threat to Chinese Communism

By the 1980s, Beijing-based revolutionaries were getting very concerned indeed about a revolution starting up in Silicon Valley.

Chinese Communist Party technocrats, observing the Digital Revolution, foresaw an existential threat that China would be powerless to resist. This threat had nothing to do with capitalism vs communism, and everything to do with QWERTY vs characters.

China’s hopes of keeping up with the West, they feared, might be sabotaged not by the distribution of capital, but by the impression of capitals (and lower-case letters) via a keyboard.

The keyboard in question was the ubiquitous ‘QWERTY’ layout keyboard, named after the top-left 6 keys on the standard keyboard layout. Whatever its economic and political model, QWERTY threatened China’s long-term competitiveness and security.

Officials who understood such matters, and the scientists and inventors they oversaw, were terrified that China was doomed to be left behind by the Age of Computing, because their language takes ages to type.

Conventional wisdom at the time gave Chinese patriots reason to gloat when it came to reading. The nature of Chinese characters (technically ‘logographs’) compresses lots of meaning into a single square-ish space.

Logic suggests this makes Chinese faster to read than alphabetic languages, which require the decoding of a string of letters in order to derive the same meaning. Subsequent research has cast doubt on this, but they didn’t know that at the time.

Chinese technocrats were painfully aware, however, of Chinese’s disadvantage when it came to writing, or specifically data input on a computer.

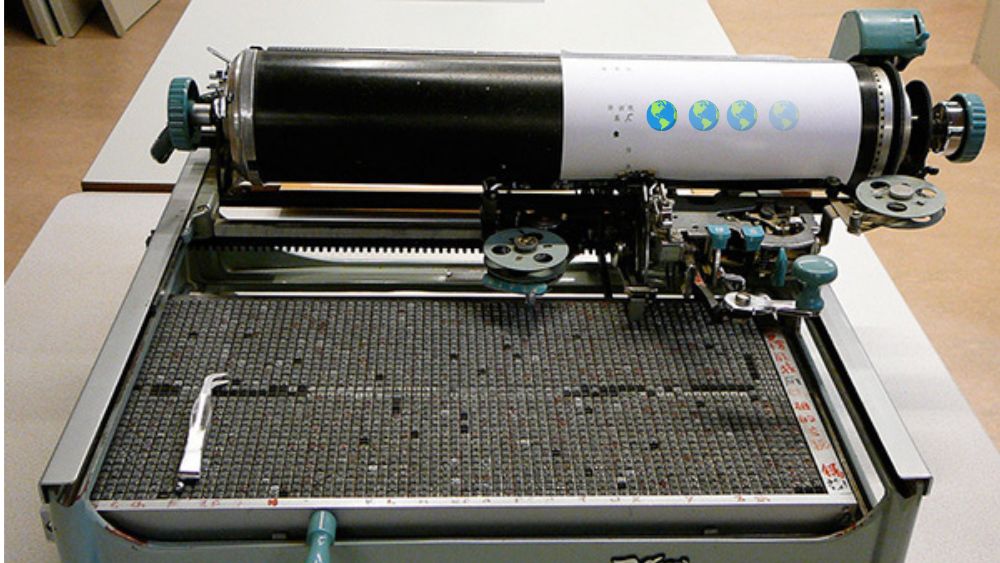

The input problem was obvious to anyone who’d seen a Chinese typewriter.

By the 80s, Even the most sophisticated Chinese typewriters were huge, unwieldy and hard to operate. Expert operators of the state-of-the-art Double Pigeon model could generate a maximum of around 20 characters a minute.

Characters aren’t exactly the same as words, but are roughly analogous. Chinese technocrats knew that in the alphabetically-inclined West in general, and in Silicon Valley in particular, average typists could hammer out 40 words per minute, and skilled typists could comfortably exceed 100.

In a computer-dependent future, the fundamental nature of Chinese characters suddenly loomed as an insuperably huge handicap. China’s exquisite writing system, as much art as function, no longer looked like a sublime expression of thousands of years of culture, but as a fatal flaw in its DNA that threatened a long, slow death.

The Typing Rebellion

What happened next has been documented in detail by technology historian Thomas Mullaney in ‘The Chinese Computer: a Global History of the Information Age’.

It’s a fascinating story. The short version is that the combined efforts of thousands of Chinese engineers, linguists, programmers and designers started to pay off by the turn of the millennium.

Imaginative workarounds used the QWERTY keyboard to crack the Input Method Editor (IME) challenge. When combined with advances in autocompletion, these incremental advances first narrowed the Chinese data entry gap, and in some respects may now have leapfrogged their QWERTY competition.

In 2013, in a hall in Henan province, student Huang Zhenyu won the National Chinese Characters Typing Competition by rat-tat-tatting 222 characters in 60 seconds.

This approximates to around 200 English words per minute. There’s no exact correlation between Chinese characters and English words, but Huang’s feat is unquestionably on a par with Stella Pajunas’ English world record of 216, set in 1946.

The remarkable thing is that Huang used the same QWERTY keyboard layout Pajunas used 66 years before.

Thirty years after Chinese technocrats feared QWERTY would be the West’s secret weapon to defeat China, Huang demonstrated it could be used to at least equal, if not surpass its would-be annihilators.

What do the tool and the means of China’s typing revolution teach us about tackling humanity’s current existential crisis?

This article examines what the QWERTY keyboard’s remarkable longevity, and understanding the difference between striking one of its keys and seeing the result on a screen, can teach us about mitigating the worst impacts of human-induced climate change.

QWERTY’s stubborn resilience

By 1874, when Samuel Clemens bought his first typewriter, he was already writing under his pen name Mark Twain.

A year later he hand-wrote a letter to the Remington Company complaining their typewriter ‘corrupts his morals because it makes him want to swear’. A year later, Twain delivers his masterpiece Tom Sawyer to his publishers as a literal manuscript, written by hand, using a pen.

Within 7 years, however, they received Twain’s Life on the Mississippi in typescript. This has become known as the ‘world’s first typewritten novel’, even though it’s not a novel, and Twain probably dictated it from a handwritten draft.

Nonetheless, Life on the Mississippi marked the beginning of the end of the pen’s ascendency over the quill, establishing the QWERTY hegemony that persists today.

There’s no evidence Remington’s QWERTY layout was specifically designed to slow down typing speeds to stop the mechanical keys jamming, but we do know that QWERTY was just one of many competing keyboard layouts being patented around the Civil War period.

Many more designs have been invented since. Stenotypes, used in courtrooms, can produce in excess of 350 words per minute. Designers from Dvorak to Colemak have claimed their layouts boast greater ergonomic efficiency and faster speeds.

None has caught on.

Why not? How come we’re still using the same basic tech design 150 years after it was patented?

Few inventions have survived unchanged over the past century and a half. QWERTY has thrived throughout the arrival of radio, TV and the Internet, despite being demonstrably sub-optimal.

Even more remarkably, QWERTY has survived voice-to-text technology specifically designed to replace it.

Voice-to-text has almost as long a history of being a ‘nearly there’ technology as nuclear fusion. For generations, proponents have touted it as the next great breakthrough. For generations, the breakthrough has always been just over the horizon.

Voice recognition has made huge leaps since 1952, when Bell Labs demonstrated ‘Audrey’, able to automatically print out spoken digits, so long as they were spoken clearly and slowly enough.

Today, Siri and Alexa replicate the kind of quotidian talking-to-computer tasks that were science fiction a generation ago.

Yet QWERTY, whether on physical keyboards in offices, or on mobile phone touch screens, remains our dominant form of data entry, with no immediate prospect of being displaced.

There are many explanations for QWERTY’s longevity, but there’s one that’s invisible to any Western observer, but obvious to any Chinese.

Depression and Impression

Extend your left hand pinky finger, depress the ‘Q’ key. A ‘q’ appears on the screen.

For the alphabet tribe, these two events appear to be one and the same. Researchers in this field have a pithy phrase for this concept – ‘depression equals impression’.

But a moment’s thought reveals this as an illusion.

Look at the first sentence of this section. The typewriter key is labelled ‘Q’, whereas what appears, unmediated by the Shift key, is a lower-case ‘q’. But there’s more.

Imagine a prankster swapping around the labels on the keys, and the illusion is further exposed. The correlation between depressing the key marked ‘Q’ and any given character appearing on your screen turns out to be rather more complex than it may appear to the alphabetically-inclined.

The depression-to-impression process is actually mediated by a whole string of assumptions. These assumption appear so obvious to the alphabet-accustomed that they’re blinded to the fact that ‘depression’ of the key is not directly linked to the ‘impression’ on the screen at all.

This illusion was always obvious to the generations of Chinese techno-linguists, as they struggled to make the ubiquitous QWERTY keyboard compatible with the entry of Chinese characters.

After the end of the American Civil War reduced demand for their guns, the Remington company started looking for new products. As well as sewing machines, they saw a future in newfangled typewriters.

They bought the QWERTY layout from Christopher Sholes, from Milwaukee, and started marketing it as a modern replacement for the pen.

The late 19th century was a great time to re-examine, and re-invent, old input/output standards, on both sides of the Atlantic.

In 1882, Hungarian pianist-engineer Paul von Jankó patented his mosaic-like piano keyboard, with 6 rows of keys. Like different typewriter layouts producing the same text, the Jankó keyboard produced the same notes, but via a different input mechanism.

Remington’s QWERTY and Jankó’s mosaic both addressed old input problems in new ways. They were technological solutions, one producing words better than a pen, the other generating musical notes better than a standard piano keyboard.

Half a century later, in an innovation more akin to that taken by the Chinese techno-linguists, American composer John Cage took the standard piano input technology, and used it to create different outputs.

Cage’s his ‘prepared keyboard’ compositions involved inserting bolts, screws, mutes and rubber erasers on or between the strings to extend the sonic range generated by a standard piano keyboard.

Another half-century on, and a division emerged between video games players who preferred to play using consoles or standard PC keyboards. In this case, the output in the outcome of the games was identical, and only the input method differed.

Remington, Jankó, Cage and arcade video game pioneers may not have known it, but they were all dabbling in hypermediation.

Hypermediation – you heard it here first

If you’re unfamiliar with the term ‘hypermediation’, you may soon start to hear it in contentious culture-war contexts, like academic papers on The Theory of Hypermediation: Anti-Gender Christian Groups and Digital Religion.

For our purposes, we need only consider its technical definition. One scholar has defined hypermediation as:

‘A complex network of production, exchange and consumption of processes that take place in an environment characterised by countless social actors-agents, digital media and technological languages’.

In the context of the keyboard wars, hypermediation is relatively straightforward. Simply put, Q does not necessarily equal Q.

For Chinese people using QWERTY keyboards, pressing the key marked ‘Q’ could be the start of a series of prompts and automations to generate a character that starts with ‘q’ if spelt using the pinyin Romanisation system.

For example, the ‘qi’ in tai qi (usually rendered in English, in an older Romanisation system, as ‘Tai Chi’) would start with hitting the ‘Q’ key.

Seen through Chinese eyes, the QWERTY keyboard is just a tool in a toolbox, a chain in a link, a cog in a machine. Ironically, this is more akin to how the original keyboard innovators saw a keyboard, as a pen-replacement tool for the blind.

When used to write Chinese, a QWERTY keyboard is simply a means to the end of invoking or retrieving Chinese characters. Different Input Method Entry (IME) processes may use the keyboard in different ways, but all deploy QWERTY as an intermediary tool in this particular ‘complex network of production’.

For decades, ingenious Chinese pragmatists have tinkered with the incorporation of QWERTY with other tools, from predictive text to AI. Their remarkable success in enabling student Huang to rival the fastest ‘native’ users of QWERTY keyboards has left Western technologists viewing this standard item of office furniture in a new light. They’re now wondering what they can learn from Chinese computational concepts, in particular hypermediation.

Chinese probably shrug their shoulders at this. China has been the world’s technological leader for most of human civilization. After a rough couple of centuries, they may just see China’s pragmatic technological innovation reverting to its historical world-leading norm.

Thinking in a longer timescale can be instructive.

Like with understanding climate science…

QWERTY’s climate action lessons

So what lessons do QWERTY’s quirky history hold for climate action?

Path Dependency

QWERTY’s longevity has long fascinated economists. They see the keyboard design as a classic example of path dependency, defined by Investopedia as:

The continued use of a product or practice based on historical preference or use. A company may persist in the use of a product or practice even if newer, more efficient alternatives are available. Path dependency occurs because it is often easier or more cost-effective to continue along an already set path than to create an entirely new one.

Investopedia’s definitive example of path dependency?

‘The use of fossile fuels as primary energy sources persists, in part, because a multitude of tertiary industries is intrinsically tied to fossil fuel use’.

Hypermediation

In 1997, the board of Exxon gathered for a meeting that had far more dramatic consequences than the fate of one particular oil company.

Essentially, it hinged on hypermediation, i.e. distinguishing between a thing and the representation of the thing.

The board had just received a top-secret, comprehensive, and, it turned out, remarkably accurate, report from their in-house science unit. It clearly laid out, based on the most advanced models at the time, the devastating climate consequences of continuing to drill for oil.

The Exxon board did not dismiss the report out of hand. As is now well documented, Exxon’s bosses carefully considered the binary path ahead of them, and then dismissed it out of hand.

The report framed a classic hypermediation challenge:

- Keep bashing the Q key in order to generate a ‘q’ on screen, i.e. see Exxon as an oil company and nothing else.

- See the Q key as part of a series of decisions that resulted in generating shareholder value, i.e. see Exxon as an energy company that could just as well invest in renewables as fossil fuel extraction, should they be concerned about their business’s impact on human civilisation and the ecosystem that sustained our evolution.

Exxon rejected hypermediation, shut down their science unit, and successfully suppressed the report for decades. They, and other oil and gas companies, continue to bash the Q key to this very day.

This is not just a historic problem. The advent of AI has made the debate public, rather than confined to a boardroom, but so far this seems to have made little difference to outcome. We’re all the Exxon board now, and face a similar crossroads:

- We continue to see AI, unmediated, as the latest technological gold-mine, a new way of maximising shareholder value, and ignore its insatiable power consumption. Input: money. Output: money.

- We see AI in its hypermediated role, as a tool to be prudently deployed in service of the more urgent and important output of rapid decarbonisation. Input: money. Output: carbon reduction.

All indications so far are that we’re giving the green light to out Silicon Vally Overlords, so feared by the Chinese Communist Party technocrats in the 1980s, to go for Option 1.

They’ll continue to bash the Q key like lab rats addicted to cocaine-laced treats.

QWERTY inspiration

We can now choose to see ourselves like the Chinese technocrats in the 1980s, terrified of an existential threat we were powerless to resist.

Or, like them, we can re-frame the threat as part of the solution.

Just as Chinese technolinguists re-imagined the QWERTY keyboard as a threat, and started conceiving of it as a tool to a different end, we can stop seeing technology as a means to generate profit, and start using it as a tool for decarbonisation.

Or we can keep on bashing the Q key until the oil runs out.